Nearly a Third of North Carolina Child Care Providers to Close Within Months

Adequate funding could keep programs in operation when pandemic-era stabilization funding runs out at the end of June.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Members of the Joint Legislative Oversight Committee on Health and Human Services received an update on child care at their meeting April 2.

The biggest child care issue across North Carolina is the lack of sufficient funding to support competitive, family-sustaining wages for early childhood educators. Adequate funding could keep programs in operation when pandemic-era stabilization funding runs out at the end of June 2024.

‘Let’s be buffaloes’

Sandy Weathersbee, the owner of Providence Preparatory School in Charlotte, who also serves on the boards of the North Carolina Partnership for Children and the Child Care Services Association, shared his concerns with the committee.

Weathersbee’s primary concern is staffing. Early childhood education programs like his have to compete for teachers with the public school system, which has the advantage of offering state-funded health and retirement benefits despite low teacher salaries.

“We’ve not been able to find a solution to a problem that is bigger than we are,” Weathersbee said. “We need help.”

He argued that help is needed urgently because of the upcoming expiration of funding that stabilized early childhood education during the pandemic. That funding will sunset in North Carolina at the end of June 2024 — the date referred to as the “funding cliff.”

Weathersbee pointed to the recent results of a child care provider survey conducted by the North Carolina Child Care Resource & Referral (CCR&R) Council to bolster his argument that support is needed now.

Here are some key findings from that survey about the challenges providers expect to face when we reach the funding cliff:

- About 3 in 10 programs (29%) expect to close.

- About 4 in 10 centers (41%) expect to close or combine classrooms, leading to decreased enrollment capacity.

- More than half of programs (54%) plan to cut costs, which could reduce program quality, including child nutrition.

- Almost all programs (88%) expect to increase parent fees in the second half of the year, raising the annual costs for families by more than $1,000 per year.

- When asked to name one support that would help programs be sustainable, the most common response was increasing funds for staff salaries (38%).

With these storm clouds brewing, Weathersbee asked members: “Do we want to be cows or buffaloes?”

“Cows will try to outrun a storm only to succumb to its speed and stay in it longer. Buffaloes will run right into the storm and get out of it faster,” Weathersbee explained. “Let’s be buffaloes.”

‘We know what quality looks like’

Ariel Ford, director of the Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE) at the state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), provided the committee with updates on the state’s efforts to revise our quality rating and improvement system (QRIS), in addition to addressing the challenges posed by the funding cliff.

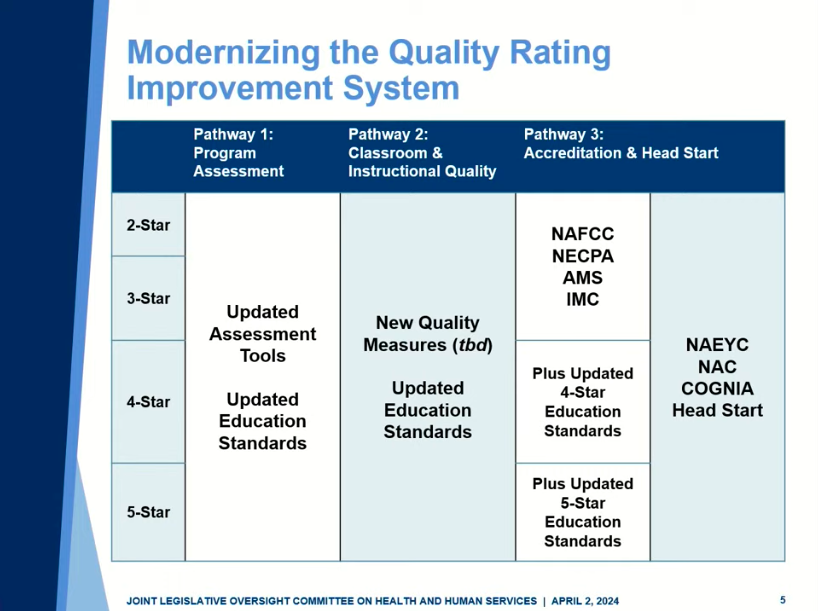

In 2023, the General Assembly passed legislation requiring the North Carolina Child Care Commission to make recommendations for updating the QRIS. This is the system through which child care programs are granted a rating of one to five stars based on meeting specific standards related to quality.

Ford pointed out that North Carolina was the first state to launch a quality star-rating system, back in 1999.

“What we’ve learned over 25 years is that we know what quality looks like, and we know that there’s multiple paths to get there,” Ford said.

Ford presented an overview of the commission’s recommendation to adopt three pathways to quality instead of the single pathway we’ve always had.

The first would be a modified version of the one that’s currently in place, in which programs are evaluated by an outside consultant and rated on a scale. The commission plans to review that scale if the new recommended pathways are supported by legislators.

The second pathway would be a new one specifically for programs that fall outside of the typical early childhood education framework, such as developmental day programs that serve children with disabilities.

“So for instance, if you have multiple children in wheelchairs that are feeding with feeding tubes, their day just looks a little bit different than our more traditional child care programs, and we wanted to honor that and to respect the quality that comes with that,” Ford said.

The third pathway is what Ford described as “shovel-ready” or “mission-ready” — a system for recognizing federal accreditations in our state’s star-rating system.

Right now, programs such as Head Start, Early Head Start, and those accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) have to go through the entire QRIS process for North Carolina, creating administrative redundancies and inefficiencies.

At the direction of the legislature, the commission created a crosswalk that aligns federal accreditations with our state’s rating system to relieve the administrative burden of these established high-quality programs.

Ford said the commission has this pathway ready to be implemented at the General Assembly’s discretion: “We can basically just turn that light on at any second.”

But looming over these potential changes is the June 2024 funding cliff. Ford also referenced the new survey results from the CCR&R Council, pointing out that North Carolina has already had a net loss of 53 programs in 2023.

Here are what some survey respondents in rural regions had to say about what they’ll do when the stabilization funding sunsets:

- “Childcare teachers have historically been one of the lowest compensated workers in our county. With the end of the staff bonuses we no longer have any incentive to offer teachers to stay except for their unending love of the children in their care. Unfortunately, that isn’t enough because their loving hearts do not pay the bills.”

- “I don’t know. This 4 years have beaten me up and I’m tired. We are taking the same surveys and SCREAMING that we are going under, and no one is listening. It’s disheartening.”

One intervention Ford proposed was the need to increase the subsidy rate floor.

Ford said the state’s child care subsidy program serves 51,000 children statewide, which is less than 15% of eligible children. And the subsidies reimburse less than half the cost of a classroom slot. That’s because the rate is based on what families can afford to pay, not what the service actually costs to provide.

Of particular concern to Ford is what she calls the “rural disadvantage” when it comes to the subsidy reimbursement rate.

Because the rate is based on what local residents can afford, it is typically lower in rural areas with a lower cost of living and income base.

“What we have learned over the years is that it doesn’t actually cost a whole lot less to run child care in our rural communities; their costs just look different,” Ford said.

When the Southwestern Child Development Commission announced plans to close seven programs in the western part of the state last year, Ford asked them about subsidies.

“I said, ‘What would have happened if that subsidy rate floor had been in place?’ and they said, ‘That would have made our bottom line work,’” Ford told the oversight committee.

Ford also said the continued underfunding of NC Pre-K needs to be addressed.

NC Pre-K is a statewide public preschool program designed to support low-income 4-year-olds at risk of negative education outcomes. It’s serving less than half of eligible students and costs $11,330 per student for one academic year.

Of the eligible students enrolled, more than half are in classrooms operated by public school systems, which receive $10,791 per student. But almost half of classrooms are operated by private programs, which receive only $5,450 per student — 48% of the total cost.

“I love our school districts, and we partner with them all the time, but they don’t have space or room or even necessarily the function of doing [NC Pre-K] for all across the state,” Ford said. “We need our private providers in that [they] are the ones set up for zero-to-five care. That’s their bread and butter.”

This article first appeared on EducationNC and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)