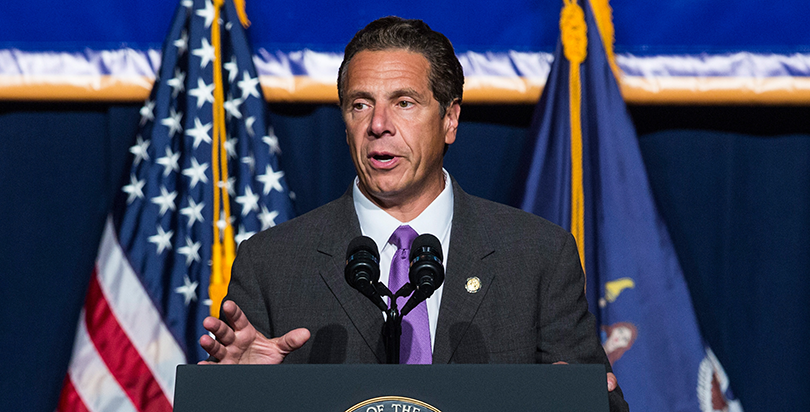

The New York education world has been buzzing since Gov. Andrew Cuomo purportedly backed off his once-staunch push to strengthen the link between test scores and teacher evaluations — a move that was widely reported as a huge concession to the state’s successful parent- and union-driven opt-out movement.

In the weeks leading up to the New Year, Chalkbeat reported that Cuomo’s Common Core commission had

proposed “pausing test-based teacher evaluations” through the 2018-19 school year; The New York Times

called the move a sharp reversal of the state’s policy from earlier this year when the legislature increased the weight of test scores in evaluations.

Negative editorials began rolling in: The Wall Street Journal

bashed Cuomo for adopting “a moratorium on test-based teacher evaluations.” The New York Post editorial board

claimed “any serious consequences for rotten teachers” are now “banned.”

The roughly 600,000-member New York State United Teachers union in its statement termed the moratorium the beginning of the end of a “test-and-punish” era, one in a series of commission recommendations that could “restore the joy of teaching and learning to our classrooms.”

A few outlets got it right —

this piece in Politico New York provides a particularly clear explanation — but most media coverage was confusing, even downright wrong.

New York teachers will indeed continue to be rated significantly by some form of student assessment — just not state standardized tests.

Dani Lever, a spokesperson for the governor’s office, confirmed in an email that test-based evaluation is alive and well: “The Common Core Task Force recommended, and the Board of Regents adopted, a moratorium on using the results of Common Core 3-8 ELA and math tests in New York’s teacher evaluation system. However, there is no moratorium on the use of other test scores, and other measures of student learning will continue to be a critical component of a teacher’s evaluation.”

In the absence of state assessments then what will fill the teacher evaluation vacuum? More local tests, which historically in New York have led to higher ratings for teachers than state tests.

Cuomo’s task force tries to douse anti-testing firestorm

In 2010, with the assent of teachers unions, New York

passed a statewide teacher evaluation system that would base 40 percent of the evaluation on test scores, often a combination of state and local assessments.

Last year, Cuomo said that too few teachers received low ratings, and

successfully spearheaded a change to the system that bumped “student learning” to 50 percent of teachers’ ratings. This enraged unions, and helped galvanize an already growing opt-out movement.

Cuomo later appeared to signal retreat by

convening a Common Core Task Force, which made a series of

recommendations in December including the pause in using Common Core-aligned tests in evaluations. The New York Times had earlier

reported that Cuomo planned to institute a moratorium on all test-based evaluations, and most

media outlets suggested that the

regulations adopted in late December by the Board of Regents did just that. The widely repeated storyline became: New York is hitting pause on test-based evaluations.

But state law defies that narrative, and clearly lays out that half of every teacher’s evaluation must be based on some form of student performance

1. The new regulations do nothing to change this and explicitly say that teachers who had been evaluated by state tests — grades 3–8 math and English tests, as well as high school Regents exams — will now be judged using a local assessment

2. These local tests will likely still be aligned to the Common Core because the standards remain in effect.

As Richard Parsons, chair of Cuomo’s task force put it, “The Common Core Task Force did not opine on the state’s teacher evaluation law, and we did not recommend any legislative changes to the law.”

The state Education Department has not issued full guidance to districts yet, so many specifics about the new rules remain unclear. But it appears that the only way to eliminate or postpone the use of test scores altogether in teacher evaluation is for the legislature to amend the law.

Confused message might not appease testing critics

The governor’s task force and the teacher evaluation changes came in response to sharp criticism of testing and the Common Core.

Perhaps that’s why some officials have been inconsistent in describing the impacts of the new regulations. For instance, in a

letter to New York state teachers, education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia claimed that the state had “put the use of assessments for evaluations on hold” and “put a hold on any consequences from the evaluation system until we're sure we've got it right.”

Neither of these statements is accurate, though, as Elia herself makes clear in other parts of her letter. Potential consequences from test-based evaluation — such as tenure denial and dismissal — still exist, just not based on state tests.

It’s not surprising then that the state’s tweaks have failed to appease the harshest critics of testing. The New York State Allies for Public Education, a pro opt-out group,

said it will continue to encourage families to boycott state assessments.

The group also claims, “This moratorium does not reduce testing it actually does the opposite, increases testing and further puts a strain on school districts’ budgets to comply.”

This may very well be true, since a new exam might be needed to judge teachers who used to be evaluated by state tests (which will still be given). Though it’s difficult to know how the hundreds of different districts across the state will address this issue, generally speaking evaluation systems have

led to a proliferation of local tests.

Local tests probably mean higher ratings

While these changes may have been politically driven, whether they are good policy is an open question. Columbia professor Jonah Rockoff said in an interview that he has concerns about emphasizing local tests over state ones.

The state exams use a statistical growth model, often referred to as

value-added3, which attempts to isolate teachers’ impact on student achievement. Rockoff has researched this issue extensively, including co-authoring one the most well-known

studies on the topic, and says, “Value-added methods are the most valid and reliable ways that researchers have come up with to use tests across a large population to assess teacher or school effectiveness.”

On the other hand, Rockoff said that locally developed assessments can be useful and suggested that basing half of a teacher’s rating on value-added is probably too high. But if the goal is improving the quality of the tests, increasing weight on local ones might have the opposite effect.

“We know very little about a lot of these local assessments … In terms of the statistical properties, it’s hard to imagine these assessments are as good as the statewide tests,” Rockoff said.

The elimination of state tests may also lead more teachers to be rated by assessments in subjects they don’t even teach, a practice that exists in New York and several other states.

Research has found that group-based performance measures tend to raise the score of low-performing teachers and lower the score of high performers.

Given all this, why the push to pause just the state assessment?

One answer is that in New York these tests — unlike local measures of student learning — have labeled a meaningful number of teachers ineffective. In the 2013–14 school year, 6 percent of teachers who received a state growth score were

deemed ineffective and 10 percent developing. (Scores are grouped into four areas: highly effective, effective, developing, or ineffective.)

But on the local

assessment, 2 percent were ineffective and 5 percent developing. Overall, just 1 percent of teachers were judged ineffective. And, as The Seventy Four recently

reported, only one tenured teacher has been formally dismissed since New York passed its purportedly tougher evaluation law in 2010, according to the state Education Department.

The exclusion of state test scores will likely push the distribution of scores even higher than it already is. And in that sense the prevailing media narrative has an important grain of truth after all: although legally there is no moratorium on negative consequences based on teacher evaluation, practically there very well may be.

Disclosure: In my previous job at Educators for Excellence – New York, I worked with public school teachers to advocate for certain changes to New York’s teacher evaluation system including a lower weighting of test scores in evaluation, an inclusion of student surveys, and an alternative system for teachers without subject-specific test.

Footnotes:

1. Many New York districts have received a waiver from fully implementing the new evaluation system this year, and thus will rely on the old evaluation protocol, which bases 40 percent of a teacher’s score on student achievement. A New York state Education Department spokesman confirmed that this percent might be lower this year for teachers who are in districts that are using the previous evaluation system and who would have been evaluated partially on a state assessment. (return to story)

2. In law this is known as a ‘student learning objective’ or SLO, the details of which likely vary significantly from district to district. (return to story)

3. Technically the state of New York does not use a value-added model, but a statistically distinct model known as student growth percentiles. (return to story)

;)