“Protecting and enhancing members’ pensions and benefits has been Job Number One for NJEA since 1896.” —NJEA President Joyce Powell, June 2006

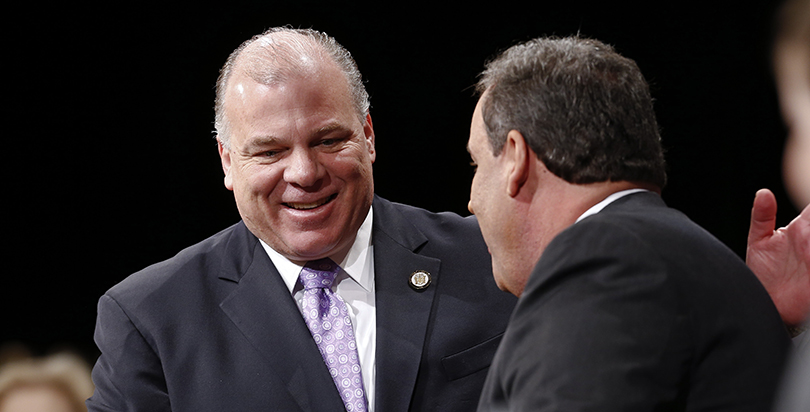

For more than two decades, the New Jersey Education Association has lived up to Powell’s words. State senate president and ex–gubernatorial hopeful Steve Sweeney can tell you all about it.

New Jersey has a severe pension crisis. Under new accounting standards, the state’s unfunded pension liabilities are $95 billion. Its retiree health care obligations add an additional $65 billion, for a total of $160 billion. (This doesn’t include yet another $40 billion for local government pensions.) The entire state budget is $35 billion.

It simply doesn’t have the money to pay for its pensions.

Yet last year NJEA hoped to pass a constitutional amendment that would lock this bankrupt system into the state constitution regardless of budget-busting consequences. Senator Sweeney refused. The NJEA vowed revenge, and got it.

How did we get to this extreme?

The shortfall in state funding of pensions is a direct consequence of NJEA’s enormous political power. As then-president Michael Johnson said in 1998: “Our excellent pension system [is] the result of hard-fought legislation and politics.” All aspects of public pensions are determined by political decisions. And NJEA is the dominant political power in the state.

The union is New Jersey’s top political spender by far, but that doesn’t capture the magnitude of its political influence — which can also be measured in the thousands of volunteers who staff campaigns in every district; in the UniServ program, a statewide cadre of political professionals that helps local unions get out the vote; and in the effectiveness of NJEA’s Communications and Government Relations divisions, which are integral to shaping and messaging its political agenda.

Lastly, reported political spending does not account for the annual Pride in Public Education campaign, a seemingly benign statewide PR effort to give schools a positive image in their local communities that actually organizes to ensure “yes” votes in school budget elections even when it may hurt the district.

From 1995 to 2015, NJEA spent $756 million on political influence–building, a clearer reflection of NJEA’s real-life influence.

With that kind of money, NJEA generally got what it wanted on pensions.

In the early 1990s, after Democrats crossed the union by shifting pensions to local school districts — where resistance to raising property taxes, which fund schools, might constrain increases in teacher salaries and pensions — NJEA endorsed 46 Republicans and 3 Democrats in state elections and was credited with flipping the legislature to the GOP. Neither the Democrats nor the Republicans forgot.

Predictably, legislation that enhanced pension benefits went on to pass with strong bipartisan majorities. In 1997, NJEA was successful in gaining the “non-forfeitable right” to pensions for its members, which meant that 89 percent of today’s teachers are protected from any reduction — vastly complicating future reform efforts (including Governor Chris Christie’s 2010 and 2011 reforms, which mostly affected new teachers).

In 2001, the legislature passed a 9 percent pension increase. Even though pension fund assets were billions lower after the dot-com bust, only one legislator dissented. NJEA called the proposal — which amounted to a raid on the pension fund —“one of the most significant legislative accomplishments in NJEA history.”

Crucially, NJEA kept teacher salaries negotiated at the local level while the pension payouts based on those salaries were negotiated with the state; rising pension costs would otherwise squeeze local education budgets or require higher property taxes.

At the state level, NJEA pushed freely for enhanced pensions and benefits. Governor Christie maintained that the average teacher contributes $195,000 over a 30-year career and gets back $2.6 million in benefits. The state’s 2005 Benefits Review Task Force reached a similar conclusion.

But lawmakers, eager to please NJEA and keep taxes down, sweetened pensions without paying for them. The union could have used its clout to press the legislature to fund the improved benefits, but instead it has worsened the problem — using its political force only when increased benefits have been threatened. Throughout the period that pensions were being short-changed, both NJEA-endorsed candidates and incumbents who back the current system were elected at very high rates.

These years of strong-arming the legislature provide historical context for the union’s effort, in 2016, to stick taxpayers with the $95 billion pension shortfall by enshrining the bankrupt system in the constitution. After Sweeney refused to support NJEA’s amendment, the union pledged to support his potential opponents in the 2017 Democratic gubernatorial primary. In October, he surprised the state’s political world by withdrawing from the race.

With Sweeney gone, NJEA will now be able to elect a politician who will do its bidding, perfectly encapsulating the root cause of New Jersey’s pension crisis.

Mike Lilley is an adjunct scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and former executive director of Better Education for New Jersey Kids.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)