New Florida Study Suggests Public School Students See Some Benefits From Expansion of Private School Vouchers

A new study suggests that public schools can benefit from private school vouchers — programs that use public funds to send students to private schools.

Debates about vouchers tend to revolve around two major questions: How do these programs affect students who are given vouchers, and what happens to the students who remain in public schools?

Researchers analyzing the nation’s largest state-based voucher program, the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program, sought to tackle the latter, and they found that public schools generally benefit from the added competition. Florida’s program enrolls 4 percent of the state’s K-12 student population.

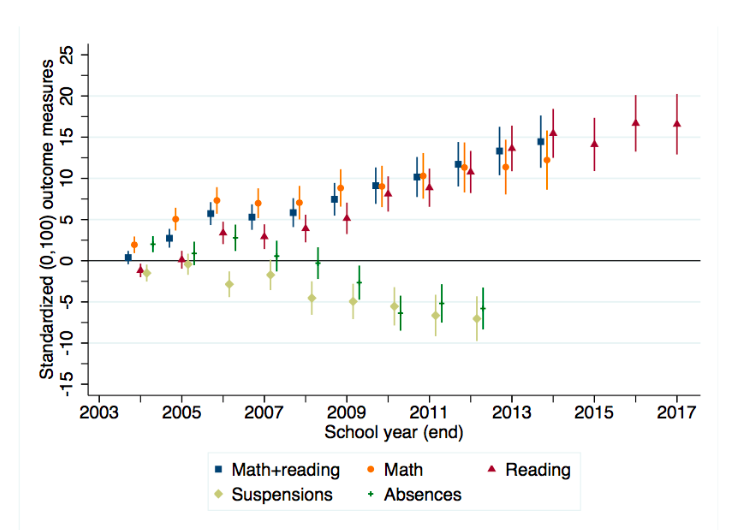

The findings show that as the voucher program expands across the state, public school students in areas with a larger share of private schools score higher on standardized tests and experience fewer suspensions and absences compared with public school students in areas with fewer private school options. The test score gains associated with a doubling in size of the state program were similar to the difference in impact on student achievement between a novice teacher and a teacher with a year of experience, explained Cassandra Hart, an associate professor of education at the University of California, Davis, and one of the co-authors of the study.

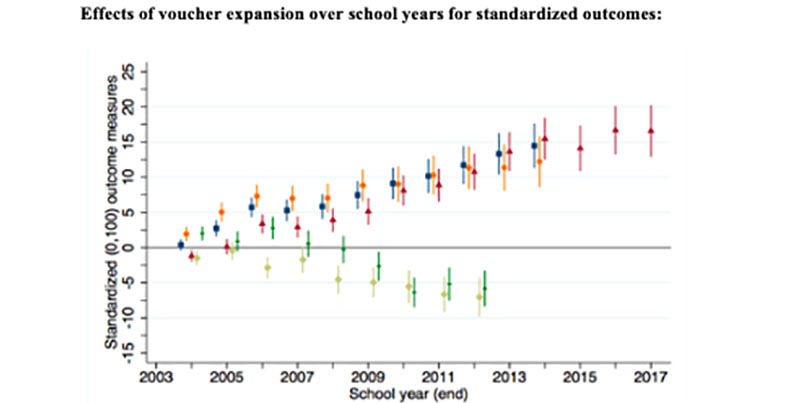

Effects of voucher expansion over school years for standardized outcomes:

The Florida scholarship program has grown considerably since its inception. In the 2002-03 academic year, the program spent $50 million on 15,585 students. By 2017-18, the program had grown to 108,000 students at a cost of $640 million. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has pushed for federal dollars to go toward these voucher programs, a broad term that generally captures any public money that goes toward subsidizing private K-12 school attendance. In Florida, the program gives tax credits to companies that donate to nonprofits that use the money to give scholarships to low-income students to attend private schools.

More than half of U.S. states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico had voucher or scholarship programs in place, according to EdChoice.

“I think one of the big policy considerations over these types of programs is that most students are going to be affected by them based on how they affect public schools,” Hart said. And what the study shows “pretty consistently is that public school students don’t seem in our data to be hurt by this program.”

The study examined student data on about 1.2 million unique students in the 2002-03 to 2016-17 academic years.

Key to the study is private-school density. Public schools benefit the most in terms of student test scores if they are close to private schools where students receive this voucher money and are in an area where there are many such private schools.

The kinds of students who benefit vary as well. By matching Florida birth and school records, the researchers were able to show that “the public-school students most positively affected by increased exposure to private school choice are comparatively low-socioeconomic status students,” which the study defines as lower maternal education levels and lower family incomes. Students from families with higher socioeconomic status had smaller but still statistically significant gains, the study said.

The overall findings didn’t surprise Hart because other studies have shown that competition has positive short-term effects on public school students. This study’s contribution to the literature, Hart said, is the analysis of a choice program’s long-term impact on public school students. Conceptually, it’s possible that as public schools become more used to competitive pressure through voucher programs, the impact of that competitive pressure could wane. Instead, the study shows evidence that as the Florida program grew, public school students experienced increasing gains.

Hart would like to explore other types of competitive pressure on public schools in subsequent research, such as from charter schools or magnet programs. Just because a program shows a positive impact on public school students, Hart said, it’s not necessarily the case that it’s the most positive intervention.

“I think it’s an open question whether other types of competition would produce similar or potentially greater” or lower levels of benefits, Hart said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)