Most Educators Assess Their Students’ Social-Emotional Learning, but Few See the Whole Picture. Here’s What They’re Missing

Many teachers in Woodridge School District 68, located 30 miles west of Chicago, used to think their low-income students had little grit and their gifted students had lots.

At least, this was a pattern that emerged when teachers filled out surveys about their students’ skills. But when their pupils took assessments to measure their social-emotional abilities, the educators found the exact opposite to be true. Their students from disadvantaged backgrounds were more likely to persevere, while those who were the best in the class found it much harder to persist when faced with challenges.

The results were eye-opening and were possible only because the school district used several different assessments to measure how social-emotional learning is being taught in their schools. It sounds like a lot of work, but right now, it’s a best practice for schools interested in seeing whether their efforts to teach students skills like self-regulation, collaboration and social awareness are working.

Most educators say they’re assessing social-emotional learning in their classrooms, according to a recent analysis from the RAND Corporation of national teacher and principal survey data. But the report found that the assessments they use don’t always capture the whole picture.

A majority of teachers and principals are measuring school climate — whether students feel safe to learn, whether they have good relationships with adults — but fewer are testing how well students can demonstrate actual social-emotional skills like self-management, compassion and taking someone else’s perspective.

“Measurement of student social-emotional competencies is kind of a newer field, and there are fewer resources out there,” said Laura Hamilton, director of the RAND Center for Social and Emotional Learning Research and a co-author of the report. “It’s not something that most teachers and principals have experience doing, even though there’s a lot of interest in doing it.”

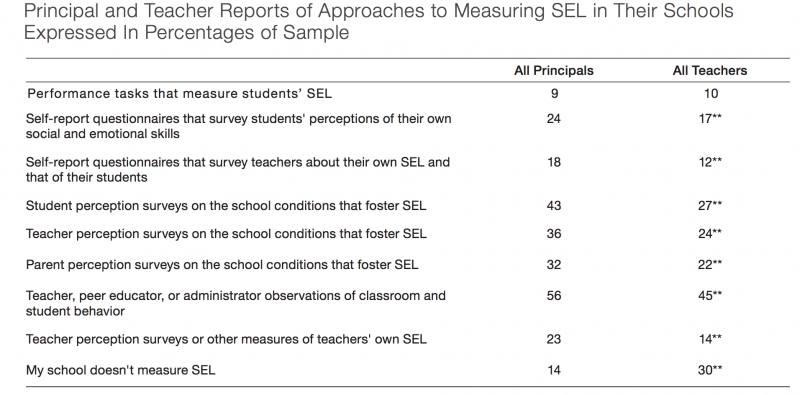

The most common way educators measure social-emotional learning is through observing the classroom environment and their students’ behavior, with nearly half of all respondents saying they use this method. The next three most common measurements are student, teacher and parent surveys of how the school environment promotes social-emotional learning.

The least popular assessment used in schools was performance tasks that measure a students’ social-emotional capabilities, with only about 1 in 10 educators saying they use this method.

Thirty percent of teachers and 14 percent of principals said their schools don’t measure social-emotional learning at all. The RAND report said this seemingly strange difference in response might be because principals are more aware than teachers of the different ways SEL is being assessed in a school.

The focus on school climate rather than student social-emotional capabilities is not a surprising finding for researchers, who are also grappling with how to assess these so-called soft skills. Surveys to measure a school’s climate or culture have been around for awhile, while testing for social-emotional competencies is newer. That’s why both RAND and the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) have resources to help educators find assessments for measuring their students’ social-emotional skills.

In the case of the Woodridge district, these types of analyses can change instruction. After educators discovered their own biases in evaluating students’ social-emotional abilities, they were able to set higher expectations for their students who demonstrated grit and perseverance. They were also able to encourage their students who had fixed mindsets to persevere with difficult tasks.

Just like a bird needs two wings to fly, so too do students need support for both their social-emotional learning and their academics, said Greg Wolcott, assistant superintendent for teaching and learning at Woodridge.

“In schools, if we only develop the academic wing and not the social-emotional wing, our kids go in a circle,” Wolcott said. “If we feel it’s important to assess students in multiple areas of academics, we need to assess multiple areas of social-emotional learning.”

All schools in the district use two different social-emotional assessments at the beginning of the year and again at the end of the year — a teacher evaluation of their students’ abilities and students’ self-report surveys. The elementary students also take a third assessment that measures their social-emotional strengths and needs. This is a performance task, so students might watch the changing faces of characters on a screen and be prompted to describe how they’re feeling.

Clark McKown is a social-emotional learning researcher and the founder and president of xSEL Labs, which runs these performance assessments that Wolcott’s elementary students use. McKown says it’s critical to use different types of social-emotional assessments to analyze different skills.

For example, to understand a student’s growth mindset — whether kids believe that they can learn and grow with effort — you have to ask the students directly, so a student survey would be a better method than a teacher evaluation or a performance test, he said. But if you’re measuring student behavior, a teacher’s report would be the best method. And to see whether students can act on their knowledge — such as being able to take another person’s perspective — a performance test would be better.

“My hope is that there’s increased recognition that measuring both climate and student competence provides a richer picture than just measuring the one or the other,” McKown said.

Not everyone is a fan of measuring students’ abilities. Both Hamilton and McKown said there are concerns about the potential for assessments to be misused, from labeling students inappropriately to parents who might be worried about giving a measurement to their child’s emotions. While McKown said there’s not a lot of evidence that these things are currently happening, Hamilton added that it’s important to make sure educators have training on how to appropriately assess students on social-emotional competencies and how to use the data.

“Many [SEL skills] actually are measurable with the same level of precision that you can measure a reading skill or a math skill. Not all of them, but some of them.” McKown said. “They’re not as soft as you might think.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)