A ‘National Teacher Shortage’? New Research Reveals Vastly Different Realities Between States & Regions

First national comparison of unfilled, full-time teacher roles shows that nine states are experiencing high vacancy rates

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A new report casts doubt on the narrative of a widespread “national teacher shortage,” finding instead that thousands of vacancies appear to be localized so far in nine states across the country.

Mapping the vacancies nationally, a recently published working paper and website crafted by three education researchers offers the latest, though incomplete, snapshot of reported teacher shortages.

The data suggest the pandemic has exacerbated shortages in specific teaching areas and some states that have faced persistent and well-documented shortages for years, creating a patchwork of different education realities in the United States that vary from district to district and across state lines.

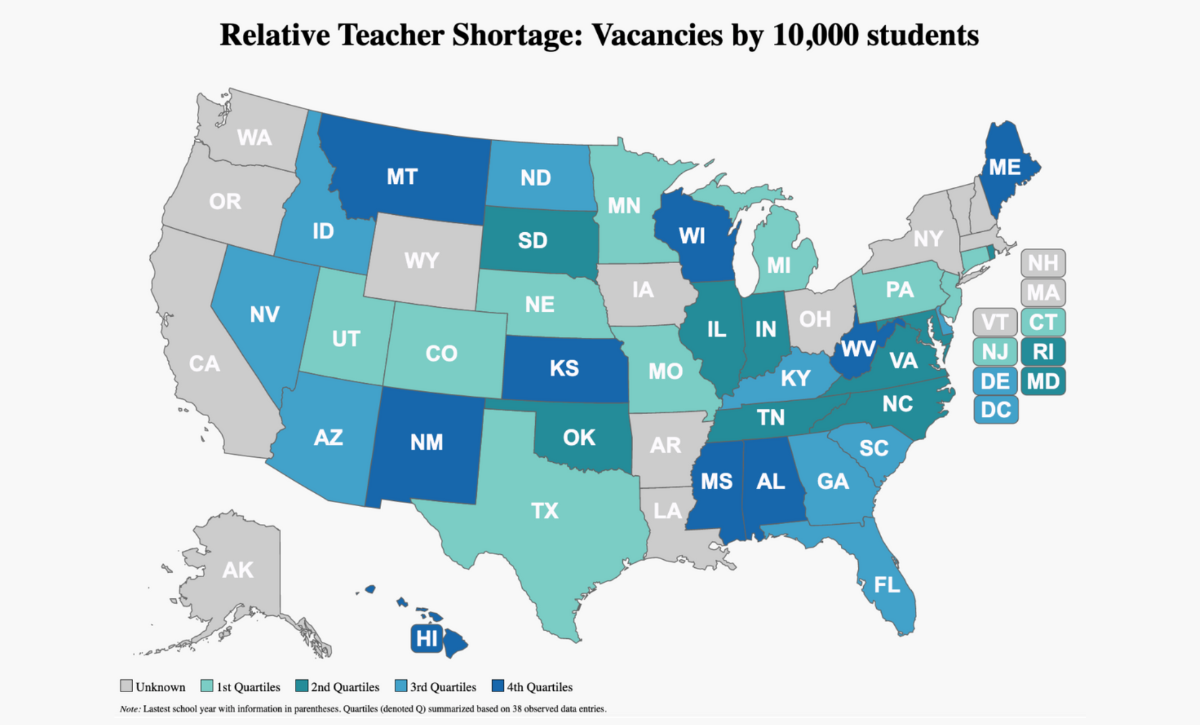

Of the nine states where vacancy rates are highest, Mississippi faced the highest vacancy rates, with 68 missing teachers per 10,000 students for the 2021-22 school year. In contrast, Utah’s vacancy rate was less than 1 per 10,000 students. The report does not yet compare these rates over time, because of differences in state data reporting and urgency to understand the most up-to-date vacancies.

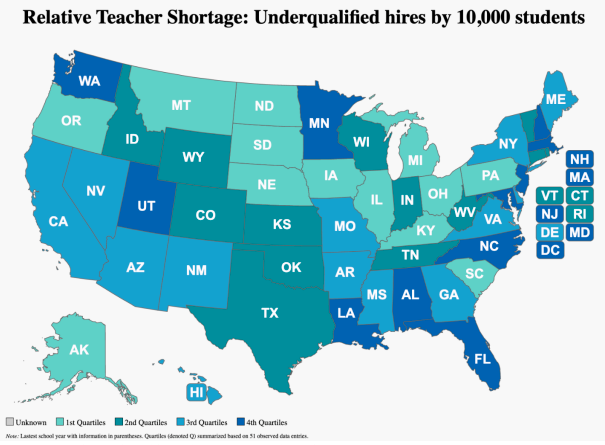

The report also identified another critical issue: Currently there are 163,650 “underqualified” educators — about 5% of the force nationally — teaching without certification or outside of their subject area. More state-level data is available for this group, showing the number of “underqualified” teachers in some states exceeds 20,000, which has risen in the last several years.

“There are substantial vacant teacher positions in the United States. And for some states, this is much higher than for other states…. It’s just a question of how severe it is,” said Tuan Nguyen, lead author on the working paper and education researcher at Kansas State University. “The pandemic has just exacerbated the situation that was already starting to build up…just made it worse for some states.”

Nationally, an estimated 36,504 full-time teacher positions are unfilled, with the number potentially as high as 52,800, the report found.

The vacancy estimates from Nguyen and co-authors Chanh Lam and Paul Bruno are significantly lower than the 300,000 reported by the National Education Association and national media (the higher estimate includes non-teaching staff such as bus drivers and school counselors). They join a host of academics attempting to make sense of shortages in the absence of federal data systems, which would put vacancies, which vary school to school and district to district, into context.

Published with the Annenberg Institute for Education Reform at Brown University, the report raises concerns about teacher education program pipelines; staffing historically hard-to-staff positions in rural areas, STEM and special education; and the lack of accurate data.

Their work marks the first time vacancy numbers have been documented for all 50 states and Washington, D.C. as reports flow in about districts shifting to four day work weeks, or calling in the national guard and former military to teach.

“A lot of the things that they’re doing right now seem to be a little, quick band-aid to stop the bleeding. But it’s not going to solve this long term issue, particularly for states that have persistent shortages like Kansas, Florida and Mississippi,” Nguyen told the 74.

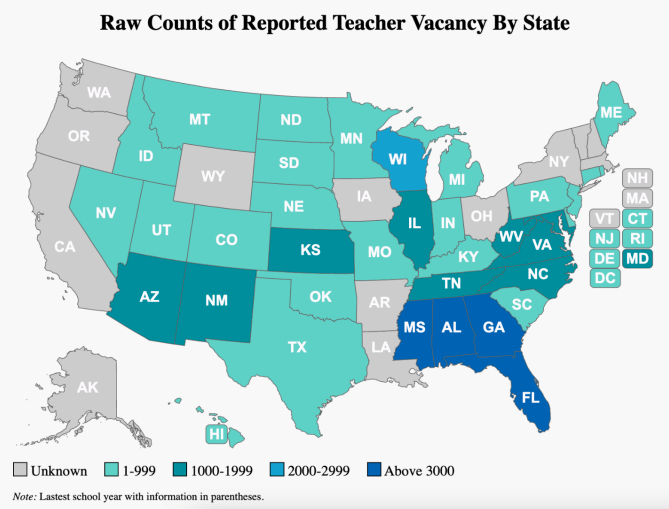

The highest raw numbers of open teaching positions are concentrated in the south and lower Atlantic, where about 22,000 positions are open, triple the picture in midwestern states. Alabama, which had over 3,000 vacancies in 2021-22, sits in stark contrast to Illinois, where 1,703 positions were left unfilled.

Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi also experienced high raw number of vacancies in the 2021-22 school year, each missing at least 3,000 teachers.

Nguyen described vacancies and staffing challenges as “ubiquitous,” but constituting a huge range. Beyond the nine states facing highest vacancy rates, another 19 have modest shortages, between 0 and 12 vacant positions per 10,000 students. Nine others face moderate shortages, missing between 12 and 15 educators comparatively. 13 states did not share complete data and could not be compared, the researchers found.

Estimates are conservative. Not all districts provided vacancy data to their state agency. And while some states include “underqualified” teachers in their definitions of vacancy, Nguyen and coauthors only considered unfilled positions in their final tally, relying on state and federal education data along with news stories.

Factors driving vacancies

Thousands of open posts does not mean that teachers left the classroom in droves during the pandemic, researchers at Rand, Kansas State University and Brown University told The 74.

Rather, three trends are unfolding simultaneously: teacher preparation programs face declining enrollment; respect for and interest in teaching has plummeted; and most districts expanded hiring beyond pre-pandemic numbers with federal relief aid.

“It’s only in this year two, and really, in year three [of the pandemic] that we’ve seen an uptick in turnover, but nothing like a mass exodus, the attrition that we were concerned about,” Nguyen said. “The teacher supply pipeline seems to be stagnating or decreasing over time. Over the last 10 years or so there has been a substantial drop in the number of teacher candidates.”

Concerns about public disrespect, low wages and legislation restricting classroom content may help explain some of the pipeline challenges and high vacancies particularly in southern states, Nguyen hypothesized.

“There’s also been increased attention to what it means to be a teacher…particularly about what teachers can or cannot teach in the state; whether or not social emotional learning is an important issue that we need to teach; how teachers may not teach anything about racism in America,” Nguyen said.

“It’s like, hey, there are these multitude of factors that are overlapping each other,” he said, “and they seem to be concentrated in the South.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)