NC’s Top Court Compels State to Turn Over $800 Million in School Funding Case

While the court planted a ‘flag post’ in the ongoing saga, Republicans call the ruling “unconstitutional” and promise to fight it

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A recent decision by North Carolina’s top court compels the state to turn over close to $800 million to the education system, a move that could influence other states facing challenges over the adequacy of public school funding

In a 4-3 ruling handed down Nov. 4, the North Carolina Supreme Court took the matter out of the legislature’s hands after almost 30 years of litigation and ordered officials to transfer the funds directly from the state treasury to agencies overseeing education and teacher preparation.

“Far too many North Carolina schoolchildren, especially those historically marginalized, are not afforded their constitutional right to the opportunity to a sound basic education,” Associate Justice Robin Hudson wrote in the majority opinion in Hoke County Board of Education v. North Carolina. The state, she said, “has proven — for an entire generation — either unable or unwilling to fulfill its constitutional duty.”

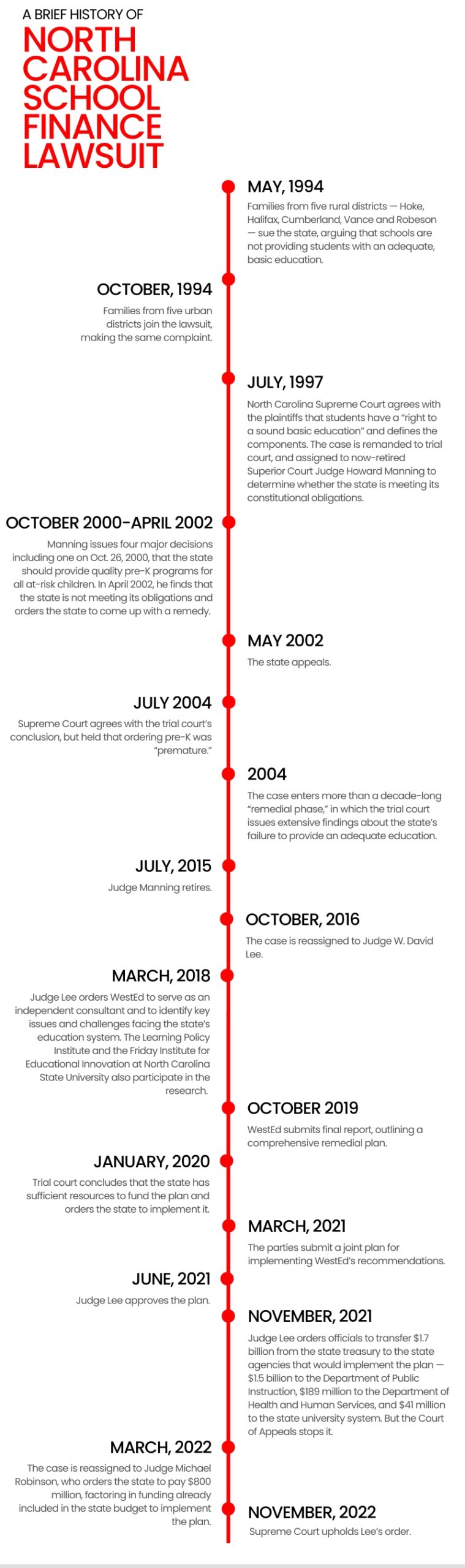

Part of a wave of lawsuits from the 1990s that challenged inequitable school funding systems, the case — first known as Leandro v. North Carolina — shed light on the lack of educational opportunities in five rural counties, where underqualified teachers, scarce supplies and outdated textbooks were the norm. The plaintiff districts argued that the state was responsible for making up the funding gap between poor and wealthy districts.

The case languished in the courts even as the state amassed a budget surplus following the Great Recession. Derek Black, a law professor at the University of South Carolina, said the ruling sends a signal to other states that legislators can’t ignore the law.

“The games that legislatures play are … wars on the right to education, wars on the constitution,” said Black, who attended “marathon” hearings on the case when he was in law school at the University of North Carolina. “When the judiciary speaks, there is not some other option.”

Republicans, who dominate the legislature, are already pushing back, and with the GOP gaining a 5-2 majority on the Supreme Court in last week’s election, some are floating the possibility of a reversal.

“Prediction: Not a dime of taxpayer money is ultimately spent on this unprecedented and unconstitutional order before it is blocked and reversed by a newly seated N.C. Supreme Court next year,” tweeted Brent Woodcox, a Republican senior policy counsel for the North Carolina legislature.

In his dissent in the case, Associate Justice Phil Berger Jr. set the stage for a backlash. He wrote that the ruling “strips” the legislature of its authority over education policy and funding and amounts to “pernicious extension of judicial power.”

But in the majority opinion, Hudson sought to limit the ruling’s scope, writing that it applies “in exactly one circumstance” — this case — and wouldn’t have been necessary if “recalcitrant state actors” had addressed the funding inequities.

Lawrence Picus, a school finance expert at the University of Southern California, said the closest example to this ruling he has seen is a 2015 order from the Washington Supreme Court that held the state legislature in contempt and issued a $100,000-a-day fine until lawmakers agreed on a way to adequately fund schools as mandated by the court’s opinion in McCleary v. State of Washington.

That day didn’t come until June, 2018, when the court ruled that the state had increased the education budget enough to be in compliance. Penalties, which by that time had reached over $100 million, also went to schools.

“Courts are generally extremely reluctant to order the legislature to do something,” Picus said. “In North Carolina, they’re doing it for them.”

Funding the ‘remedial’ plan

Originally named for Hoke County Schools student Robb Leandro and his mother, the North Carolina case began in 1994 when families from five rural districts sued the state and its board of education. The lack of well-qualified teachers, they argued, left students less likely than those in wealthier counties to be proficient in core subjects and to enter college without needing remediation.

Despite the trial court siding with the plaintiffs year after year, lawmakers never complied with the orders and, following the Great Recession, cut education by a further 13.9% in per-student funding, according to one analysis.

But then the financial picture improved — a lot — and this year, the state has a $6 billion surplus.

A year ago, the trial court ordered the state to spend $1.7 billion to help fund an eight-year “remedial” plan developed byWestEd, a consulting firm. The funds would cover teacher and principal training, revisions to the school funding formula and expansion of the state’s pre-K system.

The state later passed a budget partially funding the plan, and the trial court revised the figure to $785 million. The Supreme Court’s ruling upholds that decision.

Republican House Speaker Tim Moore told local reporters the legislature plans to “revisit” the ruling, while attorneys with Parker Poe, a law firm that represents the plaintiffs, said that’s not an option.

‘Whether they agree with it or not’

Like Black, Ann McColl has seen her law career intertwined with the Leandro saga. Co-founder of The Innovation Project, a school leadership network, she represented and wrote briefs in the case on behalf of educator and school board associations.

“It’s always the case that people react to a court opinion, and see how they can maneuver around it,” she said. But North Carolina lawmakers, she added, are showing a “certain vigor” in their objections.

There’s a potential for the ruling to influence a school finance lawsuit in Pennsylvania. Earlier this year, an appellate court heard four months of testimony in that case, with attorneys for legislative leaders arguing that students don’t need to go to college if they’re on “the McDonald’s track.” The case is expected to make its way to the state supreme court.

Until now, Black added, the so-called 1989 “Rose decision” in Kentucky stood as the most forceful ruling in school finance. The state supreme court ruled that Kentucky’s entire education system was unconstitutional and defined the elements of an adequate education.

The North Carolina decision goes further by ruling that schools needn’t wait for lawmakers to act.

“The court just put down a flag post,” Black said, “and every single court that grapples with this issue in the future will discuss this flag post, whether they agree with it or not.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)