‘Not Acceptable’: Why So Many Hawaii Schools Lack Fire Alarms

A recent report from a House working group highlights the lack of working fire alarm systems and other safety precautions in some public schools.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

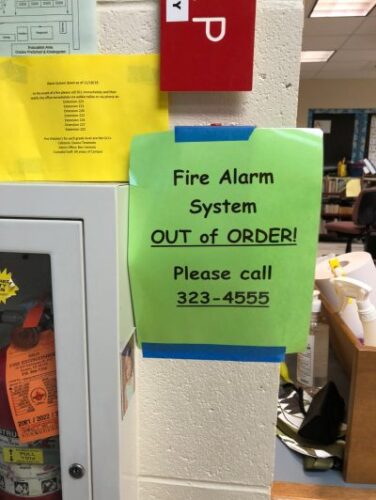

Val Kalahiki isn’t sure her students know what a fire alarm sounds like. In November 2019, Konawaena Elementary’s fire alarm system broke, and it hasn’t been replaced, said Kalahiki, who runs the after-school program at the Hawaii island school.

In the case of a fire, the main office can use the loudspeaker system to inform students and teachers, Kalahiki said. But after the main office closes at 4:30 p.m., Kalahiki said she has to remain extra vigilant as she oversees 130 students who remain on campus for the after-school program.

“Where is the state putting all of our money if they can’t even protect our kids?” Kalahiki said.

Her school is one of over two dozen that lacks a working fire alarm, according to Department of Education estimates.

Concern for school fire safety has gained urgency following the Aug. 8 Maui wildfires that killed 99 people and destroyed more than 2,200 structures, including King Kamehameha III Elementary in Lahaina.

The state House Schools Working Group, formed in the aftermath of the Lahaina fires, released a draft report earlier this month finding some Hawaii schools “vulnerable to fire.” The report offered recommendations for better protecting students, from updating schools’ fire sprinkler systems to making evacuation plans more accessible to the public.

Increased Urgency

But the problems long predated the Maui fires, with some schools waiting years to have broken fire alarm systems repaired. In a House education committee hearing in March, Department of Education deputy superintendent Curt Otaguro estimated that while 80% of Hawaii schools had working fire alarms, 12% had alarm systems in critical condition.

“That’s just not acceptable,” Otaguro said in the hearing.

DOE spokeswoman Nanea Kalani said the department now has 28 fire alarm systems needing repairs. Over 250 public schools fall under the DOE system.

Randall Tanaka, assistant superintendent for the office of facilities and operations, said DOE has made repairs to some systems since the spring, but larger repairs need more time since some require updates to schools’ electrical wiring systems.

“It’s a high priority for us,” Tanaka said.

Many of Hawaii’s public schools are over 100 years old.

“A significant number of school buildings in Hawaii lack modern fire suppression systems, such as automatic fire sprinklers and fire alarms, leaving them vulnerable in the event of a fire,” the House Schools Working Group draft report said.

The House has scheduled a public hearing Thursday to seek feedback on the schools working group’s findings. A final report on that and other Maui-related topics is due Dec. 15. The DOE said it is still looking over the report but will submit testimony by Thursday.

Broken Systems, Delayed Repairs

County fire departments conduct inspections on schools every year. To pass these inspections, schools need to have working fire alarm systems, said Parrish Purdy, captain of the fire prevention bureau for Maui County.

DOE said 90% of its schools passed their fire inspections in the 2022-23 school year.

But for schools with broken alarm systems, it can sometimes take years to receive replacements or repairs.

For example, as of 2017, the Department of Education acknowledged that King Intermediate School on Oahu had lacked a working fire alarm system for seven years.

If campuses have broken fire alarm systems, they must go on fire watch, said Kendall Ching, a captain with the Honolulu Fire Department. That means teachers and staff members are responsible for notifying the school’s administration and the fire department if they see signs of a potential blaze.

There’s no time limit on how long a school can remain on fire watch, but it’s not meant to be a long-term solution, Purdy said.

In January 2021, fire watch protocols helped to keep an electrical fire from spreading on Konawaena Elementary’s campus. Second-grade teacher Anika Agerlie said she’s grateful a custodian was on campus and quickly alerted the school administration, but she worries what would have happened if the fire wasn’t caught early on.

“Four years is way too long to be on fire watch,” Agerlie said. “One year is way too long”

Legislative Action Planned

Rep. Jeanne Kapela represents District 5 on Hawaii island, which previously included Konawaena Elementary before redistricting. In the 2023 legislative session, she introduced and passed House Resolution 55, which requested the DOE to submit a list of schools with broken fire alarms and a timeline for completing these repairs.

The House Education Committee has not yet received the DOE’s list, Kapela said.

Kapela said she plans to introduce a bill next year providing funding to fix schools’ fire alarm systems. DOE said it would need to spend $10 million annually for the next five years to complete its repairs.

“There’s no alternative to having a working fire alarm,” Kapela said.

Tanaka is unsure of the exact timeline for fixing schools’ fire alarm systems but said the DOE is constantly searching for solutions. He added that a shortage of companies who are able to fix schools’ fire alarm systems has contributed to delays.

Structural Changes

Since the August wildfires, DOE has focused on keeping the perimeters of schools safe and has worked with the Department of Transportation to cut down the grass and dry brush surrounding campuses such as Lahainaluna High, Tanaka said. He added that DOE is evaluating available emergency escape routes for schools, pointing to the emergency access route leading out of the Lahaina schools that DOT constructed last month.

He added that DOE continues to assess the fire preparedness of schools, particularly in fire-prone areas.

When it comes to building new schools or renovating old ones, the state is working with the National Council on School Facilities and the Environmental Protection Agency to ensure campuses have fire-safe infrastructures, said Keone Farias, executive director of the School Facilities Authority. For example, he said, the EPA’s guidance on what building materials are most fire-resistant will inform projects moving forward.

Farias said SFA hasn’t yet been involved in conversations around rebuilding King Kamehameha III’s permanent campus. But, he added, the agency will take all the precautions to protect the school when the time comes.

“We’ll build the safest school we possibly can,” Farias said.

Civil Beat’s education reporting is supported by a grant from Chamberlin Family Philanthropy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)