Most Schools Have Long Had Pandemic Plans. But a Watchdog Warned Years Ago That Half of All Districts Had No Real Strategy for How to Operate If Classrooms Remained Closed

The coronavirus pandemic isn’t the first time in recent memory an outbreak forced schools to close. It was just a decade ago that the swine flu killed thousands of Americans and shuttered hundreds of K-12 campuses in 24 states.

Though far less disruptive than the latest pandemic, the 2009 outbreak should have been a “wake-up call” that widespread school closures could sweep the nation, said Thomas Chandler, a research scientist at Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness.

Most leaders missed the alarm.

“There has been a growing body of research from epidemiologists saying that it’s not a question of if but when this type of disaster could occur,” Chandler told The 74. But leaders across all levels of government failed to envision “a pandemic that would go on this long.”

At the time of the swine flu and even years earlier, schools maintained emergency response plans to meet a host of tragedies, from hurricanes to school shootings — including viral outbreaks. But experts said many of those plans didn’t take pandemics seriously, and those that did failed to adequately envision our current reality: months of campus closures and widespread virtual instruction.

Now, as a new school year is about to begin with many campuses still shuttered, the coronavirus has generated renewed scrutiny of schools’ emergency preparedness and prompted calls for major changes in the post-pandemic future.

Among those who sounded the alarm was Terri Rebmann, an epidemiology professor at Saint Louis University and director of the Institute for Biosecurity. Through lectures and articles, she’s warned educators for years about the possibility that a pandemic would force widespread remote teaching — and urged them to prepare. But she said the concept never seemed to stick.

In a 2012 survey of nearly 2,000 school nurses across 26 states, fewer than half said their district updated emergency plans after the 2009 swine flu outbreak despite major gaps in preparation. While nearly half of respondents said their schools had emergency plans that addressed pandemics, just 4 percent said they conducted drills for infectious disease scenarios over a two-year period. Meanwhile, less than a third of schools stockpiled personal protective equipment like surgical masks and gloves, and less than a quarter trained all staff members on how to apply their disaster protocols.

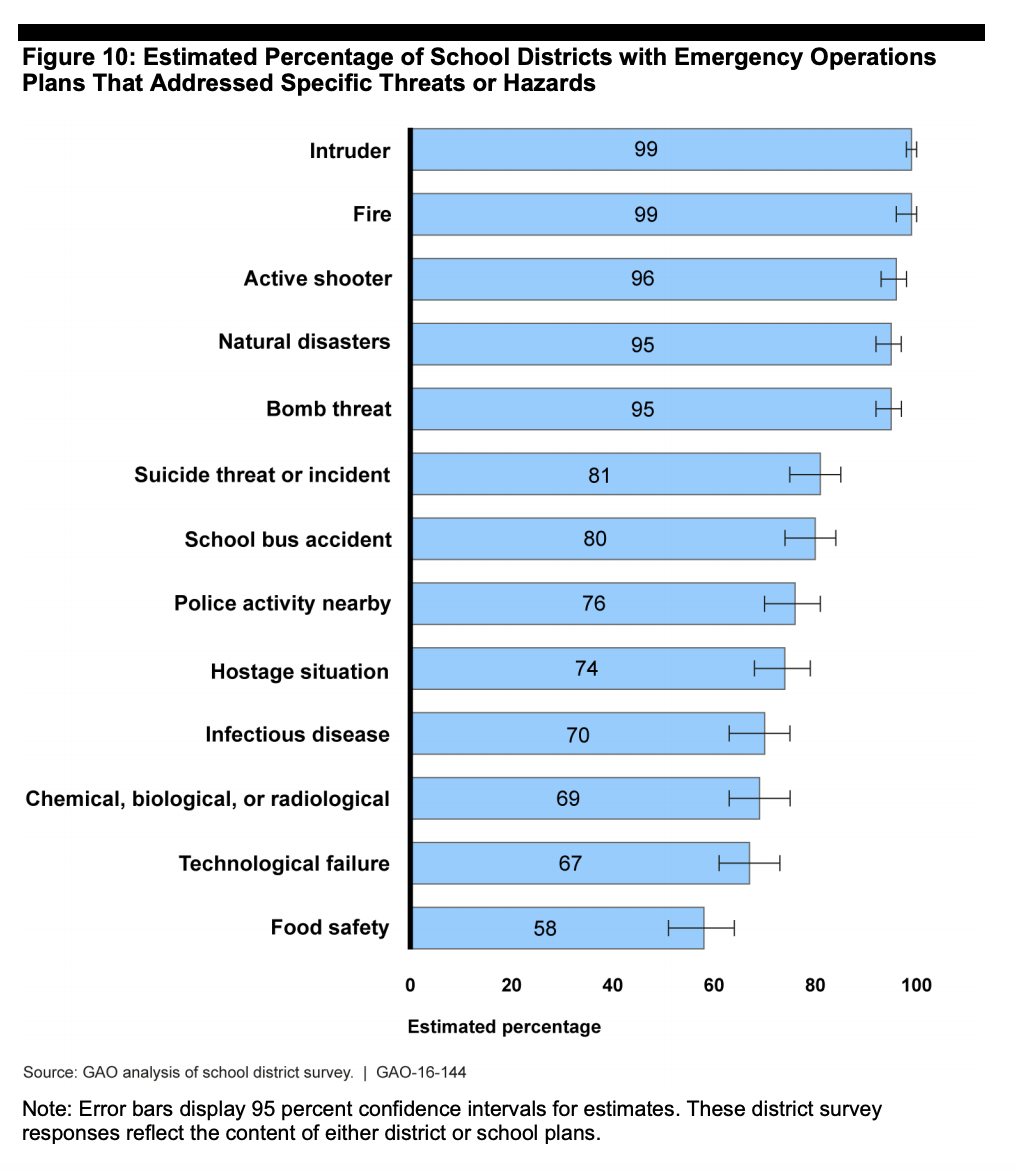

Though no national laws require schools to have emergency plans, the federal Government Accountability Office has observed holes in district preparation for more than a decade. In one study, from 2016, the federal watchdog found that 70 percent of districts maintained protocols on infectious disease outbreaks and only half outlined how to keep district operations afloat — or how to resume schooling after tragedy subsides. For example, one district’s plan didn’t “comprehensively address” how to maintain continuous operations but noted the possibility of online lessons should campuses close for an extended period.

“Here we are five years later, and it turns out that’s certainly one of the most important things that districts are wrestling with,” said Jackie Nowicki, director of GAO’s education, workforce and income security team. “Folks can make their own judgment as to whether they believe that schools and districts were really prepared,” she said, but figuring out how to offer remote learning over the long haul — and how to return children to classrooms — has “really turned out to be where the rubber hits the road.”

Most district plans outlined procedures on how to respond during a range of emergencies — such as when and how to evacuate during a fire — but several factors hindered their ability to maintain them. More than half of district leaders said they struggled to balance the demands of emergency planning with other key priorities like classroom instruction.

Despite a federal investment of millions of dollars in emergency plans, the GAO found that the government took a “piecemeal approach” and that insufficient coordination between agencies may have hindered their ability to help schools prepare for a disaster. Since the GAO issued its report, government agencies have made strides, Nowicki said. After the 2018 mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida, for example, federal agencies partnered to create a website that compiles resources on school safety, including recommendations for crafting emergency plans.

But are districts using these resources? In the 2016 report, the GAO found that despite the availability of federal help, more than two-thirds of districts hadn’t relied on it.

During school visits, district leaders said they “really relied more on their state for guidance rather than on the federal government directly,” she said. “Perhaps some federal standards and guidance were not tailored to their needs.”

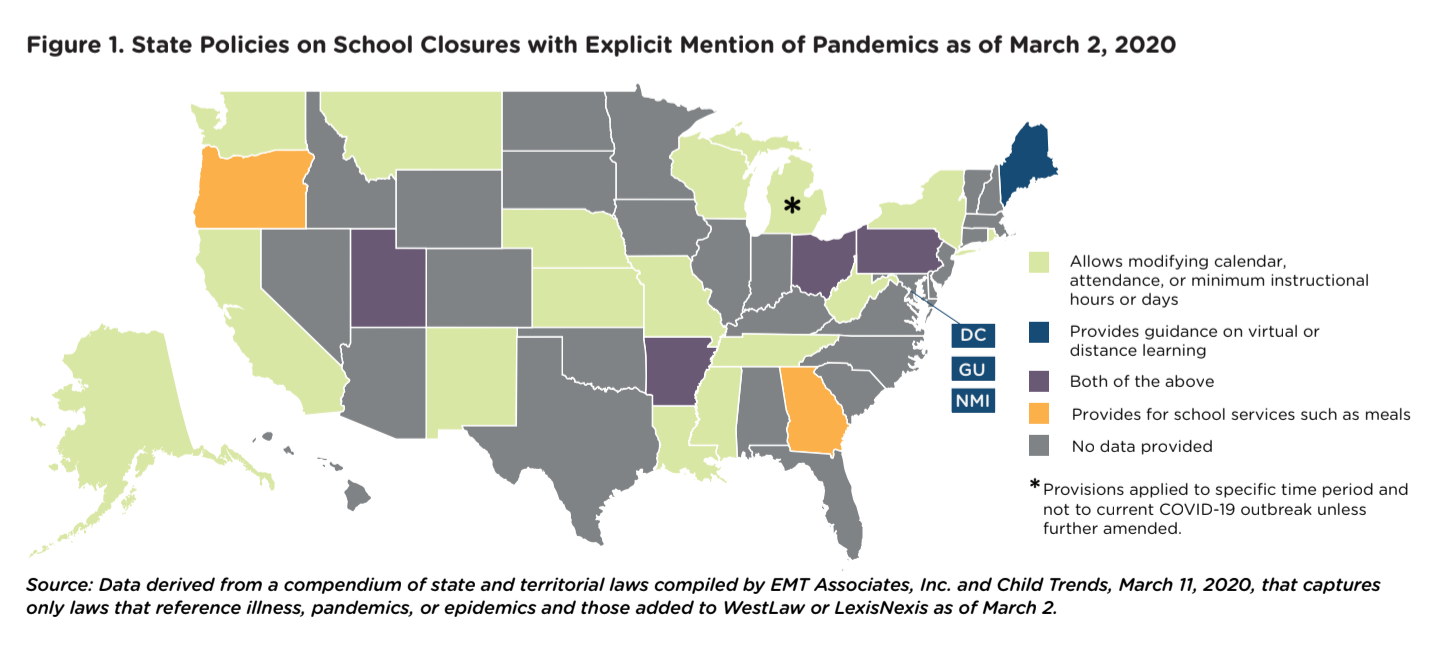

But a study released in March calls states to task as well. Prior to the pandemic, all states except one — New Hampshire — had rules outlining how schools should respond to a disease outbreak, but the content and rigor of those policies varied widely, according to the recent analysis by the nonprofit Child Trends. Many states don’t require school leaders to prepare for issues such as emergency staffing, remote instruction or providing students crucial services like meals.

In Ohio, for example, school districts are required to have school safety plans, but protocols on pandemics are only considered a “best practice.” Meanwhile, in Georgia, state rules instruct districts to craft policies that consider the effects an infectious disease could have on school operations, and district employees are required to receive training on containing an outbreak. In Oregon, state law establishes a school lunch program in the event a pandemic-related illness forces schools to close for at least five days.

Although the bulk of schools’ pandemic plans focus on strategies to slow the spread of an outbreak, only five states considered distance learning “on a wide scale,” said Deborah Temkin, Child Trends’ vice president for youth development and education research. Many states considered how to provide services to critically ill students, but none weighed the possibility that on a moment’s notice, all students would be sent home from school for months.

School district plans suggest that many local leaders failed to envision extended campus closures. One Connecticut district’s plan, published in February as the pandemic began to sweep across the U.S., notes that protocols to maintain school operations during campus closures have “not been determined at this time.” A Colorado district’s plan, also from February, notes that if students were forced to miss “several days of instruction,” the district would launch a “return to learning” program to get students back on track and that some assignments could be eliminated.

Inadequate preparation has come with consequences for both teachers and students, Temkin said.

“Hindsight is always 20/20,” she said. “But what we’ve seen across the country is that there’s been bungled rollouts of virtual learning and, frankly, that teachers themselves just haven’t been prepared.”

Part of the problem comes down to money. Although districts’ emergency plans were “sort of” helpful when the pandemic became a reality, an inconsistent stream of funding to develop and maintain them hindered their effectiveness, said Jeff Schlegelmilch, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia. Though canceling in-person schooling and other public gatherings is “on page one of the playbook” for responding to pandemics, he said, districts’ failure to plan for continuous operations before campuses shuttered “reflects the transient nature of our preparedness funding.”

“It’s very expensive and it’s very time-consuming to do the type of preparedness to make this as smooth as possible, but I think we’re also seeing the cost of underinvesting,” he said. “The kids who are missing out on educational opportunities are going to be the ones who carry it with them throughout their lives.”

The next wave

Though educators’ response to the pandemic varied widely, districts that had endured previous disasters tended to fare better when confronted with COVID-19, experts said. Among them is the school district in Miami, which has long maintained an emergency response plan that factors in the possibility of a pandemic and has been lauded for its quick response to the current crisis. The district was also prepared technologically: It already had some 200,000 laptops to distribute among students.

“We were able to obliterate the digital deserts almost overnight by simply deploying the assets that we had at school into the hands of students,” Superintendent Alberto Carvalho said in an interview. The district bought the devices to combat the digital divide between affluent and low-income students, he said, but it left the district in a better position than others that scrambled to buy and distribute devices after campuses had already closed.

Maintaining operations for a long period became a key sticking point as the district braced for schools to shutter. Occupying a coastal city perpetually beset by hurricanes, Miami schools have had to confront interrupted instruction in the past, “but this was at a magnitude we really have not experienced before — and a prolonged period of time never before seen,” Carvalho said.

To prepare, the district created an “instructional continuity plan.” Before the pandemic, the district had maintained distance learning procedures, but they weren’t prescriptive, Carvalho said. The new plan outlined attendance policies, remote instruction strategies and grade-level course materials.

“Within two weeks, we had a second version with accountability for teachers and students and parents, and the state of Florida by and large adopted our plan,” he said. By preparing in advance, the district made its transition to remote instruction relatively seamless, he said. “On the basis of access, we were able to guarantee equity from day one.”

Miami was largely an outlier. Nationally, districts botched the transition to online learning, Temkin said. But she said it’s crucial that districts learn from their missteps.

“Now, it’s not the question of ‘What if they would have done this’; it’s ‘What they should do now,’” she said. Going forward, she said, district planning should include educator professional development on online learning, technology access for low-income children and a greater emphasis on addressing students’ physical and emotional health.

In the near term, school leaders will need to be flexible as the pandemic unfolds. But as they prepare for the future, they need to think beyond the immediate academic effects, such as “Covid slide,” Schlegelmilch said.

“There’s an immediate need to come up with viable educational strategies that are going to be applicable throughout this pandemic, which is nowhere near over,” he said. “And then, this isn’t the last pandemic that we’re going to see — maybe not even in our lifetimes.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)