Exclusive: New York’s Top Ed Policymakers Rush to Save Broken School District After Albany Falters

Albany, NY

Top state education officials say they’re prepared to take real action this summer to stem the crisis in East Ramapo, the New York City suburban school district where powerful private interests have steered the public system on a relentless course toward academic and financial disaster.

“If we go into the school year in September with things as they are now, it is not acceptable,” New York State Board of Regents Chancellor Merryl Tisch told The Seventy Four on Thursday.

Tisch, who chairs the state’s top education policy-making panel, said officials there are “looking at everything” and expect to have a proposal in place to address financial and educational deficiencies cited for at least five years. The board meets Monday.

New York’s new state Education Commissioner MaryEllen Elia, just barely two weeks into the job, also pledged intervention in the East Ramapo crisis. Elia told The Seventy Four on Tuesday that the district’s fate was “one of the big issues” on her agenda. She intends to visit the district and meet with the school board “in a timely way (and it will be) connected to actions that the state Education Department moves forward on.”

East Ramapo, located in Rockland County about 35 miles north of New York City, is unlike any other district under Elia’s watch. More than 8,000 mostly poor and immigrant students attend 14 public schools that are run by a Board of Education controlled by members of the insular Ultra-Orthodox community who send their children to private, religious schools. About 24,000 children in East Ramapo attend more than 100 private schools, mostly yeshivas.

The district’s odd and conflict-laden dynamics have drawn national attention and late last month Tisch took the unusual step of calling publicly for Schools Superintendent Joel Klein’s (no relation to the former New York City schools chancellor) resignation. In a scathing June 3 op-ed in the New York Times entitled “When A School Board Victimizes Kids” she pressed the Albany Legislature to act on an oversight bill and reject the “false attacks” from school board advocates and some in the Orthodox community that the move was driven by anti-Semitism.

“The legislation is not about punishing one group because of its religious beliefs; it is about acting to make sure that the civil rights of a community of overwhelmingly low-income minority children are not denied and that their constitutional right to a sound basic education is enforced,” she wrote.

The full weight of the chancellor — and the hundreds of parents and community members who rallied in Albany — was not enough to secure approval of the oversight bill last month. The Orthodox community, which carries significant sway at the polls, came out in force against it. Foes said a state-appointed monitor’s veto power over school board members’ decisions would effectively disenfranchise the Orthodox voters who elected them.

The oversight bill narrowly passed the Assembly after an emotional, three-hour floor debate but died in the Senate, where lawmakers argued that it would set a dangerous precedent for limiting local school board control.

Meanwhile, East Ramapo’s struggling Haitian, Hispanic and African-American public school families had come closer than they ever had to winning strong oversight of their troubled district — only to be denied.

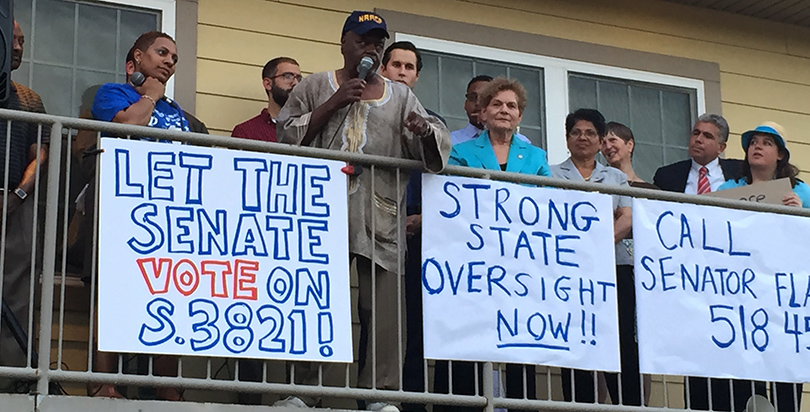

Elected officials and supporters of state oversight for East Ramapo schools rallied in Spring Valley, N.Y. on June 22. On the microphone is Willie Trotman, president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (Photo: Mareesa Nicosia)

Cesia Roman, 15, a student organizer of Strong East Ramapo, plans to step up advocacy efforts in the fall when she returns for her junior year at Spring Valley High School. Roman is nagged by the fear that her classmates – many of whom are recent immigrants – won’t make it to graduation day because there are few, if any, supports in place to meet their needs.

Roman’s parents emigrated from Guatemala; her father works as a gravedigger and landscaper at a local cemetery and her mother runs a daycare out of their home. Unlike some of her classmates, she grew up speaking English and has parents who hold her accountable for getting good grades and staying involved with school activities. Roman plans on being the second in her family, after her older brother, to go to college.

“I take it personal when people don’t have the opportunities that I do,” said Roman, who attended full-day kindergarten (since scaled back to half-day) and plays the trumpet, which she started in fifth grade (before East Ramapo cut its elementary music and art program). “I take it personal when people aren’t able to graduate because they don’t have the required classes. I take it personal when people can’t learn to play an instrument.

“It’s an injustice to have holes in the system and for them (not) to be acknowledged. And for us as a community, we need to show that we’re not done yet. And to show that there’s still hope.”

Over the years, the board has slashed spending on public schools while increasing public spending on private schools, drawing fierce and sometimes ugly confrontations between the board and parents, students and community members. In response to the mounting pressure, Gov. Andrew Cuomo and education officials last year appointed attorney Hank Greenberg to review the district.

What Greenberg found validated critics who’ve long complained that the board operates in secret, is dismissive of parents’ concerns and favors the interests of the private schools when managing East Ramapo’s $200 million-plus budget. Private school students are legally entitled to some financial support from the public schools for items like special education, transportation and textbooks.

Greenberg said the district “teeters on the precipice of fiscal disaster” and recommended a mechanism, such as legislation, that could check school board decisions in real time if they were determined to be detrimental to students or the district’s financial health.

Greenberg’s recommendation became the failed oversight bill. Just prior to the vote, the state Education Department released three damning reports that found “significant failures of leadership” in East Ramapo, especially related to inadequate instruction offered to English Language Learners, who make up one-third of the student population. Read the full report on the bilingual program here.

State officials expressed grave concern about the district’s “proposed segregation” of new immigrant students ages 17-21 who had little previous education into a non-diploma program. The reports also cited the superintendent’s “lack of cultural competency.”

Tisch called the oversight bill’s defeat “reprehensible” and said that legislators had left East Ramapo students “twisting in the wind for another year.” The Senate bill was co-sponsored by state Sen. David Carlucci, who failed to secure support from the leadership.

“Everyone is taking this situation very seriously. And in my opinion, (the school board is) past the point where they are denying everything,” Tisch said in an interview with The Seventy Four. “I think that we are looking towards having a few things in place in the beginning of this school year that will start to say to the community that elected officials (school board members) are taking this very seriously.”

Tisch declined to provide specifics about what steps officials might take and how the corrective actions outlined in the June reports will be enforced. Though it’s a rare step, the education commissioner can, by law, remove school officials for “willful misconduct or neglect of duty.”

More likely, state officials will start by negotiating with the school board to replace Klein, the superintendent.

In a sign that the school board may cooperate more openly with the state, school board President Yehuda Weissmandl recently met in person with Tisch and Judith Johnson, the Regents trustee who represents the district, for the first time, a district spokesman said.

Weissmandl declined to be interviewed. His attitude has seemingly evolved in the last year: In June 2014, he accused Cuomo and former education Commissioner John King of “acceding to the demands of bigots” by appointing Greenberg.

In recent press interviews, though, Weissmandl has moved closer than ever before to acknowledging the board’s part in East Ramapo’s problems.

“We have to work harder,” he said Thursday in an interview with Susan Arbetter on “The Capitol Pressroom” radio show. “Whether we are doing things right or wrong … the fact that there’s a constituency and a large percent on one side of the aisle that feels that we’re not transparent, that feels that we’re not communicating properly, that feels that things are not being done the way they should be done, is a communication problem on our side. We have our jobs cut out.”

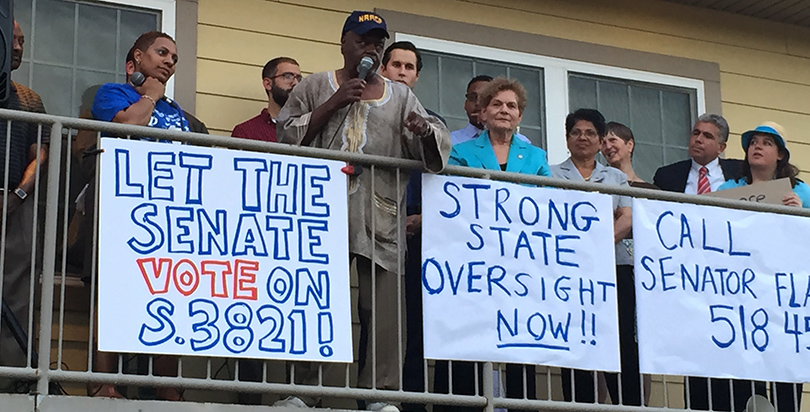

Hundreds of East Ramapo parents, students and community leaders marched through the streets of Spring Valley, N.Y., June 22 to rally support for state oversight of the troubled school district as the legislative session wound down for the year. The state Assembly passed the bill but it failed in the Senate. (Photo: Mareesa Nicosia)

Assemblyman Kenneth Zebrowski, who co-sponsored the oversight bill with Assemblywoman Ellen Jaffee, is calling on the state Education Department to use its statutory power to do at least some of what the failed bill would have. He wants state officials to appoint an interim monitor, who would have limited authority but would be a day-to-day presence and assist with improving community relations between the board and the public. He also wants the Comptroller’s office to conduct a forensic audit.

“We have a major problem here,” he said. “This is something that has been studied ad nauseum and (we need) to protect the educational opportunities of these kids. It has nothing to do with any one group or religion.

“New York is going to have to figure out how we deal with this district and any similar districts that could be in a similar situation in the future.”

New York City resident Andrew Mandel, 37, a former East Ramapo student who heads the Strong East Ramapo group, has organized thousands of alumni, students, parents and neighbors — along with statewide and national advocacy groups — to the oversight cause in the last nine months. He sees progress despite the bill’s failure: More attention than ever is now focused on East Ramapo, he said. The New York Civil Liberties Union, American Jewish Committee and Anti-Defamation League endorsed the bill.

“The community is not going away in its push for change,” Mandel said. “This has reached a totally different fever pitch.”

Lead photo by Getty Images

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)