‘No Easy Answers’ For Keeping Hawaii’s Smallest Public Schools Open And Thriving

Principals at small schools say they need more money, but some state leaders say school consolidation and closures could be the answer.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

During a rainy recess at Kaaawa Elementary, students in grades kindergarten to six swarmed the school playground, splashing through puddles and racing each other on the field.

Principal Jennifer Luke-Payne greeted children by name, kicking a soccer ball to some students and allowing others to retrieve play equipment from her office. As a teary-eyed kindergartener passed by, Luke-Payne offered him a hug.

“They’re all my babies,” Luke-Payne said.

Just over 120 students attend Kaaawa Elementary. On average, Hawaii’s elementary schools enroll roughly 450 students.

It’s financially difficult to run a school with fewer than 250 students, Luke-Payne said, because enrollment plays a large role in determining how much money schools receive each year. Small schools like Kaaawa Elementary struggle to fund key teaching positions when they’re working with annual budgets of roughly $1 million or less, she added.

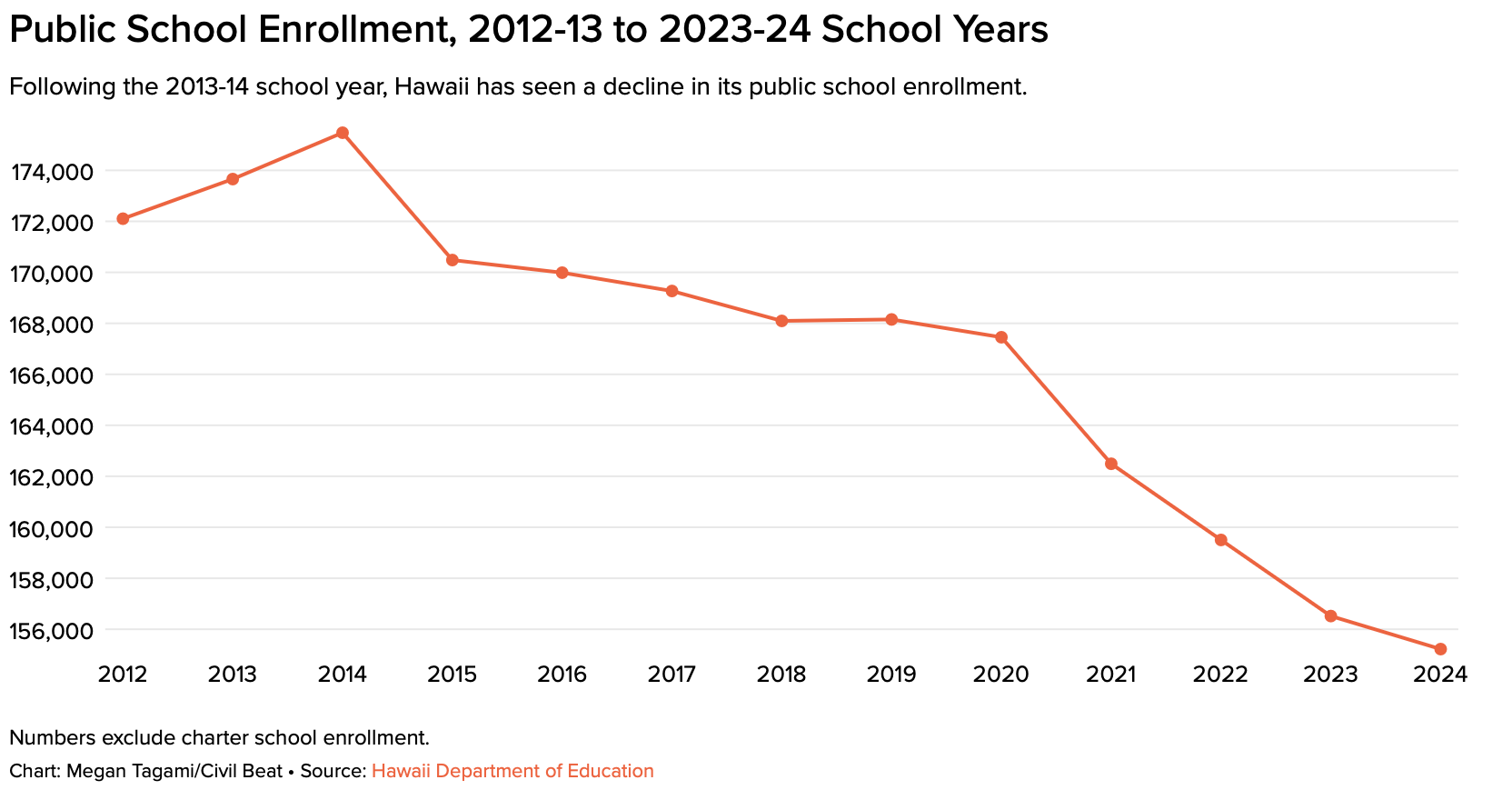

Since 2013, student enrollment in Hawaii’s state-run public schools has steadily declined. Some neighborhoods have aging populations with fewer young children, while other families have enrolled in charter or private schools.

The number of small schools enrolling 250 students or less has grown from 19 to 35 over the past decade. At these schools, annual budgets have come under greater strain, requiring principals to cut teaching positions or eliminate classes like music or physical education.

Legislators recently approved $6 million to supplement the budgets of small and geographically remote schools next academic year. But the additional money is only good for a year, and principals say small schools need more permanent funding sources to stay afloat.

Alternatively, DOE has moved to consolidate or close small schools in the past. These closures have drawn strong opposition from the community, but it’s sometimes necessary when schools are so small they can’t provide a full range of academic and extracurricular opportunities, said Board of Education Chair Roy Takumi.

Takumi anticipates the issue of school closures coming to the board during his tenure, but it’s up to the department to initiate the discussion, he added.

“By design, schools should have a useful shelf life,” Takumi said.

Funding Shortfalls

Kimberly Kaai runs Maunaloa Elementary on Molokai with a budget of roughly $890,000 a year.

The school doesn’t have enough money to pay for a teacher for each grade, so the school combines its kindergarten and first grade class, as well as its fifth and sixth grade classes, Kaai said. As of September, Maunaloa Elementary was the second-smallest school in Hawaii and enrolled 43 students.

The DOE allocates school funding using what’s known as the weighted student formula, a calculation based primarily on the number of students enrolled at each campus. Schools also receive additional money for students with certain characteristics, such as low-income or gifted and talented students.

“That amount from the weighted student formula is definitely not enough to adequately staff our schools,” Kaai said.

Luke-Payne and Waiahole Elementary Principal Alexandra Obra estimate that small elementary schools need annual budgets of at least $1.38 million.

Last summer, a DOE committee studying the weighted student formula identified eight small schools, including Waiahole, Kaaawa and Maunaloa Elementary. All eight schools enroll fewer than 150 students and, as of June, had projected budgets of $1.3 million or less.

Under the new state budget, the eight schools will receive an additional $250,000 for the 2024-25 academic year. Six geographically remote schools on Big Island, Maui, Lanai and Molokai will also receive additional funding.

At Waiahole Elementary, Obra said she’s planning to use the extra money to hire a librarian for the first time. Currently, Obra added, she’s responsible for checking books in and out and cleans the library on the weekends.

But small schools aren’t guaranteed the additional money next year, which can make it challenging for principals to attract and hire teachers, said Marlene Zeug, a consultant who studied small schools and published a report on Kaaawa and Waiahole Elementary in 2022. Principals do their best to fundraise and partner with local organizations to provide more opportunities for their students, she added, but they need a more consistent source of money.

“There’s no easy answers,” Zeug said.

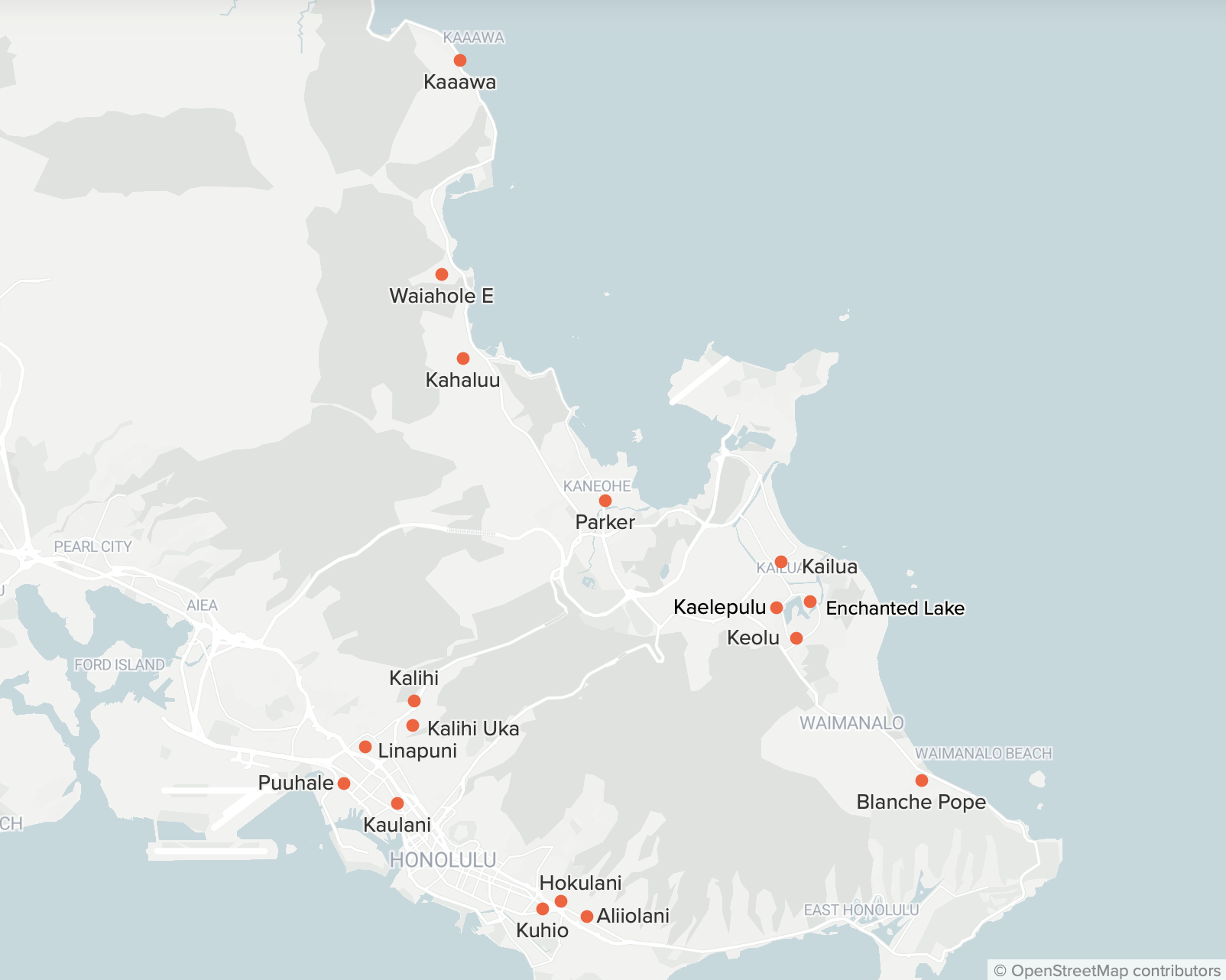

Small Elementary Schools, Honolulu and Windward Districts

Small schools enroll 250 students or less.

Kate Stanley, who served on DOE’s 2023 committee evaluating the weighted student formula, said middle and high schools typically don’t face the same funding challenges as elementary schools because they have larger student populations. But some secondary schools still face tight budgets amid low enrollment numbers.

At Jarrett Middle School, Principal Reid Kuba said he needed to cut a teaching position when enrollment was especially low around 2013. But since then, he added, Jarrett Middle has used its low enrollment to its advantage, encouraging more families to send their kids to the school because of its small class sizes and close-knit community.

Jarrett Middle is still the smallest middle school on Oahu, enrolling 287 students, but Kuba said he hasn’t needed to reduce staffing in recent years.

“We embraced our small school status,” he said.

The Debate Over Closures

Frederick Reppun remembers hearing discussions about closing Waiahole Elementary when he was a third grader in the 1990s. The school remained open, celebrating its 140th anniversary this year, but conversations around consolidation and closure have persisted.

Amid budget cuts in 2008, DOE produced nearly a dozen reports looking into the effects of closing and consolidating elementary and middle schools across the state, including Waiahole’s partner school, Kaaawa Elementary.

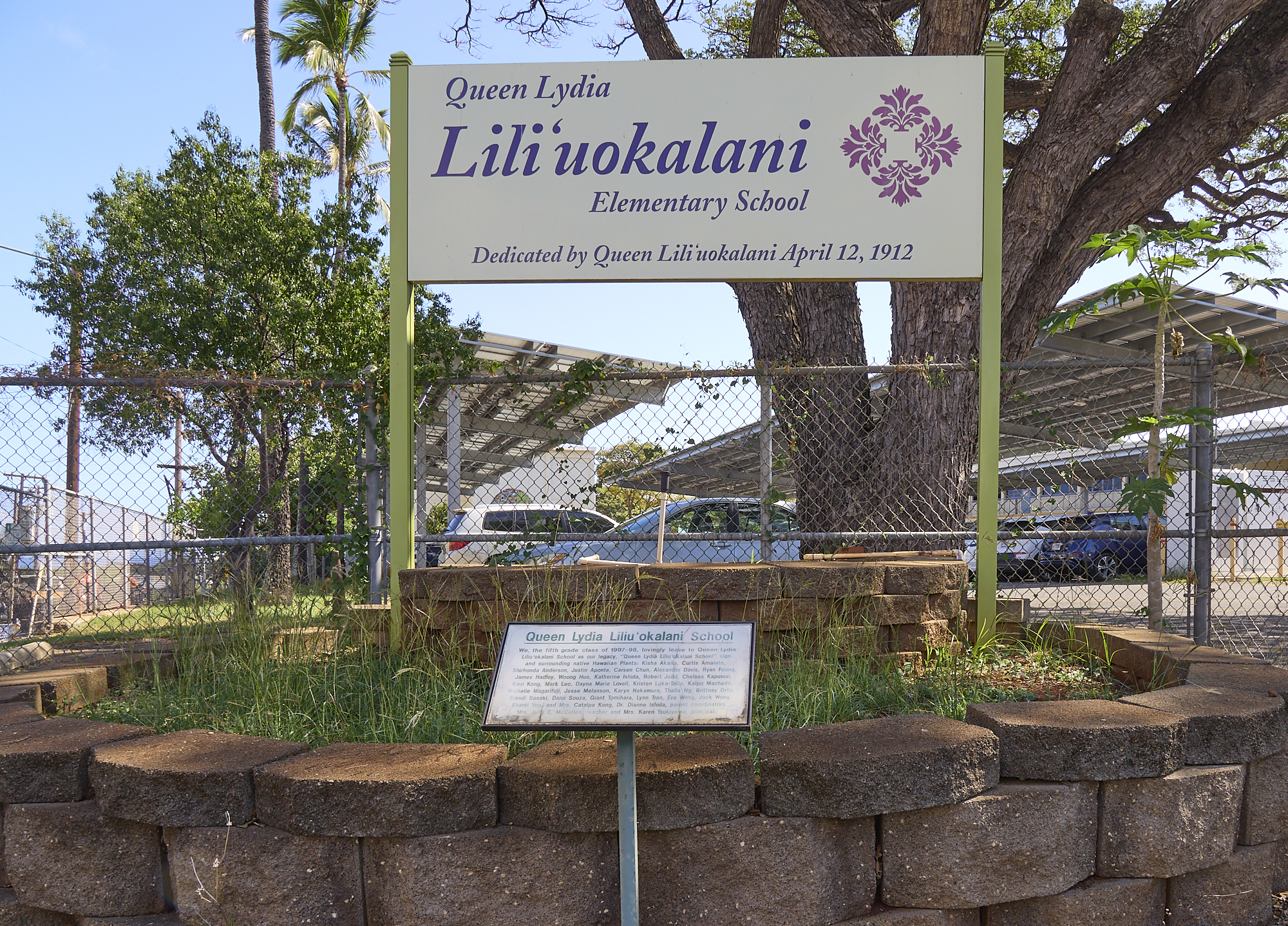

Kaaawa Elementary was spared, but the department closed three elementary schools by 2011 — Wailupe Valley in East Honolulu, Keanae Elementary on Maui and Queen Lydia Liliuokalani Elementary in Kaimuki. Keanae hadn’t enrolled any students since 2003, but community members came out in full force to oppose the closures of Wailupe and Queen Liliuokalani Elementary.

Randy Moore, who was serving as an assistant superintendent in DOE at the time, said closing the schools wasn’t an easy decision. The department needed to assess the quality of small schools’ facilities, the academic opportunities available to students and what campuses families would attend if their current school closed.

Moore, who rejoined DOE as an interim deputy superintendent last week, said he would be surprised if the department didn’t resume its assessment of small schools and the value of keeping them open.

In Kailua, Rep. Lisa Marten said her district could potentially benefit from consolidating schools.

Kaelepulu, Enchanted Lake and Keolu Elementary Schools fall within a 10-minute drive from one another. All three are small schools, enrolling between 91 and 250 students.

Because more families are growing older or sending their children to private schools, Marten said, it makes sense to close the smallest school, Keolu Elementary, and send its students to Enchanted Lake, where enrollment had dropped by half in the past decade. Marten said she worries the two schools are struggling to offer important classes like music, art and physical education.

“When the population goes down, you have to adjust,” Marten said. She added that school closures may not work in rural areas where families have fewer educational options.

But Noel Richardson, principal of Enchanted Lake, said consolidating with Keolu Elementary would be difficult. Keolu Elementary currently provides breakfast and lunch to nearby schools, Richardson said, and it could be challenging to find another campus with the kitchen capacity to produce more daily meals.

“In an effort to save some money, you’ve created a bigger problem,” Richardson said.

At Kaaawa Elementary, Luke-Payne said there’s no shortage of learning opportunities, despite the school’s small size. Behind the school, Kualoa Ranch has donated a small patch of land where students grow kalo and pound poi at the end of the year. Across the street at Kaaawa Beach, students have grown native plants that help to combat beach erosion.

The community rallies to support the school, and every child feels valued on campus, Luke-Payne added.

“I ask them, ‘Who loves you?’, and they point at me,” she said. “They know it.”

Civil Beat’s education reporting is supported by a grant from Chamberlin Family Philanthropy.

This story was originally published in Civil Beat.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)