‘No One’s Fighting for Us’: How One Rural School on Nevada’s Walker River Reservation Is Striving to Keep Native Students On Track Through the Pandemic

This piece, originally published by The Nevada Independent, is part of a collaborative pandemic reporting project led by the Institute for Nonprofit News and member newsrooms. (See more rural case studies at The 74)

Before class on a warm and sunny December morning, eight kindergarten students at Schurz Elementary School listened quietly as the Shoshone Indian Flag song played over their computer screens.

The lyrics, translated to English from the Shoshone language, mean, “Across the big water, the red, white and blue is fluttering in the wind. War spear thrown in the ground by a foreign water.”

This is how students begin their virtual school day on the Walker River reservation, which spans 325,000 acres across the Nevada desert, east of Yerington and north of Hawthorne. Surrounded by mountains, the river valley is home to a little more than 1,000 people. And 69 of the 72 students who attend Schurz Elementary School, which sits on the reservation, are American Indian.

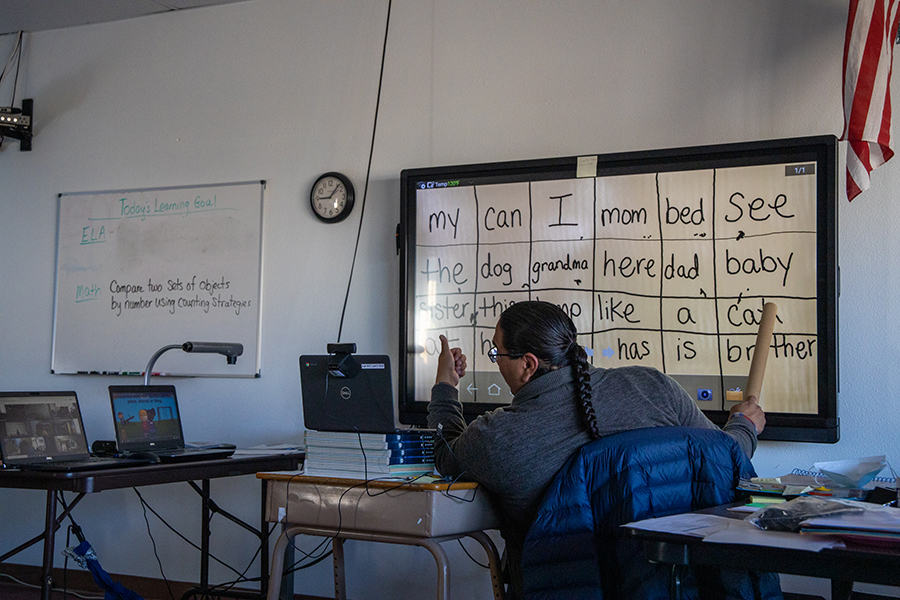

The school’s principal, Lance West, who’s filling in for a teacher on medical leave, waits for the song to finish before diving into traditional academics: studying the alphabet, identifying nouns and reading with partners.

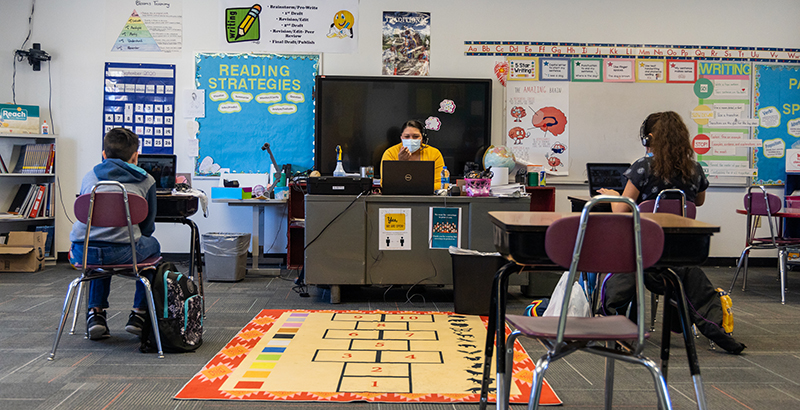

The school operates on a hybrid schedule in response to the pandemic, with some students learning in person at school and others connected virtually from home, split into morning and afternoon sessions. On this morning, West is in the classroom speaking to a computer screen, with the kindergarteners’ faces staring back at him.

The small, empty room looks like most kindergarten classrooms, full of colorful wall art, rugs with numbers and letters, miniature tables and chairs fit for 5-year-olds. But a tribal drum and a poster depicting Native American children, adults and elders distinguish the space as a classroom on a Native reservation.

The public school, which is part of the Mineral County School District, is about two hours southeast of Reno. The remote location jibes with a 2010 Civil Rights Project report, which found that American Indian students are more likely to attend school in rural areas than non-Native students. Additionally, about a third of Native students nationwide attend schools in which at least half the student population is American Indian.

Of the school’s six teachers, four are Native American, five if you count Principal West.

Although he is an enrolled member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, West grew up in this community on the Walker River reservation, his family split between the two tribes and reservations. He once sat in the same miniature seats as the ones in this classroom.

His path to the principal gig on Walker River reservation wasn’t direct. He lived and taught in schools across Northern Nevada — in Reno, Fort McDermitt and Spring Creek — for 17 years before returning to the reservation. He came with a singular goal of improving education for the young Native people in his community, and therefore contributing to the community at large, and for the long run.

“No one’s fighting for us,” West said. “Well, hard enough. So that’s kind of where my push is now, and everywhere I go, I’m always talking about Indian education.”

But improving education for Native students is a daunting task for a single person to tackle, weighed down by historical disparities that cannot be resolved or remedied overnight. Nationally and statewide, American Indian students have low graduation rates, high dropout rates, low math and reading proficiency scores and often don’t see themselves reflected in their teachers, many of whom are white.

It’s a situation, West said, built on years of systemic racism — the same racism behind federal boarding schools, where young Native children were separated from their families and forced to assimilate into American culture and society. Consider what Indian School Secretary John B. Riley said in 1886:

“Education affords the true solution to the Indian problem … only by complete isolation of the Indian child from his savage antecedents can he be satisfactorily educated.”

More than a century later, Native students still find themselves facing prejudice in other forms, West said.

“There’s a good ol’ boy system that exists and the system is not designed, never was designed for minorities or people of color to be fully successful as they should be,” West said. “There is a racist system, if we’re speaking clearly, particularly toward American Indian populations. Our kids, they’re minimized.”

He’s on a mission to change that. His journey just happens to coincide with a tumultuous period in the history of the nation’s K-12 education system, which has been rattled by the pandemic.

In Nevada, there are almost 4,000 American Indian and Alaskan Native students from pre-kindergarten through 12th grade. It’s the smallest ethnic group. By comparison, Nevada’s school systems include more than 7,000 Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander students, 26,000 Asian students, 56,000 Black students, 209,000 Hispanic students and 144,000 white students.

Nationally, American Indian and Alaskan Native students make up a little more than 1 percent of public school students, or approximately 644,000 students in kindergarten through 12th grade. About 90 percent of all Native students attend public schools, and about 8 percent attend schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Education, under the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

There are 183 schools across the country in 23 states funded by the Bureau of Indian Education, including two in Nevada — a junior and senior high school on the Pyramid Lake reservation north of Reno and an elementary school on the Duckwater reservation south of Eureka. Other schools governed by local districts and the Nevada Department of Education — like Schurz Elementary School — educate a large share of Native students.

Improving education for these students is the priority for Nevada Native leaders, such as West, who say they cannot rely on local, state or federal organizations to take the initiative.

“I think that the topic, the issue of education in Indian Country, in Nevada, has always been near the bottom. It’s always been in someone else’s hands, but at the same time those other people’s hands don’t have our best interests in mind, because they have their own,” West said.

Mineral County students trail their peers in other districts when it comes to academic achievement. During the 2018-2019 school year — the most recent year of testing data — only 23 percent of Mineral County students were proficient in math and 39 percent were proficient in English Language Arts. Statewide, 37 percent of students hit proficiency benchmarks for math, while 48 percent did the same for English Language Arts.

At Schurz Elementary School, the achievement gap is even more visible. When 20 students in grades three through sixth took statewide standardized tests in 2019, none of them met proficiency benchmarks for math, and only 10 percent did for English Language Arts.

Of the more than 500 students in the Mineral County School District, 76 are American Indian or Alaskan Native.

Nationally, 19 percent of American Indian and 25 percent of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander students tested at or above proficiency levels in reading compared to 57 percent of Asian students and 45 percent of white students, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

The achievement gap is also reflected in disparities in graduation and dropout rates.

Nevada’s overall graduation rate saw a dip this year, and American Indian students consistently have lower graduation rates than most other racial groups besides Black students. In 2018, nearly 80 percent of American Indian students in Nevada graduated, followed by a drop in 2019 and 2020, when 74 percent of American Indian students graduated both years. That mirrors national graduation rate trends in recent years.

Native students are underrepresented in graduation rates, and overrepresented in dropout rates. In 2018, among students ages 16 to 24, American Indian students had the highest national dropout rate: 10 percent of students, compared to 4.8 percent of white students.

The situation creates a natural ripple effect for post-secondary education. Of the more than 600 people over the age of 25 living on the Walker River reservation, an estimated 86 percent have completed high school, but only 5.7 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

The academic disparities contribute to cycles of poverty on reservations, where unemployment rates are high and rates of home ownership are low.

Prior to the pandemic, the unemployment rate on the Walker River reservation stood at 22 percent, while the statewide unemployment rate was 3.7 percent in December 2019.

Additionally, the median household income for the reservation from 2015 to 2019 was a little more than $30,000, while the median household income in Nevada was double that, at more than $60,000 during the same time period. Of all families living on the reservation, an estimated 39 percent live below the poverty level, including nearly 57 percent of families with school-age children.

Other troubling disparities linked to low graduation and high dropout rates include higher than average incarceration and suicide rates among Native youth.

The academic, economic and mental health disparities among the Native population are historical and decades-long. Native leaders acknowledge the reality of these disparities, but to pave a way forward, they want to shift the focus from the disparities, which some say have created harmful stereotypes, to solutions, visibility and empowerment.

In 2018, principal West created the Indigenous Educators Empowerment group to boost conversations about and support for Native teachers. Since then, West has focused on reaching out to other Native educators across the state to join him and build a strong foundation, which includes compiling the research and data necessary to make progress.

Last year, the group also released a report analyzing factors that contribute to low academic achievement among Native students. Among the challenges: opportunity gaps, systemic racism, low teacher expectations and qualifications, and a lack of culturally relevant curriculum addressing Native history and generational trauma.

“Society’s narrative of us revolves around the Deficit Ideology,” the report states. “… This ideology generalizes disparities such as poverty, alcoholism, at-risk students. We have intentionally left out those reasons for low academic achievement of our students out. They play a role, but to emphasize them would propagate stereotypes and labeling.”

The pandemic, of course, added a new wrinkle in Native leaders’ quest to dramatically improve education. But it wasn’t all bad.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has generally intensified existing disparities, both West and Schurz Elementary School teacher Kellie Harry said the school’s response to the pandemic helped bridge the technology gap, making the learning material more accessible for students and their families.

“Nobody’s missing anything,” said Harry, who teaches fifth- and sixth-graders.

Prior to the pandemic, 80 percent of households on the Walker River reservation had a computer, but only 60 percent had access to broadband internet service. Now, every single family with a student has a computer or a Chromebook and internet access.

The Walker River Paiute Tribe received more than $20 million from the CARES Act and put some of those funds toward ensuring students would have what they needed to distance learn from home. Tribal members can also apply to receive $1,000 monthly stipends to help cushion the economic blow caused by the pandemic and help pay for the internet service.

The fiscal cliff — a Dec. 31 deadline for using CARES Act funding — had worried Amber Torres, chairman of the Walker River Paiute Tribe. If that money suddenly went away, she wondered how families would be able to maintain internet service during distance learning.

“We don’t have that kind of money lying around to continue to pay for these homes,” she said.

But the news that Congress approved a $900 billion relief bill on Dec. 21 brought some welcome mental relief to Torres and other tribal leaders. Torres described the legislation, which was signed by the president and includes money for expanding broadband services, as “an absolute win for not only Nevada but Indian Country as a whole.”

From a day-to-day learning standpoint, though, Harry said the most challenging part of the pandemic was familiarizing the students and parents to the new technology.

“The hardest transition was just getting everybody on board with the online and feeling comfortable. I think there was a lot of hesitancy and a lot of fear on the home front, like, ‘Wait, how do we get on the internet? How do we use the computer or the online platforms? Or what’s the login and what’s this?’ I think that was the most difficult part, and then just streamlining that.”

Several months later, after acclimating to the new learning model, Harry has seen greater academic equity in her classroom.

“Now our students are at an equal playing field. This brought equity to our school, distance learning did — getting everybody on the internet, getting everybody on a Chromebook and having them be required to do the work that other five-star schools or other schools are doing,” she said.

The new technology skills, she said, will pay dividends down the road as students enter junior high and beyond. Harry added that she’s not worried about a lag in academic performance among her distance-learning students.

“The performance is the same. I have a lot of distance learners who are outpacing and keeping up and have made a lot of growth on their math scores and keeping up with all the coursework just as easily as if they were right here,” she said.

Older students appear to have struggled more with online learning. When students graduate from Schurz Elementary School, which goes through sixth grade, they can choose what neighboring school district to attend for upper grades. For students on the Walker River reservation, that’s typically schools in Hawthorne or Yerington, although some go farther north to Pyramid Lake.

Yerington High School, which is in the Lyon County School District, employs a college career coach — with the help of a federal grant — who works exclusively with Native students, said Wayne Workman, the district’s superintendent. When the Lyon County School District began the 2020-2021 academic year, only select student groups received in-person instruction five days a week. Those groups included children in kindergarten through second grade as well as students in special-education programs, learning English as a second language or experiencing homelessness.

The decision boiled down to space constraints while operating under COVID-19 safety guidelines, Workman said. All other students were split into cohorts that rotate between a week of in-person learning followed by a week of online learning.

But more than a quarter of Lyon County students opted to remain in distance-education mode, giving schools more flexibility to expand in-person instruction, Workman said. So by early October, Yerington High School started welcoming back Native students full time after noticing the hybrid model wasn’t working well for them.

“If they’re here, I can motivate them to continue on a successful path,” said Gerald Hunter, college and career coach at Yerington High School. “If they’re home, I’m competing with TV, food, babysitting duties, other things.”

Yerington High School has 398 students, including 74 who are Native American, in ninth- through 12th-grade. Hunter, who’s in his fourth year serving as the college and career coach, has watched discipline and truancy problems fall among Native students, while seeing their academic achievement improve. Last year, 70 percent of the school’s Native students maintained at least a 3.0 grade-point average.

The majority of Native students chose to return to in-person instruction five days a week, Hunter said, and their grades have improved as a result. Some Native students remain in distance education, though, because of health concerns amid the pandemic.

While Hunter’s presence has helped boost academic achievement levels among Native students, Workman said, it hasn’t been a cure-all. Providing extra supports simply doesn’t reverse history and longstanding inequities that have led to Native students trailing their peers academically.

“We could talk for hours as to reasons why that might be the case,” he said. “For goodness sakes — how we treated our Native populations forever in our history has led to a lot of distrust.”

Back on the reservation, Harry is hoping Schurz Elementary School can preserve its pandemic-triggered 1-to-1 technology ratio for students that’s proven to help ensure the quality of education for her students. The great unknown, though, is how the school, like others across the state, will fare during the upcoming 2021 legislative session.

“It’s just keeping what we have,” Principal West said, “especially with the budget cuts coming.”

Despite the grim circumstances caused by the pandemic and an already slashed state education budget, West isn’t limiting his goals and vision for the future of Native education.

When he created the Indigenous Educators Empowerment group, West had four goals — to boost education awareness among the community, advocate for Indigenous education professionals, enhance recruitment and mentorship for Indigenous educators and revitalize and preserve Native language.

The 2020 Indigenous Educators Empowerment report offers recommendations for how to get there, such as advocating for more funding, bolster tribal and state leader involvement in efforts to improve education and establish scholarships for tribal members interested in becoming teachers.

But West said everything hinges on more data and recordkeeping.

Native students belong to what Native leaders call the “Asterisk Nation,” because of the population’s small sample size, American Indians are commonly left out of research and data collection.

“The data is lacking,” said West. “How do you expect us to address education and seek that improvement that has never ever really been a focus if we don’t have accurate information?”

Armed with more reliable data, Native leaders such as West can provide benchmarks and guidance for state and federal agencies in regards to allocating funding and other resources for Native students. Increased data will also make Native students, their communities and the issues they face more visible.

Long-term goals also include efforts to exercise educational sovereignty, specifically, by establishing a tribal charter school on the reservation, beginning with younger children and eventually expanding to serve students through high school. With a charter school, the tribe and educational leaders could take full ownership and control of what their students learn and how they learn it — sovereignty.

The other goal is to establish “Indian Education for All” as state law, meaning the state would require Native history and culture to be included in the curriculum for all grades in public schools.

West has already started down that path at Schurz Elementary School, where the curriculum includes more Nevada Native history, to ensure the students learn about their identity in a positive and empowering way. He’s also made it a point to recruit more Native educators to build the representation for the Native students.

“Our Indian kids here need to see more of themselves reflected in the classroom and they need to see Native teachers,” West said.

West recruited Harry, who was previously teaching in the Washoe County School District at Depoali Middle School in South Reno, two years ago. Harry is an enrolled member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe as well, but half of her family grew up on the Walker River reservation. Now, a majority of the school’s teachers are Native.

“If there’s a chance to get back and contribute, that’s what I think our life’s journey is about,” Harry said. “Our purpose, mine anyways, as teachers, we want to give back and contribute. So that’s what brought me here to Schurz.”

Less than 1 percent of educators nationwide and in Nevada are American Indian or Alaskan Native. Harry said the representation she provides for her students helps create a sense of safety in the classroom.

“I think that it’s beyond words and beyond impactful for the students to have a Native teacher. And that’s why I did not hesitate to come out here. It was really hard to leave where I was, I had to move my family and my kids, but I would not have ever second-guessed coming here because of the unique situation and what I’m able to provide and contribute.”

In the last two quarters, Harry has incorporated lessons about the history of voting rights for Native people, Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples Day and what it means to her students to be Native American. Her curriculum is more timely and relevant than the Native American history and imagery in textbooks, which usually focus on events prior to 1900, according to a 2015 study, thus contributing to the erasure of the modern presence of Native communities.

Harry recently asked her students to complete a written exercise exploring their Native identity. Their responses, submitted in late November, highlighted Native language, traditional dress, ceremonial events, such as pine-nut gathering, hunting and basket-weaving.

But the students didn’t just write about these things in the past tense — and, as far as tribal leaders are concerned, that’s evidence of educational progress.

“We are proud people by showing respect to family and friends,” wrote one student, Suiti Sanchez, 10. “We honor our ancestors by keeping our traditions alive. We respect elders by learning our language and by passing our traditions to others.”

This piece, originally published by The Nevada Independent, is part of a collaborative reporting project called “Lesson Plans: Rural schools grapple with COVID-19”. It includes the Institute for Nonprofit News, Charlottesville Tomorrow, El Paso Matters, Iowa Watch, The Nevada Independent, New Mexico in Depth, Underscore News/Pamplin Media Group and Wisconsin Watch/The Badger Project. The collaboration was made possible by a grant from the Walton Family Foundation, which also funds The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)