New Report Raises ‘Cautionary Flag’ on Schools With High Numbers of Students in Credit Recovery Programs, Calls for Greater Accountability

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

It was a good-news story gone horribly wrong. Located in a low-income neighborhood in Washington, D.C., Ballou High School was lauded in 2017 for rapidly improving its graduation rate. For the first time, every senior who graduated from the school was accepted to college.

Then, the investigations hit. In January, Washington’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education found that about two-thirds of Ballou seniors who were awarded diplomas hadn’t earned them. Among the policy violations driving the graduation spike was the inappropriate use of credit recovery courses, which are designed to give students a second chance to pass required coursework. But many students at Ballou, investigators found, enrolled in credit recovery even before they failed the original course.

In a new report by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, researchers point to the D.C. scandal as an example of how credit recovery programs can go wrong. With a skeptical eye on the courses — in particular, the computer-based variety — the report found credit recovery is widespread, with schools that serve the country’s most at-risk youth relying on it the most.

While much remains unknown about the efficacy of such courses, the report offers new detail about their proliferation: About 69 percent of high schools nationwide reported enrolling at least one student in them during the 2015-16 school year, according to the report. Of those schools, more than 8 percent of students were enrolled in at least one credit recovery course.

Fordham, a right-leaning education think tank, relies on recently released data from the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights, which first collected school-level stats on credit recovery during the 2015-16 school year. Fordham merged the data with federal student enrollment statistics to get a handle on the traits of participating schools.

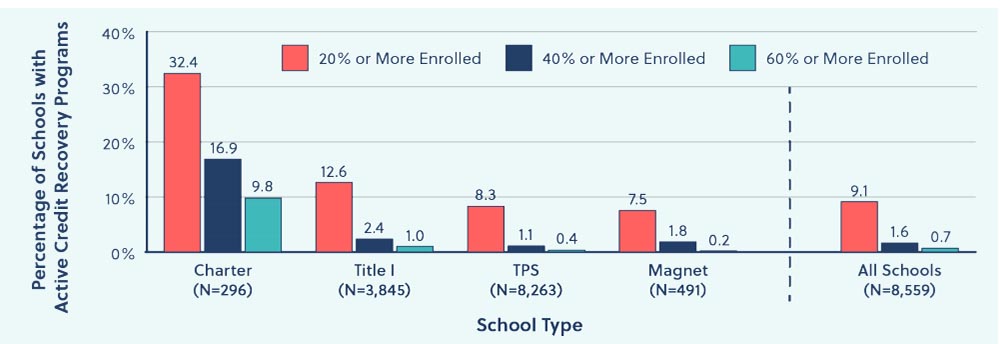

Perhaps most telling are Fordham’s findings on schools that enroll high percentages of students in credit recovery. More than 9 percent of schools with active credit recovery programs enrolled at least 20 percent of their students in the courses. Large enrollment in credit recovery, researchers note, could indicate abuse.

The report cautions painting all credit recovery programs with too broad a brush, but Fordham argues that “it is past time to wave a cautionary flag” when half or more of a district’s students are enrolled in such courses.

“While some of these programs might be really good, we know that some of the online programs, anecdotally, are really bad,” said Adam Tyner, Fordham’s associate director of research and a co-author of the report. Because the report found a large share of students in credit recovery, he said, “it seems like a lot of students are getting exposed to potentially low-quality coursework.”

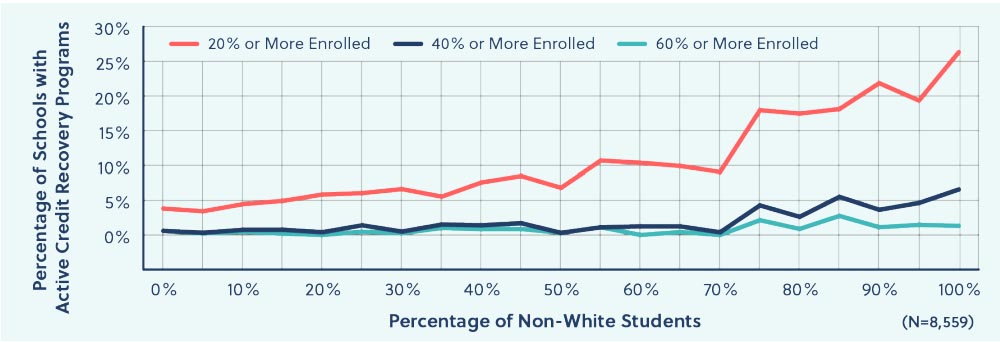

Urban schools are most likely to enroll high percentages of students in credit recovery, as are schools with large shares of low-income students or children of color. Among urban high schools, about 17 percent enroll at least 20 percent of their students in credit recovery — a rate more than double that of schools in suburbs and rural areas.

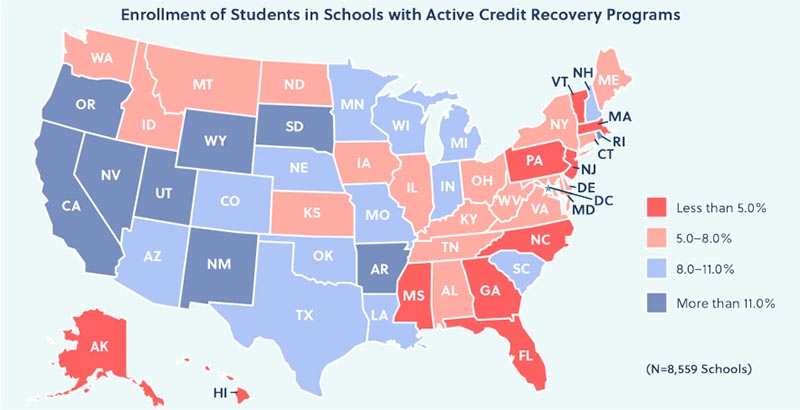

On the state level, schools in Rhode Island, Nevada, New Mexico, California, and Washington, D.C., enroll the greatest share of students in credit recovery, the report found. Regionally, western states are most likely to enroll large shares of students in such programs.

Charter schools are far less likely to have credit recovery programs than traditional public schools, Fordham found. However, charters that do offer the courses are far more likely to enroll large shares of their students in them.

In Washington, D.C., schools were more likely than the national average to offer credit recovery; among those with active programs, nearly 13 percent of students participated. D.C. schools with credit recovery were also more than twice as likely as the national average to enroll more than 20 percent of students in the programs, and schools with more students of color had higher participation rates than the city’s whiter schools.

Following the investigation in D.C., the city’s credit recovery program was put on temporary hold as the district rewrote policies governing the courses, said Sarah Navarro, the district’s deputy chief of graduation excellence. Those courses resumed earlier this month.

“We think that credit recovery is a very important way to allow students to have a second chance, but we’re also committed to making sure that it is equally as rigorous as the original course,” Navarro said. “We have some safeguards in place to make sure that students really do have content mastery of that material before they pass the class.”

Although the Fordham report offers new information on the types of schools that participate in credit recovery, Tyner acknowledged it raises more questions than it can answer. For example, the data do not distinguish between types of credit recovery programs — including whether the courses are offered online or through classroom instruction — or the quality of the offerings. The report also does not attempt to explain the enrollment differences observed between states, school types, or student populations.

But it adds to a growing body of research that, along with news reports, raises questions about the proliferation of credit recovery.

A recent report by the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, found that schools that rely most on credit recovery saw large increases in graduation rates even as their students performed poorly on state tests.

A 2016 report found some troubling short-term results on Chicago’s online credit recovery program. That report, conducted by the nonpartisan American Institutes for Research, was the first major study on online credit recovery and focused on students who failed Algebra I and needed to make up the credit. Students who enrolled in online courses, researchers found, had lower pass rates and scored worse on end-of-course tests than students in traditional classrooms. Students enrolled in the online class also considered the course more difficult and ended with less confidence in math.

Long-term effects, however, were less stark: Researchers found no difference between the two groups in terms of their likelihood of passing subsequent math classes or their ability to graduate.

Jessica Heppen, AIR’s vice president for research and evaluation and the lead author of its study, sees the potential of online credit recovery to benefit students. Such courses offer students an alternative learning method, are often interactive, and frequently provide immediate feedback. But Chicago students floundered in the courses, she said.

“It was a harder, more rigorous course than the face-to-face class,” which could be beneficial if the aim of the district is to “increase students’ exposure to rigorous, high-quality content,” she said. “But it didn’t come with the promised, or hoped-for, supports, or a stopgap if kids really weren’t ready for that content.”

AIR is currently researching the efficacy of online credit recovery in Los Angeles, though results aren’t yet available. That study focuses on a credit recovery program in which students receive instruction through an online program but also receive classroom support.

While the Chicago study focused on an online credit recovery course that was well implemented, Heppen noted that some programs have been characterized as “credit farms where kids barely have to do anything” to pass. An investigation by Slate, for example, found that online credit recovery courses are often easy to game.

The Fordham report offers a handful of recommendations to help ensure the quality of such programs, including a push for states to collect better data.

Fordham also recommends that states create policies that mandate clear eligibility requirements, an evaluation process that vets the quality of online offerings, and audits when schools enroll high percentages of students in the programs. Currently, 12 states and D.C. have formal policies concerning credit recovery, according to Fordham, but few focus on quality.

Merely having a policy is not enough, Tyner said. Schools also need to be vigilant about enforcement.

“If Washington, D.C.’s state administration had looked into what was going on in any given school more closely, they would have seen that some of those policies weren’t being followed,” Tyner said. “Policy is important, but follow-through is important, too.”

Disclosure: The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the Doris & Donald Fisher Fund, the William E. Simon Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)