Most Pregnant and Parenting Students Don’t Graduate. Here’s How One Rhode Island High School Is Helping Its Teens Beat the Odds

Providence, Rhode Island

She’s only 17, but Gionna Martin works harder than many people twice her age.

Martin is a full-time high school senior and a teen mom. The sole provider for herself and her 11-month-old daughter, she works nights and weekends at a craft store in her hometown of Providence. And, as she’s graduating in June, she’s navigating the complicated and stressful college application process.

During conversations, Martin yawns frequently (which she apologizes for — she often works six-hour evening shifts). It’s exhausting, managing the economic and academic challenges confronting teen mothers: About half live in poverty, and the majority of those who have a baby before age 18 never earn a high school diploma.

“Nobody told me, ‘Hey, you’re going to be up at 2, 4, 6, 8:00 in the morning,” Martin said. “ ‘Oh, you’re never going to get to sleep in again a day in your life, and oh, by the way, the rest of your life you’ll be in debt because you’re going to have to buy diapers every three weeks.’ ”

But Martin can’t help but smile when she talks about her daughter, Jayvionna, and she’s determined to beat the odds for both of them. In fact, she wants to be a lawyer, and she has found a rare high school that supports and nurtures her ambitions for herself and her child.

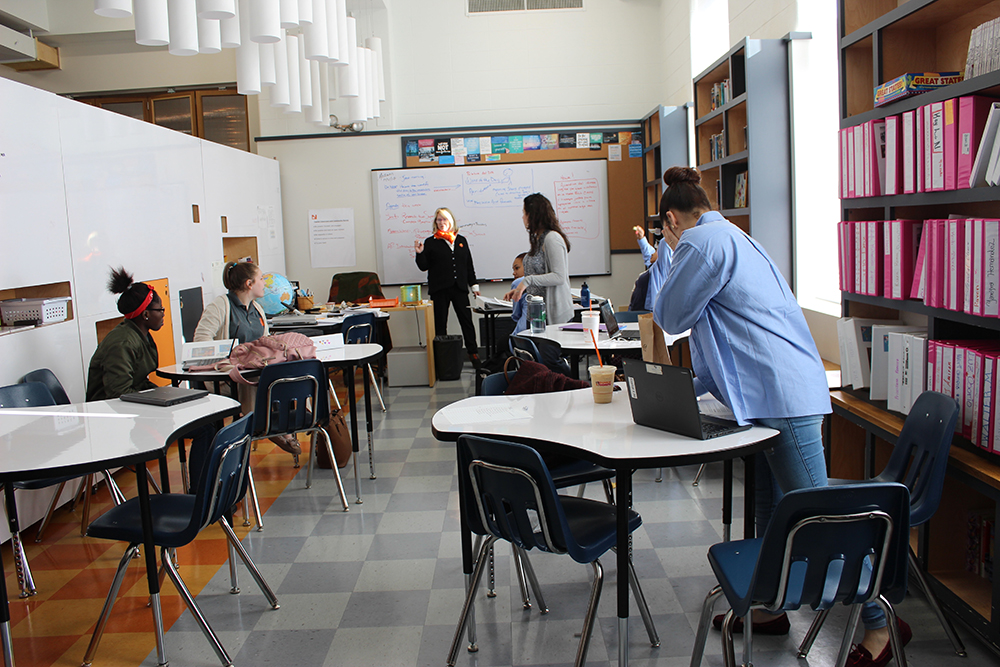

Nowell Leadership Academy charter school, with campuses in Providence and nearby Central Falls, is one of the few high schools in the country dedicated to graduating pregnant and parenting students fully prepared for college, careers, and family life. The school’s 160 students — mostly transfer students and overwhelmingly female, with some male students who are also struggling to make up credits — have flexible schedules, personalized learning tools so they can work at their own pace, help with transportation, and support for raising their families, from parenting classes to home visits after they’ve given birth.

It’s a hard model to implement successfully, and other pregnancy schools have closed for failing to provide students with a quality education. New York City’s 50-year-old P-schools, for example, were shuttered in 2007 for low attendance, inadequate facilities, and poor academics — rather than learning geometry, girls in math class were found to be sewing quilts.

Nowell itself is in the midst of a reinvention, as it seeks to improve its attendance rate while maintaining flexibility for its parenting students, many of whom are overage and undercredited. The stakes are high as Nowell educators try to crack that code — for 40 percent of the students, Nowell is their third high school.

“Charter schools have become a second chance for kids; our school has become a last chance for kids,” said Conor Sheehan, dean of students at Nowell.

The students who show up at Nowell also know the stakes are high. Learning to be a good parent is a huge concern for them. They want to make sure their kids are in a good day care. They think about their babies during science class and check their email often in case the day care has sent them a picture or update. They read their children books before bed to increase their vocabulary. They sing to them. They learn CPR so they know what to do if their kid is choking. They think about getting a good job so their daughter or son can go to a high-quality school.

They’re still students — some are legally still children — but they already want what the U.S. education system, in theory, is supposed to provide: an opportunity for a good life.

Discrimination, despite federal law

In theory, all high schools are supposed to make this opportunity a reality for their pregnant and parenting students by providing appropriate accommodations. After all, strict daily attendance and homework deadlines are difficult for students like Martin, who is trying to raise her daughter, earn a diploma, and pay the rent. But instead, many students end up being pushed out.

This isn’t supposed to happen: Federal law forbids discrimination against pregnant and parenting students under Title IX. They are supposed to be able to make up missed work, to have absences excused, to receive home services similar to those given to students on medical leave. Yet pushout is “extremely prevalent,” said Neena Chaudhry, director of education and senior counsel at the National Women’s Law Center.

Nowell senior Kelsey Barney, 17, missed two months of class at her old high school while caring for her newborn daughter, Alyssa, who had a fever. When she came back, Barney said, she was told she couldn’t graduate on time.

“My guidance counselor looked at me and said, ‘You should either choose school or your child,’ ” Barney said. “I chose my child.”

Chaudhry said stories like this aren’t uncommon.

“We hear from women in high school, college, and graduate school about their schools failing to accommodate them,” she said. “They really do end up putting women behind in a way that they don’t receive the support they need or are outright discriminated against.”

This discrimination is reflected in the data: Only 38 percent of teens who have a baby before age 18 earn a high school diploma. Their children are also less likely to graduate, and they perform worse than their peers on standardized tests. Half of teen moms live in poverty, and that likelihood increases as their child ages, usually because the teens leave their parents’ home. And many of these women are on their own: 58 percent of teen moms don’t receive financial support from the father of their child.

Minority teens are the hardest hit. While the overall U.S. teen birth rate has dropped 67 percent since its peak in 1991, it is still highest among young women of color: The total rate in 2016 was 20.3 live births per 1,000 girls ages 15 to 19, but it was 35 for Hispanic women, 32 for black women, 26 for American Indian/Alaskan Natives, 16 for whites, and 7 for Asians.

Nowell’s student population reflects many of these demographics: More than 80 percent qualify for free or reduced-price school lunch. Fifty-five percent are Latino, 19 percent are white, and 15 percent are black, and 20 percent have Individualized Education Programs, requiring special education services.

A school model in progress

As Nowell’s students struggle to complete their educations, the school has struggled to figure out how best to serve them. Nowell opened in 2013, but for the first three years, average daily attendance was 25 percent.

Concerned that the school wasn’t adequately serving its students, the board of directors brought in new leadership last year to build in more structure and supports. Nowell purchased slots at nearby child care centers for students to use while waiting for state funding to pay for day care. It brought in Summit’s personalized learning platform, which lets students go through the curriculum at their own speed; hired reading and math intervention specialists; instituted partial uniforms (while accommodating pregnant students’ changing bodies), and arranged for dual enrollment for dozens of its students at several local colleges. The school helps subsidize transportation between home and school, and to and from college. Educators make home visits to students who stop coming to school, to figure out how to get them back.

Last year, attendance averaged about 63 percent — still low, the leaders admit, but a significant improvement. On its most recent school report card, Nowell averaged a 45 percent six-year graduation rate, which includes time spent at the students’ previous high schools. Many of the students arrive at Nowell below grade level, over the age of 18, and lacking in credits.

“We’re really working hard to figure out how do you create a high-performing, high-expectations charter school that’s really zeroed in on this population of 18-, 19-, 20-year-olds who are still trying to finish high school and then move on to post-secondary success,” said Toby Shepherd, Nowell’s executive director. “If and when we perfect our model, it’s going to be of good value to our state.”

‘Somebody else that’s worried about me’

It’s Wednesday afternoon. Nowell teacher-nurse Judith Russell parks her car in a residential neighborhood of East Providence and walks across the street, a big bag of diapers in one hand. A young woman answers the door and leads Russell into a dark room, where a week-old infant sleeps in a rocking seat, wrapped in a pink and blue blanket. “Happy Birthday” balloons spin slowly in the corner.

The 16-year-old student is shy — she asked not to be identified — but Russell goes through her questions in a slow, subdued voice: How is breastfeeding going? Did you find the soft spot on the little girl’s head? Did it scare you? Do you know who’s going to watch the baby when you come back to school? Is the state going to help? Did the hospital talk to you about birth control? How are your emotions?

Russell’s job is to make sure Nowell’s students aren’t left behind after having a baby. If the new mothers agree, she visits them at home right after they get out of the hospital, serving as both a visiting nurse and a teacher. She provides medical advice and sets up students with a laptop and learning plan, so they can work from home for a few months before returning to school.

“How am I going to access Wi-Fi, because we don’t have it here?” the student asks Russell.

“I’ll bring you a Wi-Fi box,” Russell promises.

Back at school, students said they find her consultations helpful. During her home visits, Martin remembered, Russell reminded her she shouldn’t walk around so much after her C-section. Martin also turned to Russell for CPR training, after worrying about how to help her daughter if she started choking.

“Miss Judith, when it comes to my baby, it’s really easy to talk to her because you could tell she’s not judging you, she’s genuinely concerned about you and your child,” Martin said. “It’s nice to have somebody else that’s worried about me or my baby all the time besides me.”

Russell also teaches health classes covering family life, sexuality, and contraception. She’s become the go-to coach and counselor for Nowell’s students as they navigate their first pregnancy, become a parent, and try to figure out finances and housing.

Like family

Beyond academics and life skills training, one of Nowell’s big draws is that students feel welcome there in a way that they weren’t at their former schools.

“One of the reasons they like Nowell, even if we can’t do everything, is they feel much more accepted that they are pregnant,” Russell said. “It really does surprise me that in this day and age, in a large urban public school, they still get all kinds of attitude and ridicule for being pregnant. … Our school, the kids have been through a lot, and they’re really accepting of differences.”

Barney said she was called names at her other school and physically pushed in the hallway after her classmates found out she was pregnant. But at Nowell, the teachers check in with her during the day, asking about her daughter — the environment, she said, is like “family.”

The students share advice and ask each other questions, Martin said. “A lot of the girls here have babies, and the girls who don’t, they’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m so happy for you,’ ” she said. “They’re not judgy, they’re like, ‘We understand what you’re going through because we’re going through it too, we’re young moms too.’ ”

The girls at Nowell said they feel bad for the young women at other schools because of the judgment, harassment, and strict rules they previously encountered.

“I feel like other schools, they try to have a blind eye towards it, teen pregnancy,” Martin said. “I want other girls in my situation who can’t come here to feel OK in their school. If they want to finish school, if you see somebody pregnant in school, be happy for them. They’re still in school and they’re pregnant. … It’s really hard.”

Making it all add up

“What do you do when your kid goes crazy?” a student asks math teacher Areema Sweeney. Like many of her students, Sweeney has young children, ages 1 and 2. It isn’t a math question, but Sweeney understands how pressing it is: Babies can easily distract young moms from doing their homework.

Peanuts are a good trick, Sweeney says, remembering how calmly her son sat as he tried to open the shells. Then Sweeney pauses for a moment with the student and brainstorms other engaging play items: coloring books, crayons, and puzzles.

This is Sweeney’s first year at Nowell. She used to work at a private school and a charter school, and she recalled her frustration with the strict traditional school schedules that didn’t support many pregnant and parenting students.

“I feel like a lot of students, or a lot of young girls, if they do get pregnant in high school, that’s the end of the road for them, you know: ‘Oh man, I had a baby young, now I can only do this or have these dreams,’ ” Sweeney said. “It’s refreshing to see a model where they’re not a lost cause, there’s still hope for you and we’re going to get you where you want to be.”

Transitioning to a school where only half to three-quarters of the class is present at any given time was difficult, Sweeney said. She had to develop new teaching techniques so she wasn’t constantly repeating lessons for the students who did show up: She leaves lessons up on the board rather than erasing them. She has students take notes in an “interactive notebook,” where strategically placed index cards are taped over information to serve as a study tool. Students who are ahead of the class take quizzes on their personalized learning platform to show mastery of material their peers are still learning. She sometimes spends time after school answering math questions by text message.

Most important, she has to maintain her high expectations.

“My classes will never be easier, I tell them that all the time. I’m a tough teacher and I expect you to learn the material and prove that you know the material,” Sweeney said. “But I will give you the time and support you need. That time difference, that hard-set deadline when everything has to be completed, is a real obstacle for pregnant and parenting teens.”

How to be a parent

In most U.S. schools, students can safely travel through the education system, even finish graduate school, and never learn how to be a parent.

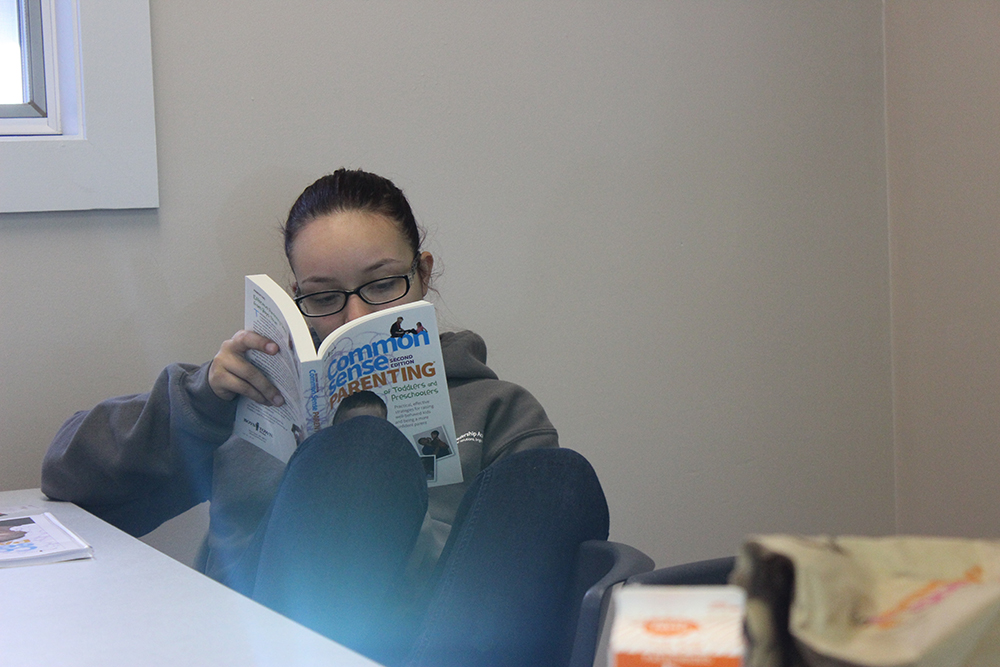

That’s not the case at Nowell, where preparation for family life is required for graduation. One class period a week, a nonprofit called Boys Town comes to the school to teach skills like how to communicate with children, how to get them to listen, how to discipline them, and how to effectively praise them.

It’s a pass/fail class, with homework that requires students to practice their skills on their children. Some students find the class helpful, while others say it’s just common sense. But judging by the laughter filling the room during a lesson, they all seem to find it entertaining.

On the classroom wall, instructor Jose Cabrera projects a video of two young girls splashing each other with water from a bathroom sink. He calls on students in turn: How would they respond if this were their child?

The students urge Cabrera to call on Ashley, 16, the only one in the class with two girls: a 1-year-old and a 4-month-old.

Cabrera complies. “So, Ashley, you’re walking in and your two daughters are throwing water on each other.”

“I think I would laugh,” she says.

Cabrera laughs too, but waves his hands: “This is not good! Parents tell me, ‘I’d join them.’ No, this is negative, we’re not OK with this. We’re going to tell them what we’re doing and why we want them to stop, OK? And then give them a consequence.”

“I would just tell them that they shouldn’t play with the water and have them dry it up,” Ashley says.

“That’s perfect,” Cabrera says. “And good contingent on behavior.”

‘Motivation because of him’

It would be easy to blame these students’ tumultuous lives on their babies. But the students say it is because of their children that they’re motivated to earn a high school diploma and go to college.

Krisia Barraza, 18, lives in a group home with her son, Noah, and transferred to Nowell in part because of the day care right next door to the school. Being able to check on Noah during the day keeps her calm and helps her focus on her classwork. When she brings out her laptop to do her homework, Noah gets excited and tries to play with it. It’s distracting — but he is what drives her to finish school and find a job.

“It’s a little bit hard, but at the same time it’s good ’cause I have that motivation because of him,” said Barraza. “If it wasn’t for him, I really wouldn’t do it for myself. I haven’t been on top of my school stuff, so now I actually have a reason to do it, and it feels good.”

For Barney, her daughter is “the reason” she goes to school, takes college classes, deals with all the stress and drama. “She deserves the best,” Barney said of Alyssa. “She deserves to have, not everything she wants, but most.”

Like many of the students who are parenting without the father of their child, Barney is determined that her daughter will be as resilient as she has become.

“I want my daughter to know that she doesn’t need a man in her life to provide for her,” Barney said. “I know I don’t. I know my mom doesn’t, ’cause I was raised, my mom was a single mom, so I want her to know if she sets her mind to it, she can do anything.”

The family you’ve got

Sometimes, the most challenging part of the day is the thing that makes it worthwhile.

It’s 2:45 p.m. Tuesday afternoon on Halloween. Students stream out of the Nowell building, several crossing the courtyard to the day care. Maciel Varona, 19, walks back into the school, balancing her 2-year-old daughter, Aleah, on one hip. Smiling students and staff flock around Aleah, trying to make eye contact with the toddler, who stares around the room silently with big brown eyes.

Maciel stands Aleah on a desk and pulls her small arms through a fluffy, neon pink pig costume, with a snout, ears, and eyes decorating the hood. Aleah blinks, slightly confused by the strange outfit garnering so many squeals from onlookers. Maciel hugs her and lifts her up, back onto her hip.

Aleah is approaching the “terrible twos” stage, Varona said — she refuses to get dressed in the morning and messes up her hair after Varona brushes it. It’s fun but not easy being a parent, Varona said, balancing college classes, high school courses, and career goals. But like her classmates, Varona feels a need, rather than a mere want, to give her daughter a good life.

“I can’t be like, ‘Oh yeah, I want to do this and have a kid.’ It’s like, ‘I have to do this in order to get my kid where I know she needs to be.’ ”

It’s also why Martin will continue working twice as hard as a woman twice her age. There’s a little girl at home who throws her shoes and loses her socks, but every night Martin comes home from work and reads her daughter Dr. Seuss to increase her vocabulary. When Martin sings to her, the baby smiles.

“It’s what I work for,” Martin said. “She’s the only family I’ve got.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)