New Study: Two-Thirds of Teachers Censor Themselves Even When They Don’t Have To

Fear of parent backlash making educators limit class discussions of political and social issues even in states with no laws barring ‘divisive’ topics.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

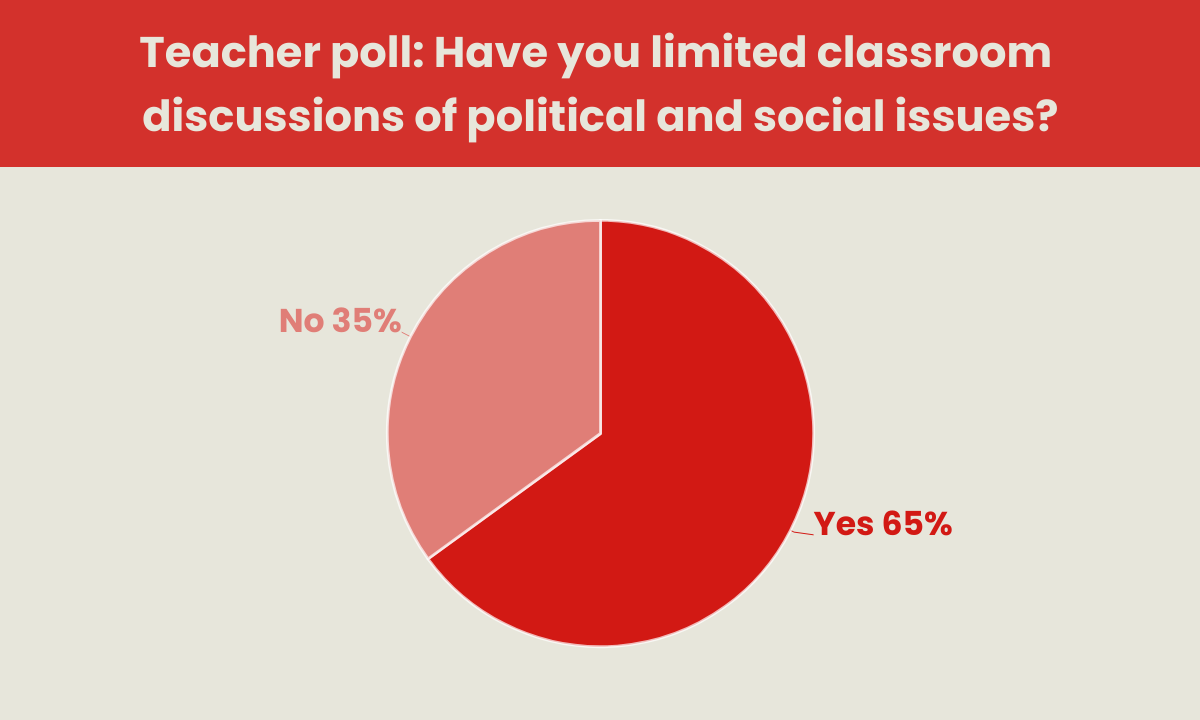

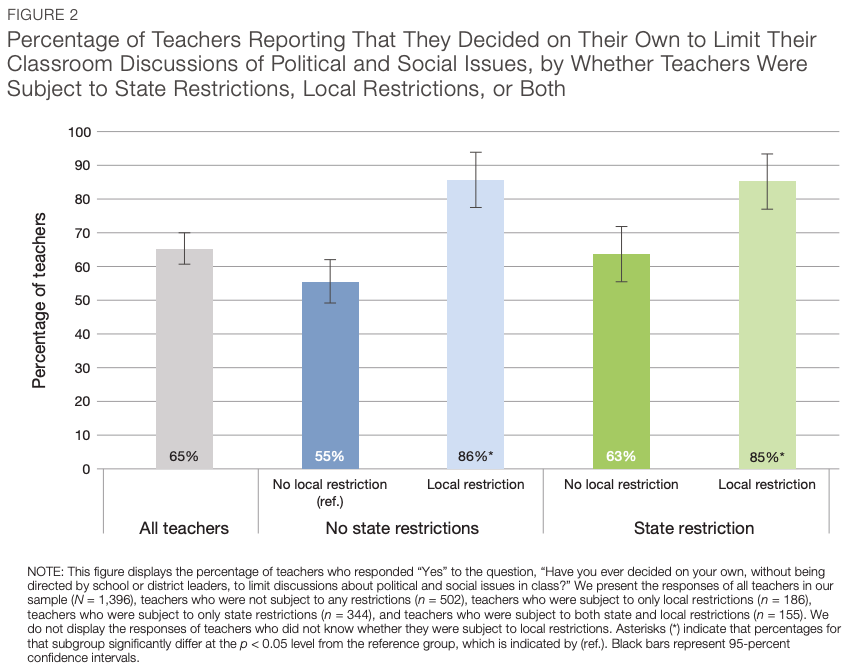

Two-thirds of U.S. teachers have limited discussions of political and social issues in their classrooms, even in places where there is no law or policy prohibiting instruction on race, gender identity, sexual orientation or other hot-button topics, according to a new survey conducted by the RAND Corp.

That means twice as many teachers as are legally barred from discussing what critics call “divisive concepts” have chosen to curtail their own classroom speech.

The finding marked the first time that researchers have quantified what the report describes as a “spillover effect” that causes educators to censor themselves even in communities that have typically supported such discussions, says Ashley Woo, one of the authors.

A key reason why educators engage in self-censorship, RAND found, is a concern that their instruction — legal or not — could trigger a parental backlash.

“Oftentimes, it’s a really mobilized, very vocal minority of parents in a community,” says Woo. “Not only can parents come up to you and have a verbal altercation, but there’s also this idea that they can threaten your reputation through social media, or that they might be able to go to your leaders and threaten your job. … Even the specter of that can create a lot of anxiety for teachers.”

More than a third of America’s 3 million teachers reside in one of the 18 states that adopted laws restricting educator speech regarding race, gender and LGBTQ people between April 2021 and January 2023. But because some are subject to local policies or edicts prohibiting instruction about certain topics, half teach under some type of restriction.

Teachers in states that don’t have the laws are just as likely as those that do to say that they are subject to school- or district-level restrictions, the survey found. Some have stopped discussing controversial topics not covered by statutes or policies, such as abortion rights or climate change. Unsure what exactly has been outlawed, others report deciding not to discuss historical figures of color or civil rights.

Fifty-five percent of teachers who aren’t governed by any state or local limits on speech decided to change their instruction anyhow. Educators who don’t face formal speech constraints but live in conservative communities were more likely to choose not to address social and political topics. About 40% of educators in politically liberal places where no restriction exists reported curtailing their instruction.

“Those are the kinds of communities where probably parents actually want and support those kinds of conversations in the classroom,” says Woo. “These are not voters who voted for the leaders who are putting these kinds of policies in place. These are not communities that want these restrictions in place.”

The survey’s findings jibe with recent research from the free speech organization PEN America estimating that laws the organization deems “educational gag orders” affect 1.3 million K-12 teachers and millions of students. The “spillover effect,” RAND notes, means the number impacted is actually much higher.

The data is drawn from RAND’s 2023 State of the American Teacher Survey, administered to a nationally representative sample of 1,439 K-12 teachers in January and February 2023. Communities’ political leanings were gauged by voting patterns in the counties where respondents live.

Regardless of why individual teachers choose to alter their curriculum or other features of their instruction, top factors cited include fear of angering parents, a lack of guidance or perceived support from school administrators and concerns they might lose their jobs or licenses. Some of those surveyed mentioned hearing that educators elsewhere had been disciplined for engaging in controversial discussions.

Local guidance to teachers sometimes comes in the form of a policy, but often it’s an admonition from a principal: “More implicit than maybe like a formal policy, but it’s still a message that teachers are receiving from their local leaders,” says Woo. “Teachers may take that and be, like, ‘Okay, well, I guess I shouldn’t be talking about that, then.’ ”

Across the board, 49% named concern that higher-ups would not support them if parents complained as one of their top three reasons for deciding to self-censor. Some teachers said school or district leaders had told them to avoid certain topics because of community pressure, while others said they had received little or no guidance.

Proponents of restrictive laws say parents need more control over what their children are exposed to in school and that discussion of “divisive concepts” pressures students to adhere to an ideology and tramples free-speech rights of those who disagree. Polling has consistently found scant support for limiting instruction about race but disagreement about whether and at what age students should learn about LGBTQ history.

In many communities in states where there is little political support for curtailing instruction, protesters have brought school board meetings to a halt and threatened to root out educators and curricula aimed at “indoctrination.” Record numbers of board members and other district leaders have quit as a result of harassment.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)