New Study: Many Older Students Struggle to Push Beyond Reading ‘Threshold’

To comprehend what they’re reading, many middle and high school students still need decoding support, researchers say.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Mara Mitchell long suspected her oldest son C.J. just skimmed over books without really comprehending what he was reading. But she didn’t grasp how poor his skills were until he sat down a couple years ago to read a simple book to his little brother.

After he um’d and uh’d his way through a picture book about starting kindergarten, “My youngest said, ‘Mama, C.J. can’t read,’ ” Mitchell said. “Somewhere a ball had been dropped, and as much as I’ve been trying to be an advocate for him, something was missed.”

Now in ninth grade at Whites Creek High School in Nashville, C.J. is among many teens who lack the skills to sound out and understand challenging vocabulary. In class, he often struggles to pronounce longer words.

“When I get to them, I’ll stop, and I’ll wait on the teacher to say it,” he said. In middle school, he was determined to figure out words on his own because teachers told him it would only get harder in high school.

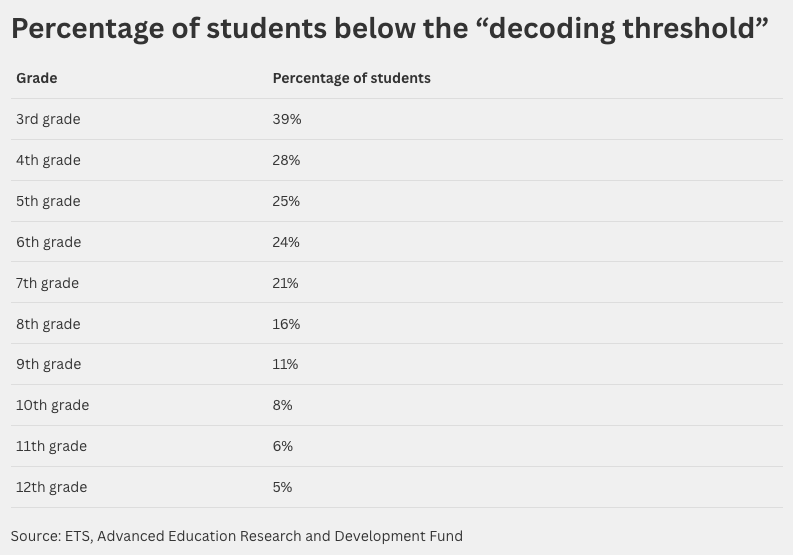

New research shows older students like C.J. hit a “decoding threshold.” Over 20% of students in fifth through seventh grade stumble over words they don’t recognize or can’t sound out, often preventing them from grasping the main idea of reading materials for school, according to the study released Wednesday from the Educational Testing Service and the Advanced Education Research and Development Fund.

Falling literacy rates following the pandemic have drawn more attention to adolescents’ reading proficiency. National tests from 2022 showed alarming declines in eighth graders’ reading skills.

But experts have long recognized that many older students lack a strong foundation in reading. “A lot of kids could very well have their basic K-2 foundational skills down pat, but they still need decoding support,” said Rebecca Sutherland, a co-author of the report and the associate director of research for Reading Reimagined, a project of the research and development fund. “There’s an assumption … that kids can self-teach.”

A nationwide push to strengthen students’ reading performance has centered on the early grades. Over the past decade, nearly 40 states have enacted legislation calling for research-backed reading instruction that emphasizes phonics. Sutherland said the new data points toward the need for a similar agenda for older readers.

The report on over 167,000 students in grades three through 12 is based on the results of a screening assessment called ReadBasix, developed by ETS. The project was inspired by a landmark 2019 study showing that students who fall below the decoding threshold struggle to comprehend material as it grows more complex and abstract in the higher grades.

“If decoding a sentence is consuming all of your cognitive capacity, then you’re not going to have anything left for comprehension,” Sutherland said.

As an example of how students’ skills drop off as they reach the upper elementary and middle grades, she said those who can easily read “tree” or “tricky” have no problem with similar one- or two-syllable words. But when they encounter words that don’t follow typical patterns — like “tripartite” in an American government class — those skills don’t necessarily transfer.

The findings don’t explain why students fail to transition to more challenging vocabulary. C.J., for example, wasn’t diagnosed with dyslexia until fifth grade. Others may have been in a school with a “whole language” approach to early literacy that didn’t emphasize phonics.

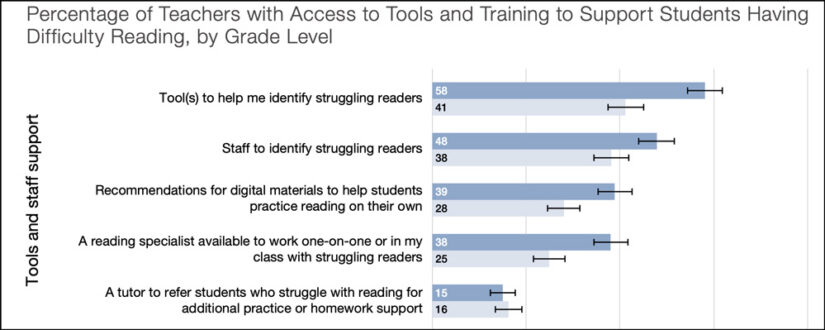

The study sheds light on why upper elementary and middle school teachers estimate that 44% of their students frequently struggle to read materials for class — a top finding from a recent survey Sutherland conducted with the Rand Corp.

Almost three-quarters of the roughly 1,500 teachers who responded said they need more resources to identify and support students with reading problems. The conundrum is that middle and high school educators, who strive to be subject matter experts, don’t spend much time on basic reading skills, and state standards typically don’t expect them to.

“The demands on teachers are enormous, and the preparation is so minimal,” said Julie Burtscher Brown, a literacy specialist for the Mountain Views Supervisory Union in Woodstock, Vermont. “In the higher grades, students can be multiple years apart, sitting together in one class.”

She’s part of a steering committee leading the new Project for Adolescent Literacy, which will release the results of its own teacher survey next month.

Brown led a course to introduce teachers in her own 1,000-student district to some of those practices.

“We had AP Physics teachers learning alongside preschool teachers. It was really quite special,” she said. The course covered, for example, how studying the structure and origin of words in class can contribute to comprehension. Brown urged teachers to give all students the opportunity to write and read aloud throughout the day. “So many students need support reading multisyllabic words accurately, and we’re not going to do that with picture books.”

Avoidance strategies

As students get older, their struggles with reading often show up in disruptive behavior or a pattern of avoidance in class.

“When it’s time to read, they have to go to the bathroom,” said Christina Cover, a special education teacher in the Bronx, New York, and a member of the steering committee for the Project for Adolescent Literacy. “They might sit there and refuse to read, refuse to discuss. Everybody else is annotating their books with tons of sticky notes.”

But in middle and especially high school, teachers often think it’s not their responsibility to spend time on the basics. Many are already assigning excerpts of books instead of full chapters.

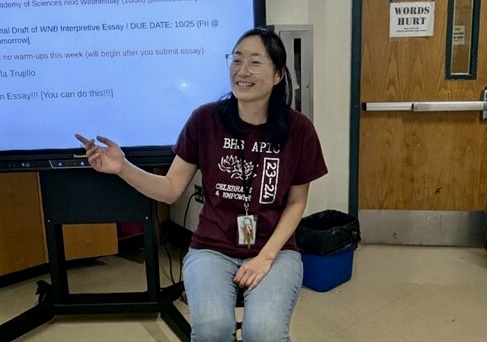

Diane Kung teaches an honors English class at Berkeley High School in California and another course focused on Asian American-Pacific Islander literature. Her students are working on “big projects” based on nearly college-level texts dealing with race and bias.

“With basic vocabulary, you assume that most kids will just know it or look it up,” she said. The school, she said, also has a “vast network of support,” including case managers for special education students and afterschool programs for low-income students.

Her views on what classroom teachers should do for students who lack strong reading skills have shifted over time. Last year, she taught a small intervention class for English learners that allowed for “deep diving” into fundamentals and basic grammar. She plans to offer warm-up vocabulary exercises in her other classes to help students who might need extra support.

She also has a 7-year-old daughter who is learning to read.

“As I watch her develop, I’m thinking about my own students who are 14, 15, 16,” she said. “I’m like, ‘Oh, maybe this is what they missed when they were her age.’ ”

New ‘frontiers’

That’s why Sutherland recommends that districts extend screening to students in later grades. ReadBasix, offered by Buffalo-based Capti, starts at $500 a year for multiple licenses. Stanford University developed the Rapid Online Assessment of Reading, or ROAR, which is free.

Getting curriculum companies to offer foundational materials for students in the upper grades, like they do for younger readers, is the next step, experts say.

Curriculum designers “often make the assumption that students in upper grades have already mastered decoding,” said Eric Hirsch, executive director of EdReports, a nonprofit that reviews how well curriculum follows Common Core standards.

While educators are directing more attention to older students’ reading challenges, parents who watched their children struggle during the pandemic have also brought the issue to the forefront.

“Suddenly you have a lot of families who are feeling super powerless, seeing their kids at home on screens and saying, ‘Oh my goodness. My child can’t access their education for a multitude of reasons,’ ” said Rachel Manandhar, a special education teacher who works with Kung at Berkeley High. “Literacy became paramount.”

Mitchell was one of those parents. She went through a literacy fellowship program this past summer offered by Nashville PROPEL, a parent advocacy group. The experience, she said, boosted her confidence when asking teachers about the services C.J receives at school and opened her eyes to his reading problems.

“This is why work was not being completed,” she said. “He can’t do it on his own because he doesn’t understand what he’s being asked to do.”

At school, almost every assignment includes reading material. In a wellness class, he recently had to answer questions based on articles about video games, stress and mental health.

Mitchell has always signed C.J. up for tutoring at school, but now someone also works with him specifically on reading skills. PROPEL connected Mitchell with a specialist that hemeets with virtually once a week. Together they’ve been reading “Clean Getaway,” a middle school-level book in which an 11-year-old learns about racial history in the South while taking a road trip with his grandmother. C.J. said it’s the type of book he wants to be able to read independently.

“I struggle doing it on my own,” he said. “I try it a little, and then I come home to get help.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)