Once Largely Ignored, New Orleans Special Ed Students Find Meaning and Skills After High School

New Orleans, Louisiana

In keeping with the coffee shop’s motto — “We just want to warm you up” — the visitors had been welcomed at the front door. Per their orders, each had been served a steaming cuppa joe.

The wrinkle Toasty’s front-line customer service team hadn’t seen coming: One of their guests wanted to pay for both drinks. Stymied, the kitchen manager and cashier turned to teacher Megan Gold for help.

Welcome to Opportunities Academy, a new kind of special education program developed by one of New Orleans’s most successful network of schools. The idea: To give high school graduates with moderate to severe disabilities up to four more years of school, and to make the experience as much like college as possible.

If you know anything about the history of special education in New Orleans schools, you’re likely incredulous that the city’s most fragile students are enrolled in a program that could serve as a model for helping students with disabilities create meaningful lives.

By law, students with disabilities are entitled to an education until their 22nd birthday. Research and federal policy both recognize that for these students self-determination skills are closely tied to academic achievement and beyond: to the likelihood that life after high school will be fulfilling. Students’ hopes and preferences are supposed to be the centerpiece of what is at least in theory a highly individualized process.

But transition services for these special needs students — the programming intended to bridge the gap between high school and adulthood — are notoriously weak in many school districts. Programs are scarce and underfunded. Frequently those that do exist are neither individualized nor coordinated. Students and their parents are supposed to be full members of the special education planning team, but impoverished families and families of color face huge cultural hurdles.

The problems are compounded in New Orleans, which has both a history of abysmal special education and a scarcity of the social services young people with disabilities turn to when schools don’t deliver. Opportunities Academy is part of a sweeping effort to change this, piloting strategies schools throughout this city — and perhaps others — may adopt.

Opportunities Academy started out in Sci Academy, one of New Orleans’s most successful open-enrollment schools. (The city’s highest-performing schools can select their students, who are, by definition, mostly wealthy.) It’s one of three schools operated by Collegiate Academies, and it was also tapped to develop model high school programs for students with moderate to severe needs and those with unmet mental health needs.

Teacher Megan Gold asked to work in special education shortly after she started at Collegiate in an AmeriCorps position. The schools hired her the next year as a paraprofessional to provide behavioral support and small-group instruction. When Collegiate started its transitions program for special education students, Gold was asked to take it over.

Virtually all of Collegiate’s students are impoverished minorities, yet their achievement outpaces New Orleans’s and state averages. Some 98 percent of graduates are accepted into college; 85 percent are the first in their family to go to college. About 20 percent of them receive special education services. Two years ago an eye-popping 72 percent of special ed students graduated, double the statewide rate.

(Technically, students in special education transition programs like Opportunities Academy simply stay enrolled in high school without graduating; Collegiate’s official special education graduation rate has actually fallen since the program opened.)

Among the schools’ general education students, college is visible at every turn. Teachers display banners and posters from their alma maters on classroom walls. Seniors celebrate signing day, stepping onto a stage to reveal their choice.

If the mantra was “Every student college bound,” Gold reasoned, special education transition students deserved a chance to experience college, albeit not on an actual college campus. She organized Opportunities Academy around college milestones.

“Seniors in [special education] do an application,” says Gold. “When other students are applying to college, those kids are in contact asking if they can come tour: ‘Can I come shadow Doung [Nguyen]?’ And then on senior signing day, they get to say, ‘I’m going to Opportunities Academy.’ ”

Staff don’t take the limiting step of deciding whether a student’s goals are realistic. Instead, they reverse-engineer each student’s pathway in the hope of getting them as far as they can go.

“We have a culture within our whole school where anything is possible,” says Gold. “So if Torion [Grisham] says he wants to be a restaurant manager, cool. That’s going to be the goal, and we go backwards to plan from there.”

Doung Nguyen applied to be Toasty’s cashier. He interviewed for the position and got it. Torian Grisham made even more dramatic progress toward his dream of restaurant management, working part time in a nearby restaurant after school.

Five Toasty’s students are nonverbal and are working on the more basic skills of using technology to communicate. “Class clown” Neptune Nguyen (no relation to Doung), for instance, uses an iPad to interact with the program’s staff.

Because the school is located in an eastern section of the city where restaurants and shops have been slow to return post-Katrina, opening a coffee shop was a no-brainer. Many of the skills involved in running Toasty’s are needed for independent living. There’s money to count, dishes to collect and wash, and relationships to foster and maintain with co-workers and customers.

But it’s also about community. Toasty’s is adjacent to Sci Academy’s front door, and people stop in on their way in and out of the building. Staff can place orders for delivery throughout the day. The sight of the Toasty’s crew out in the halls with the coffee cart is a visual reminder that students with profound disabilities are full participants in the school culture.

“There’s a lot of curriculum out there that role-plays and simulates,” says Gold. “Toasty’s has a real cash register and real products.”

A generation ago, there was virtually no chance that Nguyen and Grisham would have graduated from high school, let alone been encouraged to think about setting career goals and working toward them. In 2001, just 5 percent of students in special education graduated from New Orleans schools. In 2014, 60 percent did.

Louisiana already had begun the takeover of the worst-performing Orleans Parish School Board schools when Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. After the storm, the state Recovery School District seized control of all but the highest-performing schools. Achievement rose as the turnaround district evolved into the nation’s first all-charter system of schools, but concerns about special education persisted.

When their needs became burdensome, students with challenges were often turned away or informally pushed out of schools that were now almost all operating independently. Many cycled from school to school, falling further behind each time.

Schools that did try hard to meet their needs were stretched thin by a lack of basic infrastructure. A decade after the storm, some were still operating in trailers. The number of children in New Orleans who have experienced trauma is mind-boggling.

Money is a perennial issue in special education; its services can be very expensive. State and federal lawmakers have never lived up to their legal obligation to reimburse school districts for the true cost of educating students with disabilities. The shortfall is usually made up by siphoning off funds meant for general education students, creating disincentives to provide children with disabilities all the supports they need.

Without a traditional district structure, New Orleans had to figure out how to minimize the financial risk to schools involved in creating strong special education programs. Some traditional school districts in different parts of the country have revamped their budgeting processes to make sure more state and federal funding meant to help the district’s most challenged students reaches their special education classrooms.

But even in districts moving toward “student-based” funding, money for special education typically is directed to a classroom or a program that supposedly serves students according to their special education classification — such as an autism spectrum disorder or a speech impediment. How well this works for individual students depends on how closely their needs line up with whatever the program offers.

Because most New Orleans schools are public charters, the Recovery School District had to devise a way to give schools the flexibility to provide the right services for their particular student populations. And it needed to create incentives to do that well. In a “choice system,” one where families bid for admission to their preferred program, schools that do a good job with students with disabilities are likely to attract higher special education populations.

New Orleans schools got extra special education dollars based on students’ disability labels, not the level of services needed. If it enrolled lots of high-needs students, a school had to make up the difference from its budget. Surprising no one, the neediest students often couldn’t enroll in their preferred schools or were quickly pushed out.

In 2010, the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a class action over special education conditions in New Orleans schools. In 2014 the district and the civil rights group agreed to a settlement that requires detailed tracking of students served.

By 2013, the percentage of students with disabilities who earned high school diplomas had risen to 48 percent from an appalling 5 percent in 2001. The percentage passing state exams more than doubled, up from 18 percent in 2008 to 44 percent in 2013.

Three years ago the district revamped its rules for reimbursing schools for special education, creating five tiers that provide extra funding according to the intensity of the services students need. A student with a speech or language disability, for instance, receives $1,500 in supplemental aid. A student with autism may receive anywhere from $13,000 to $20,000. Students whose costs exceed $22,000 are funded via a district-wide, high-risk pool.

The Recovery School District also created city-wide systems for student enrollment and discipline, making it much harder to deny admissions to students with disabilities or to push them out by suspending or expelling them. Disabled students are among the most likely to receive harsh discipline.

Collegiate Academies used grant funding from the school innovation incubator New Schools for New Orleans to create several unique special education programs. The schools in the Collegiate network tripled the number of students with autism or intellectual disabilities in its Essential Skills program. And as predicted, the resulting buzz attracted families.

Yet staff knew that for students with moderate to profound needs, there was little opportunity after high school. Enter Gold — and Toasty’s.

The new flexibility allows the program to tailor services to the 11 students enrolled. For the five nonverbal students, for instance, speech therapy happens every day.

“I used to have them one hour a day in skills programs,” says Gold. “Now I have them eight hours a day, which is awesome.”

Education policy advocates are watching the city’s special education overhaul, hoping it yields strategies that can be replicated elsewhere.

“Some New Orleans observers suggest schools under the old funding system have been reluctant to pledge the full array of potential services on a student’s individualized education plan (IEP) because the schools knew they couldn’t pay for it and didn’t want to promise what they couldn’t deliver,” a preliminary analysis from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) said. The report went on to quote Adam Hawf, former assistant superintendent in the Louisiana Department of Education.

“We’d hope to see schools building special expertise and specialization in serving students with really significant disabilities, without fear that they’ll be bankrupted by an influx of those students,” Hawf told the CRPE researchers. “We’d like schools to have the confidence that it’s not just a mandate to serve these students. Now, there are actual positive economies of scale, so there’s an incentive to create great programming that serves these students well.”

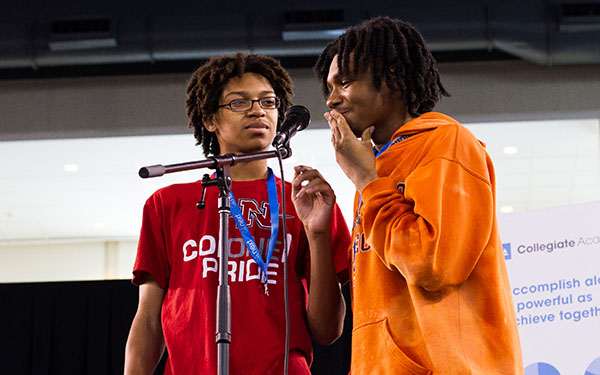

This year, Opportunities Academy expanded to Collegiate’s second high school, Carver Collegiate. The seven students in that program also operate a coffee shop, Java Ram — named after the school’s storied sports teams.

Grisham, now a graduate, was back on a recent day as a volunteer, helping Carver’s transition students with gym activities tailored to their abilities. There’s also yoga and, once a month, a hotly anticipated dance party.

One of the students he gets to mentor is Romallis Ison, now in his first year in the program. He has an internship helping to organize classroom supplies as well as a job in the cafeteria.

“I hope I get a job like Opportunities Academy,” he says. “I’d like to get a job by the time I graduate.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)