‘Nothing Short of Phenomenal’: University Prep Turnaround Sees Colorado’s Highest Test Bump

Updated Sept. 20

Correction: University Prep–Arapahoe Street was one of four Denver schools rated “highly distinguished” by the state at the end of the 2015-16 school year. The number of Denver schools recognized for that achievement was incorrect in an earlier version of the story.

Denver, Colorado

When this year’s state test scores were announced in Colorado in August, families and teachers at University Prep–Steele Street had more than a little celebrating to do. Steele Street’s growth in math was the highest in Colorado in the 2016–17 school year and its growth in reading the highest in Denver.

An astonishing feat for any school, to be sure. But all the more so because last year was the Denver public charter school’s first as a turnaround — a school under new management because its old leaders had failed to serve students adequately.

In 2015–16, just 7 percent of students at what was then called Pioneer Charter School met or exceeded expectations on the state tests in math, and 6.4 percent did in reading. By contrast, last spring 42.5 percent of students were at or above grade level in math and 37 percent in English. That translates to gains of 36 and 31 percentage points, respectively.

“Their growth in the first year was nothing short of phenomenal,” Denver Superintendent Tom Boasberg said. “And it was particularly striking how strong growth was among our highest-needs students.”

His colleague, Jennifer Holladay, executive director of the Denver Public Schools’ Portfolio Management Team, is quick to add that growth was especially strong for University Prep students learning English — a group the district has historically underserved. Critics frequently accuse charter schools of failing to enroll their fair share of the neediest students, but 71 percent of Steele Street students are English language learners, more than twice the overall district rate.

“They’ve flipped the gap,” Holladay says. “The language learners absolutely killed it.”

The scores are proof it was a good decision to turn the fledgling school over to the educators who run its highly successful neighbor, University Prep–Arapahoe Street, Boasberg added. Both University Prep campuses serve a majority of students living in poverty and struggling to keep up academically while learning English.

“It’s an important reminder that when you have a team of teachers and leaders that work very thoughtfully, and with skill and love, of the remarkable things they can accomplish,” said the superintendent, whose district encompasses 199 schools and 92,000 students.

To understand the victory that capped “Year One” of Steele Street’s turnaround, he and the educators in the school say, it’s instructive to look to the 2015–16 school year. District and University Prep leaders dubbed it “Year Zero,” the year they intentionally set aside for the transition from one school model to another.

For fifth-grade teacher Andrew Cahalan, Year Zero was pivotal. He moved to Denver the year before to teach at Pioneer, only to have things fall apart. Students were struggling and leadership was in churn. A few months into his new job, Cahalan learned the school would cede its charter — its permission to operate independently — back to Denver Public Schools.

The school remained Pioneer for the next year, but folks from University Prep–Arapahoe Street started appearing in the building, just getting to know teachers, students, and parents. Faculty would have the following year, Year Zero, to decide whether they wanted to join University Prep’s turnaround team. Needless to say, Pioneer’s teachers were wary, says Cahalan.

University Prep believes in intensive teacher training, and at the end of the 2014–15 school year, the summer before Year Zero began, its leaders invited Pioneer’s faculty to participate in its four-week Summer Institute. Cahalan’s alternative being a possible move back to South Dakota, where he went to graduate school, he signed up.

Among other skills, he picked up a group of classroom strategies called the “Super Six.” Even before returning to the classroom, Cahalan was excited about the tactics, drawn from Teach Like a Champion. A compendium of techniques borrowed from highly successful schools, the book is by Doug Lemov, the former managing director of the Uncommon Schools network.

From day one of Year Zero, the Super Six worked for Cahalan, though he harbored doubts, remaining on the fence about whether to look for a new job. And then late in the fall, Pioneer’s other fifth-grade teacher quit, leaving the school in a lurch.

Because of the impending leadership change, the only option was to hire a rotating cast of substitutes, which would be disastrous for students who were already years behind, Cahalan said.

Cahalan took a deep breath and volunteered to combine both fifth-grade classes. When he left for winter break he had 18 kids; when he came back he had 36. In truth, he thought it might implode. But to his utter amazement, all 36 kids in the merged classroom did just fine. Amazingly well, in fact.

“Anything can work with 15 kids,” Cahalan says. “But to have double or more and still have it work? I’m bought in.”

To be fair, he says, there were Pioneer teachers who did the training and still chose to leave the school. And there were some who were defensive or insulted.

In the end, Cahalan was one of six Pioneer staffers who were offered positions as the school officially was transferred to University Prep. Four teachers were hired along with two operations staffers; two of the teachers have since left because of changes in family status.

Year One blew Year Zero out of the water, he says. His fifth-grade class, again, started in August with students performing at the second-grade level in math and third-grade level in reading. By late October, the entire class was working on fifth-grade material.

“We’re obsessed with supporting and developing our teachers,” says University Prep Executive Director David Singer. “We use very intentional strategies of support to make sure they’re successful.”

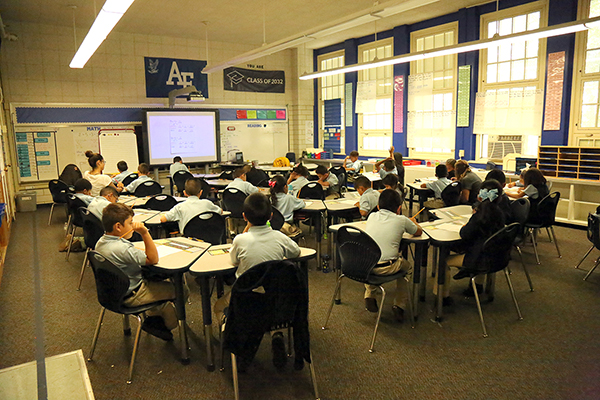

For example, half of the summer institute Cahalan attended is dedicated to practicing — live and in front of others — what Singer calls “explicit skills for delivering instruction.” This includes Super Six techniques such as cold-calling on students so no one can check out, using “wait time” to signal to students that they need to think about their answer to a question and not allowing students who don’t immediately know the answer to opt out.

With school in session, teachers are supported in collecting and analyzing detailed information on each student’s strengths and challenges, which is how Cahalan was able to plug the skills gaps for students last year who were two and three years behind.

Teachers are observed each week and participate in weekly training and data meetings. The idea is not to “catch” underperforming staff but to identify specific skills that would help a teacher reach a particular group of students.

All of which meant even more extra work in Year Zero.

“We overstaffed [Arapahoe] to prep enough leaders, teachers, and operations folks” to spend time at Steele Street, said Singer. “We also wanted to make sure we didn’t take everyone from our first campus and subsequently hurt that campus.”

Although turnarounds are often abrupt and chaotic, experience has taught DPS that lead time — a Year Zero, if you will — is key.

“The work is so complex and requires such thought,” says Boasberg. “One of our key lessons in turnaround work is to have an entire year of planning.”

Until its closure in 2006, Singer taught math at Denver’s Manual High School.

“I got really frustrated telling kids who were 14, 15, 16 years old they could be anything they wanted to be, but we had missed the opportunity to provide them with a crucial foundation,” he says.

Manual relaunched in 2007, but Singer had acquired a new vision: starting a public charter school that would employ tactics working in schools around the country that were getting outsize gains among challenged students. He undertook a two-year fellowship with the school-leadership incubator Building Excellent Schools in Boston and in 2010 applied to Denver Public Schools for permission to launch University Prep.

The Arapahoe campus opened in 2011 with 100 kindergarten and first-grade students, adding 60 students a year until it was fully enrolled as a K-5 school in 2015–16. At the end of that year, it was one of four Denver schools rated “highly distinguished” by the state.

Arapahoe was the only school in that group whose students almost all qualified for free or reduced-price lunch. The other three elementary schools earning the distinction had an average poverty rate of 13 percent.

Year Zero was the first year at Pioneer for Mercy Jaramillo’s two children. New to the area, she chose the school because it was across the street from her mother’s work. Her daughter Trinity started and ended kindergarten at the school a little behind. Her son Eladio, on the other hand, really struggled in second grade.

“He’s very advanced,” Jaramillo says. “At Pioneer, he would do all the work and then just get bored. Then he’d misbehave or cause a ruckus.”

Like Cahalan, her first reaction upon hearing the news that Pioneer would close was fear that she’d have to move again. In the middle of the transition she was diagnosed with cervical cancer, putting extra stress on the family.

And the first conversation of the new year was a tough one. At the start of the first year as Steele Street, the school’s new leaders sat down with every family with students in the building and had candid, sometimes difficult conversations about where each student was performing.

A typical conversation, according to Singer: “Your fourth-grader is phenomenal, we love him, he’s great. And he reads like a first-grader. And here’s what we’re going to do about it.” The plan was to do both catch-up work and grade-level work with almost every student.

“When we got in the door and assessed every kid, it was unbelievable to see how far behind kids really were,” says Singer. “It was hard to see the tears in parents’ eyes. No one had ever been honest with them.”

It helped that the adults contending with both sets of the brutal news had spent the transition year visiting families at home and getting to know them at events. The constant communication about expectations put everyone on the same page, says Jaramillo.

After the school turnaround, Jaramillo says, both her children flourished. Trinity caught up right away and Eladio is challenged by harder work in class.

“His attitude completely changed from one year to the next,” his mother says. “He’s more excited and there’s no having to fight him.”

Holladay, DPS’s portfolio manager, is the person responsible for monitoring University Prep’s performance, which ultimately determines whether its operating charter will be renewed and whether the program can grow. The district occasionally provides the school with technical assistance and is watching the intensive teacher training closely, she said.

In her view, respecting the school’s autonomy has been key: “Part of it was just, honestly, getting out of the way and letting them put their plan into place.”

Last spring, DPS approved University Prep’s request for permission to operate four new charter schools. The fledgling network plans to use them to continue its school turnaround work by taking over struggling schools, whether traditional district or charter. Leaders hope to open a third school a year from now.

“Everyone who goes into turnaround work knows it’s just going to take more,” says Singer. “We don’t think there’s a simple solution.”

But there is a huge payoff, he adds: “There is a definitive proof point that poverty is not destiny.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)