Of Houses and Hope: A Promising Fort Worth School Turnaround and the Closely Watched Policy Push Making It Happen

Fort Worth

As kids pass in the halls at Como Elementary, the undercurrent of joy about the school’s Harry Potter-style house system is palpable. Banners and other color-coded emblems on display at the Fort Worth, Texas, school identify the societies into which students and educators alike are organized.

Small faces light up when they see the coaches and administrators who are their adult housemates. Fists are bumped and, after a meeting where especially big accomplishments are celebrated, house logo T-shirts are shown off.

The multi-grade houses — philotimo, tolmao, ignosi and pistos, or honor, courage, knowledge and trust — get together once a week and celebrate wins. At the start of the year, the victories are typically small things that are important to building the school’s culture, like passing quietly from class to class. As the school year goes on, the effort needed to gain recognition rises.

That anything Hogwarts would inspire mirth among Como’s third- through fifth-graders was a given. But the houses have had a profound effect on the school staff, too. “It brings that family feeling to the building,” says Assistant Principal Andrew Farr. “Our staff, they don’t view it as, ‘My class is my class.’ These are all our kids.”

Located 5 miles west of downtown Fort Worth, the newly renamed Leadership Academy at Como Elementary has attracted national attention for a number of closely watched school improvement initiatives that are credited with rapid academic gains. To hear the school’s educators tell it, this esprit de corps is what undergirds the three-year-old turnaround effort.

But, in fact, Como is one of five schools that struggled with years of rock-bottom performance before the Fort Worth Independent School District schools rebooted the school, ultimately asking Texas Wesleyan University to step in. That collaboration is a centerpiece of the Texas Partnership Opportunity, a novel effort being watched closely by education leaders and policy wonks nationwide.

It’s described by some boosters as a third way — a means of taking advantage of the freedoms enjoyed by public charter schools while capitalizing on the greater likelihood of community buy-in when schools remain part of their traditional district. In Fort Worth’s case, the specific school-level interventions are borrowed from neighboring Dallas, while the partnership provides financial sustainability and freedom to refine them on the ground.

In the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act, Congress directed states to set aside at least 7 percent of their main federal funding stream under Title I to pay for evidence-based interventions at struggling, impoverished schools. Texas chose to use a portion of this money to fund competitive grants for districts (including charter schools) that wanted to take advantage of the Partnership Opportunity and related, innovation-focused policies.

The nonprofit Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE), which in November published a first-look report on Texas’s interlocking policies, called the state’s decision to direct financial support toward what it calls the System of Great Schools one of its “highest-leverage actions.” This makes available an average of nearly $3 million per partnership, according to the report.

Districts throughout the state are experimenting with partnerships to create expanded early childhood education programs, to re-create school models that have shown success elsewhere and, in the case of three rural districts, to team up to offer an array of career-readiness opportunities the individual districts could not operate on their own. And policymakers elsewhere are watching.

The early experiences of a number of Texas districts — and a field trip to another of the Fort Worth district’s Leadership Academies — were the subject of a recent convening at Texas Wesleyan. Co-hosted by Fort Worth’s Rainwater Charitable Foundation and the nonprofit Empower Schools, which helps districts nationwide plan partnerships, the conference drew leaders from Texas districts of all sizes.

At the gathering, state Education Commissioner Mike Morath outlined his long-standing frustrations with school improvement efforts. Districts and charter school operators often get promising gains from concerted efforts, only to see performance slide in the following years.

“If we know how to make schools better, how do we keep them that good?” he asked attendees at the October meeting. “Is there something about the system itself that keeps us from sustaining performance over time?”

The initiative has its roots in a series of policies Texas enacted in recent years aimed at propelling school districts, including public charter school operators, to act when a school fails to meet academic standards for several years in a row. The law at the center is known colloquially as 1882, the bill number it was assigned when it first moved through the Texas legislature in 2017.

Under 1882, districts that agree to hand operation of one or more schools, failing or not, over to nonprofit partners receive extra funding. The partners — which can be not-for-profit organizations, colleges, universities or charter school networks — agree to performance targets. Schools slated for possible closure because of years of poor performance get two extra years to climb off the state’s “improvement required” list.

The schools run by the partnerships get the same kind of autonomy as public charter schools, with the freedom to hire staff who best meet their needs, dictate the length of the school day and select a model and curriculum. The schools they operate can be low-performing ones, like Como, expansions of existing, successful programs or new schools opened with an eye toward innovation.

On the one hand, say policy wonks tracking the experiment from outside, the partnerships have the potential to spark progress in schools that have failed generations of kids. On the other, says Mary Wells, co-founder and managing partner at Bellwether Education Partners, which has consulted with several Texas districts on 1882, “the risk is districts could use the policy primarily to access additional resources and not do the hard work of designing a school that’s truly unique.”

To date, Wells says, there haven’t been a lot of highly unusual 1882 proposals. “Things that look really boring, well implemented, can have a big impact on student achievement,” she says. “My personal opinion is that really strong implementation is the innovation.”

Which is exactly what Como Principal Valencia Rhines says when asked what’s going right at her school, now in the third year of an ambitious turnaround. The strategies the school is using — extra time, successful teachers, a relentless focus on data and culture — have proven effective elsewhere but are not particularly new. What is new is her freedom to decide the mix that’s right for her school.

Pictures spanning 65 years line Como’s halls, black-and-white photos of teachers and pupils in starched dress outfits giving way to color renderings of kids in jerseys and jeans. There are standard group portraits of classes and teams and hundreds of individuals, meticulously cut out and arranged in neat rows, sporting the fashions of their eras.

“People stop by all the time and say, ‘Oh, I just want to see the school and look for my picture on the wall,’” says Rhines. “Many of our students’ parents went here, grandparents went here.”

Nine of 10 Como students are impoverished, and 21 percent are learning English. Almost a quarter of the student body transfers in or out in a given school year. The surrounding neighborhood is a mash-up of tiny houses in poor repair, ad hoc livestock pens and new homes going up as part of a wave of gentrification.

Despite its position as the heart of the community, the K-5 school has a long history of being among the lowest academic performers in the state. In 2016, just 12 percent of tested students read or performed math at grade level. Even in the most recent years, when it did well enough to climb off of Texas’s “improvement required” list, only 1 in 5 students passed the required state tests.

In 2015, when lawmakers passed a separate bill requiring the state to close a school or take over the district’s board if the school has failed to meet standards for five consecutive years (three, in the case of a charter school), Como’s fate seemed all but sealed.

But even as the implications of the closure law were becoming clear a few years later, lawmakers passed a bill aimed at seeding district-charter collaborations by enabling outside partnerships. A bonus for schools and districts threatened by the closure law: They could get a two-year reprieve from state sanctions if they allowed a third party to reboot struggling campuses.

Because districts’ partners have full control over hiring, firing and compensation — and, in some cases, directly employ school staff — Texas teachers unions have lobbied against the effort and against the school closure law.

In 2018, the San Antonio Independent School District approved a contract with New York-based charter school network Democracy Prep to run a failing elementary school, triggering a lawsuit filed by the district’s teachers union. The suit was dismissed last spring.

The most visible opposition sprang up in the Houston Independent School District, where continued underperformance at some of the city’s most impoverished schools prompted an area lawmaker to propose limiting the number of consecutive years a school could be labeled “improvement required.”

Two years ago, several Houston schools tripped the threshold for closure. The state gave the district a one-year reprieve because of Hurricane Harvey. This year, Houston School Board members elected not to consider any of several potential nonprofit partners, saying they preferred to pressure lawmakers to overturn the legislation.

Rather than overturn or revise the law, during the 2019 legislative session Texas lawmakers appropriated several pots of money to support teacher pay incentives and other items that complement the partnerships. A suit filed by the Houston board is pending, and the Texas Education Agency recently announced the state will take over the board.

Some reform advocates, too, are skeptical, questioning whether some of the new partnerships, particularly those involving nonprofits established by districts themselves, can truly break from the status quo.

“I imagine there will be a range of these new nonprofits,” says Wells. “I think what it will come down to is, really, what is the district’s intent, and is the district buying into the vision behind 1882?”

Indeed, some of the first 12 schools turned over to outside partners under 1882 in 2018 did not show improvement on state report cards. (None used the model credited with gains in Dallas and Fort Worth.) Without differentiated teacher pay on the table, said district representatives at the October Texas Partnership Opportunity convening, recruiting top teachers to chronically underperforming schools was all but impossible.

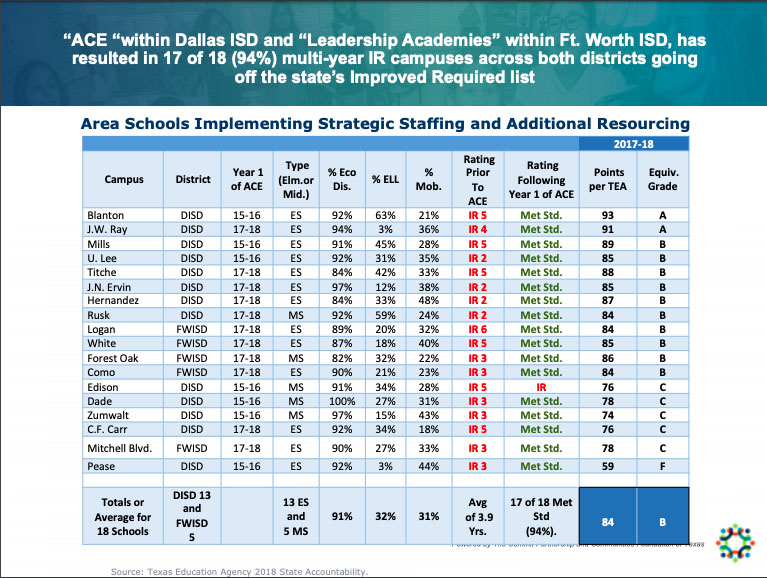

At the time of the law’s passage, Fort Worth, like a number of other districts, had already been planning a turnaround strategy for several low-performing schools, including Como. Next door, Dallas was having initial success with a five-pronged strategy known as Accelerating Campus Excellence, or ACE, which it launched in seven low-performing schools in 2015. Six climbed off the state’s “improvement required” list within the year.

In 2017 — the same year Fort Worth started ACE — Dallas expanded the model to six more campuses, but then a year later it cut funding for a number of the features credited with the schools’ success.

The ACE model is expensive. Administrators with proven track records are paid a premium to take over and reboot a struggling school. As they reconstitute their staffs, ACE principals have stipends — $10,000 in Fort Worth — to lure and keep top-rated teachers, both from the existing employee pool and from other districts. The school day is longer at an ACE school, and students have access to extensive afterschool enrichment programs, three meals a day, uniforms and activities aimed at encouraging family and community engagement and social-emotional learning.

The price tag for implementing the ACE model at Fort Worth’s five Leadership Academies is about $6 million, according to Priscila Dilley, who was executive director of the district’s Office of Innovation and Transformation when it launched the Leadership Academy initiative in 2017. Initially, the local philanthropy Rainwater Charitable Foundation paid for outside planning help and then a number of the program’s features.

At the end of the first year, all five Leadership Academy schools improved enough to get off the “improvement required” list. Four of the schools, Como among them, showed enough growth to earn the equivalent of a B on state report cards.

When the partnership law passed around the same time, Fort Worth saw a path to double down on the model. The increased state funding made ACE sustainable, said Dilley. Texas Wesleyan, the partner the district eventually signed up, allowed its expansion.

In addition to increased teacher and administrator pay, at Como that means five additional staff: two instructional coaches, a counselor, a behavior specialist and a data analyst, who reviews student progress daily. The funds also help underwrite an extra hour of school, enrichment activities from 4 to 6 p.m., three meals a day and uniforms.

None of the Leadership Academies’ new strategies is brand new. Indeed, most have been credited with improving results at schools that outperform their neighbors throughout the country for a decade or more. What’s different about them in this context is that the partner’s performance contract can’t be changed if the political winds shift and bring in a board that, as in Dallas, has a change of heart.

And they are being implemented in concert with, and with the assistance of, outside organizations bringing specialized expertise. The Best in Class Coalition, a group of philanthropies spearheaded by the Communities Foundation of Texas and the nonprofit Commit, has pushed to increase the quality of north Texas’s teacher corps. Without meaningful evaluations, partnership schools would be hard-pressed to identify the right teachers, to help educators polish their skills or to provide the right support so talent doesn’t leave.

Active in five states where officials have created zones of autonomous schools, Empower Schools has helped a number of Texas districts set up their partnerships. The details of the governance structure, including a clear role for the partner’s board, matter, they say.

Last spring, when the district partnership with Texas Wesleyan was announced, the university hired Dilley, allowing her to focus all her attention on improvement efforts at the five schools. Because state funds wouldn’t start until the new academic year, Rainwater provided bridge funding so the summer months would not be lost. Dilley, in turn, was able to hire an academic officer and an operations officer to help oversee progress at the Leadership Academy schools.

So far, adds principal Rhines, the university’s School of Education has been quick to respond to her needs. By way of example, she cites two sets of curricula she wanted to help struggling readers. She needed several of the literacy intervention kits in English and several more for bilingual students, but the $5,000 price tag was prohibitive.

Presented with Rhines’s data, Wesleyan bought a number of the intervention kits, which now perch on tables at the back of Como’s auditorium. Five staff aides pull out kids identified by teachers or the data analyst to work with them. The school also invited in an organization of volunteer literacy coaches.

And then there are the house T-shirts. As the Leadership Academies were getting off the ground, their leaders approached Rainwater about having shirts printed. The foundation’s leaders were poised to make big investments, like the many, many hours a week of enrichment the schools offer.

But after all, recounts Rainwater Program Officer Sarah Geer, the organizations were coming together in an effort built on trust. In the abstract, it was a stretch to understand how T-shirts factored into a vision they were betting on as transformational.

“When you step into these schools, there’s this very felt difference of energy in the school itself,” says Geer. “There’s a feeling of belonging and of pride, of being in this together.

“It’s so much more than putting on a T-shirt. It’s what the T-shirt represents.”

Disclosure: The Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation provides funding for the Best in Class Coalition and The 74. Bellwether Education Partners co-founder Andrew J. Rotherham sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)