New Report Highlights Teacher Eval Paradox: High Ratings Across the Board, But Growing Backlash

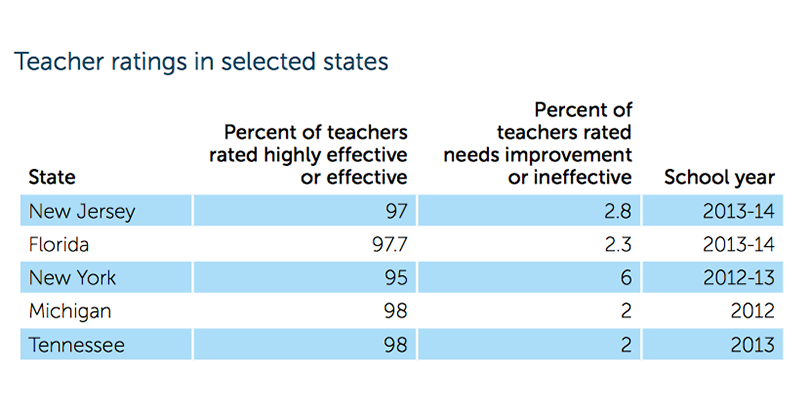

The vast majority of teachers are still getting high marks, even while most states have begun using student test scores in teacher evaluation at the urging of the Obama administration.

That’s according to the National Council for Teacher Quality, which just released the latest in a series of invaluable, deeply researched reports that document how states judge teachers and principals.

This research echoes recent reporting from The Seventy Four and elsewhere finding that under new evaluation systems, the overwhelming majority of teachers are deemed effective.

As the council, a nonprofit that focuses on improving teacher quality, puts it, “Some policymakers and reformers have naively assumed that because states and districts have adopted new evaluations — including those that put a much stronger emphasis on student outcomes — evaluation results will inevitably look much different. But that assumption continues to be proven incorrect.”

Photo: Courtesy National Council on Teacher Quality

The council has some suggestions for how to fix what seems to be score inflation, but it’s not clear how successful they will be. For example, the report recommends having multiple observers conduct evaluations of teachers, saying “the practice is associated with better differentiation” of teacher effectiveness.

It lauds New Jersey as among four states that require multiple observers — yet pages earlier highlights that 97 percent of Garden State teachers are deemed effective or highly effective.

The report criticizes the use of student learning objectives where teachers are scored based on whether students meet certain goals the teachers set themselves and which may or may not be approved by an evaluator, depending on the state. Turns out those student scores are “not very meaningful measures of teacher performance,” according to the report.

The council also doesn’t think teachers should be evaluated by school-wide scores, a common practice for teachers in traditionally non-tested grades, such as early elementary and high school, and subjects, such as music and social studies.

But without using these measures, it will be extremely difficult to evaluate all teachers based on student test scores — at least not without further contributing to concerns about over-testing.

Backlash from the testing component of teacher evaluation appears to be coming to a head, and the council acknowledges as much, chiding readers not to “forget why student assessment is so important.” Most people reading a report from the National Council for Teacher Quality will not forget, but they are also unlikely to be the same people driving the anti-testing movement.

In terms of policy solutions to these concerns, the report offers only, “Communicating why assessment and performance measures matter is a critical task where there is clearly more work to be done.”

At the heart of the move to tougher evaluations is a paradox: the new systems have not found many ineffective teachers, but have proven politically toxic. The worst of both worlds for reformers.

How this happened is unclear. One interpretation is that unions have cynically emphasized an imagined test-and-punish component of evaluation to pre-empt real accountability. The council’s view: “Teacher organizations may be shooting down assessment for their own interest, but we aren’t serving kids by rejecting assessment.”

Another interpretation is that teachers in schools genuinely felt that the stakes were high for a number reasons — including the firing-bad-teachers rhetoric surrounding evaluation and the inherent uncertainty of a completely new system. That unease may have spread to parents, students, and union leaders.

Incidentally, the report does recommend increasing the stakes for teacher evaluation — by encouraging states to label more teachers ineffective and tying results to important decisions — while at the same time hoping to quell the opt-out movement.

Good luck with that.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)