New Ideas for a New Era of Public Education: Moving Beyond a Portfolio of Schools to a Portfolio of Student Opportunities

This essay was originally published as part of CRPE’s 25th anniversary collection, Thinking Forward: New Ideas for a New Era of Public Education

For 25 years the Center on Reinventing Public Education has studied, informed, and refined new ideas for how public education can achieve its promise. We have posited and tested ways to allow families to choose educational settings that fit their needs and give educators the autonomy to create them, without losing sight of the public interest in schooling. We have focused on meeting the diverse needs of a community and continuously urged public officials across the country to do a better job meeting those needs. We envision an agile education system — one designed to innovate constantly, to improve continuously, to bend and stretch to meet the needs of every student.

We view public education as a shared objective, not a particular institution. We have sought ideas and evidence that balance student and family interests with public interests. In the years since our founding, our ideas have informed the transformation of school systems from New Orleans to Denver to the nation’s capital. Now there are signs the improvements in those cities are beginning to plateau. Across the country, every school system continues to struggle to meet the needs of the most complex learners and serve the students most deeply affected by trauma and generational poverty. There are also signs that the definition of an “effective” school must be revisited as we learn more about what best promotes child and adolescent learning, the limits of standardized testing, and the need for students to question and create, not just comply.

Meanwhile, the next generation appears poised to confront a multitude of challenges — from a changing climate to a changing economy — that will demand all of the talent it can muster. Education reformers everywhere are searching for new paths forward.

In the past, CRPE has started with a simple question — what makes schools coherent, effective, and innovative? — and worked outward to the implications for policy and governance. Starting with the student instead of the school leads us to important new places, especially as we contemplate lessons from the past and look to a future of great uncertainty. Amid all of that, there’s one North Star that runs through each of the essays in this collection: equipping each student for an uncertain future by broadening and customizing their opportunities for learning and growth.

The ideas we have presented in these essays are not intended to define a new school reform agenda or even a new CRPE agenda. We do not pretend to have all of the answers. The essays are meant to inspire new conversations and, perhaps, lay some groundwork for people from previously divided camps to come together around new ideas for the future. The challenges ahead are too important to be tied up in continuing conflict among different camps, advocates, and policymakers. Proposed solutions must be pressure-tested from diverse points of view. And they must ultimately be owned and operated by local communities.

We purposefully explored new territory and big ideas, but we do not mean to imply that school system leaders and policymakers should throw out their old to-do lists for implementing strategies that have proven effective. As we see it, the tenets that CRPE has always held — flexibility for educators, families empowered to make choices, attention to true equal opportunity, government assurances of quality, and true community engagement — are more essential than ever. But these strategies must evolve in ways that enable them to better meet the individual needs of students.

Imagine that 20 years from now, schools from the earliest grade level were highly customized, focused on early intervention, and cultivated students’ individual interests and talents. Schools would do whatever was required to serve the extremes, not the mean, so they capture talents that are now being lost and motivate many students who are now settling for mediocrity. This might mean that the role of some schools would be to serve as curators of services and supports rather than a single source providing everything to every student.

Schools teaching younger students would have outcome requirements focused only on a limited set of core gateway learning and developmental skills that were shown to be directly linked to readiness for secondary education. Older students could select or build personalized learning pathways toward careers by earning competency-based credits toward high school graduation, college coursework, and industry credentials.

Teachers would need to be of two kinds — those who build deep relationships with students and curate customized learning packages, and specialists who are experts at teaching specific bodies of knowledge. The former would be located in schools and the latter would often work in — or as — independent providers.

Schools would not be isolated; they would use learning experiences now locked up in community resources, such as businesses, hospitals and clinics, social service organizations, cultural institutions, and colleges.

Equity challenges in areas including gateway preparation and access to career pathways would be anticipated, especially for low-income and rural families. Attention to such challenges would be prioritized, not swept under the rug. Community “navigators” and other organizations would help support individuals and work to build connections, networks, and community.

Funding would increase, be more flexible, and follow students longer. A student who graduated early could use saved funds to come back to school for additional learning later in life. While still in school, a student developing a passion for dance could pay for specialized dance classes by forgoing another elective.

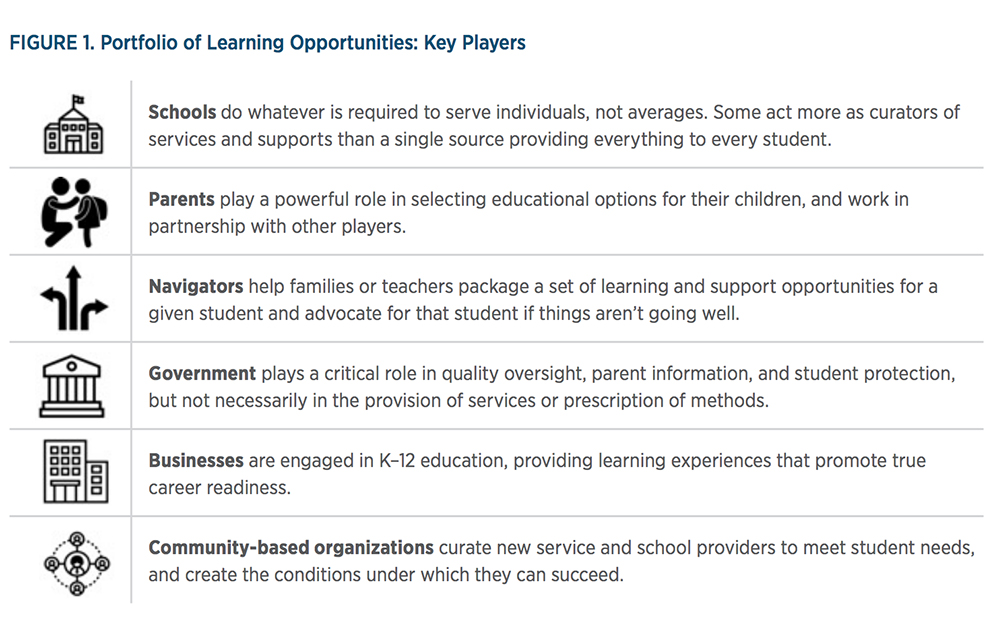

Government would play a critical role in quality oversight, parent information, and student protection, but not necessarily in the provision of services or the prescription of methods.

From unbundling to rebundling: Safeguards and enabling conditions

These essays show that a more customized, nimble learning system holds the potential to bring unprecedented opportunities to students facing complex needs, high poverty, and other vulnerabilities, but also that community-based attention, investment, and oversight are required to realize that potential. It’s not enough to unbundle. Thoughtful rebundling must happen and safeguards must be in place to ensure that a more agile learning environment doesn’t benefit only the most educated or advantaged families. If a primary goal of public education is social mobility, government and community actors must take steps to achieve that goal. Figure 1 outlines the ways key players could work toward a more nimble learning system.

Government should focus on ensuring a strong supply of not only school providers but also a wide range of industry, community, and service partnerships and providers. Accountability systems should move away from trying to drive improvement for the average student and instead focus on defining gateway competencies every student must master — literacy, numeracy, and basic knowledge of history, civics, and science. State standards are a workable starting point, but additional competencies can be incorporated into students’ individualized learning plans, including career-specific skills, advanced academic specialties, and accomplishments in domains such as technology or the arts.

Over the years we have written much about the importance of strong parent information as choices in a city increase. These essays demonstrate that whether it’s giving community providers an ability to make students and educators aware of their services, helping parents navigate the array of in- and out-of-school learning opportunities for their children, or helping students work with their advisers to set learning goals and find pathways to meet them, families will need no end of information.

Common enrollment systems and transparent, basic school performance data will continue to matter. But information systems must become more sophisticated to help ensure students and parents are able to discover potential learning experiences and make informed decisions about them. School system leaders should think through who is best equipped to provide this service: Should it be the district itself, or independent mediating organizations?

But while information guides and technology-enabled platforms are important, they are likely not enough. Families will need customized guidance, individualized to unique student needs and goals. Many of these essays suggest the need for “navigators” who can help families or teachers package a set of learning and support opportunities for a given student and who can advocate for that student if things are not going well. Individual consultants and nonprofit organizations could play this role. As implied above, some schools or charter management organizations could adapt to focus more on the navigation function than on providing all of those supports themselves.

The roles of community-based organizations may broaden beyond attracting new school operators and creating the conditions under which they can succeed. School districts, charter authorizers, and other school system leaders also will have to think about a broader suite of community assets, from academic enrichment opportunities to tutoring providers to social services. This will require coordination with businesses, higher education organizations, medical and social service providers, and other community organizations, all of whom have a stake in the K–12 education system but often operate in independent silos.

Transportation presents an important barrier to many families in decentralized systems of schools. It also presents a barrier to learning opportunities outside the school walls or normal school hours. School system leaders must think about new ways to move students to and from after-school tutoring, mental health appointments, and out-of-school enrichment experiences — or to bring those services to students where they are.

An unbundled education system presents risks of funding misappropriation. Auditing and oversight to protect against bad actors will remain important functions. Since some operators — such as career and technical education centers or online course providers — might have operations that span traditional jurisdictional boundaries, this might be an area where state governments have to ramp up their oversight functions.

Steps communities can take to get from here to there

We don’t claim to prescribe a precise outline for the public education system of the future. But we do highlight some priorities (improved career training, greater attention to the needs of students that school systems currently struggle to serve) and some important strategic elements (rethinking the career path and training program for teachers, tuning funding and accountability systems to the needs of individual students, ensuring more equitable access to out-of-school learning opportunities). For policymakers and practitioners looking to apply these broad concepts in a practical way, we offer some tangible starting points.

—Look at data. Which students are not getting what they need now? How can the system better flex to support their unique learning needs?

—Look at community. What learning opportunities exist outside the school system? Do all students have equal access? How can opportunities become more widely available?

—Look for gaps. What learning opportunities or supports do students need that don’t currently exist? Could accountability policies promote early identification and intervention strategies to prevent students from needing more intensive interventions later?

—Look at infrastructure. Do families have the information they need to find learning pathways that meet all their goals? What systems would allow them to access that information? Is transportation a barrier to learning opportunities? Could community-based navigators help low-income or otherwise disadvantaged families access social services and out-of-school learning opportunities? Could those activities be funded through specialized accounts and the outcomes tracked?

—Look at funding. Are the district and its schools capable of absorbing rapid changes in enrollment? Do they receive a level of funding for each student commensurate with that student’s individual needs? Are there specific funding streams, such as supplemental funding for special education or extracurricular programs, that could be doled out to individual students and placed in a “backpack”? Are there other funding streams, such as social service funding, that could also support students’ educational objectives, and that could be combined with education-specific funds?

—Look for innovators. Seek out and invest in truly innovative education proposals that will better meet the needs of students with leadership potential or other talents but who have other complex needs. Establish school design incubators for applying brain science to new school designs. Establish new teacher training programs for teachers who want to teach in these new school designs.

—Look across boundaries. Establish industry apprenticeship partnerships with associated competencies for triple-credit high school, college, and industry credentialing. Authorize charter and other autonomous schools that are designed to create innovative college prep plus career pathways. Create the regulatory flexibility to allow experimental schools to serve grades 9–14 or 9–16 and adult education. Promote microschools that specialize in excellent college prep curriculum. Allow funds saved on electives to be spent by families on individualized supports for students now or retraining later in life.

—Look for meaningful metrics. Shift accountability systems to focus on minimally time-consuming “gateway” assessments and more intensive improvement-focused site visits for schools that could most benefit from that support. Focus on parent information systems at the high school level.

Putting it all together

Conversations about the next generation of education reforms often get bogged down in either-or disputes. Should districts focus on improving their own schools or contracting with autonomous schools of choice? Can students gain access to job-related learning opportunities without having to sacrifice college prep high school coursework? Should states invest in expanding universal pre–K and other programs built to help lay students’ academic foundations, or should they focus on building K–12 schools capable of helping them achieve faster rates of academic growth?

An agile public education system would avoid pat answers to these questions and focus instead on providing effective, flexible, and individual pathways toward common goals. It would find ways to enable every student to achieve gateway competencies. It would also give every student the support necessary to achieve their full potential and allow them to pursue personal objectives such as job and language skills, social-emotional development, and achievements in science or the arts.

Most importantly, if something was not working, or a student’s needs were not being met, an agile education system would be equipped to change. A student-centered system would be animated by a drive to do whatever is necessary to prepare every student to solve the problems and capitalize on the opportunities that await the next generation.

CRPE has been positing and testing ideas about systems change for 25 years; we are not naive about the challenges implied by the ideas we propose. At its fullest realization, a student-centered education system brings many risks. Would greater individual gain necessarily mean less community good? Would the safeguards we propose be enough to protect those who are most vulnerable and close opportunity gaps? Would “reformers” repeat the mistakes of the past and advocate for policies that are not embedded in strong community-based constituencies? Would individualized career pathways and deeper industry partnerships track students or place too much career emphasis in schooling? How would existing schools and school districts cope with the disruptions and financial strain of more customization? Is the comprehensive American high school still relevant in the age of agility?

These proposals also imply a set of policy changes and system adaptations that are hard to imagine today. Some require cooperative agreements and collaborations among higher education, school districts, industry, and community service providers — entities that have not played well together. They imply major shifts in how we train educators, and perhaps in their labor contracts. There are potentially many new costs implied throughout, despite many options for redistributing funding.

These are not easy questions, but we think they are worth taking on for the simple reason that we do not see a way for education to prepare students to solve the problems of today, much less the future, given the fundamentally rigid and inequitable structures we have built in the past. Now is the time for all of us to fully engage in new visions, to form new alliances, and to commit to ongoing questioning and clear-eyed assessment. We hope these essays contribute toward those ends.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)