Mississippi Used Corporal Punishment in Schools 4,300 Times Last Year

Here’s what districts are doing to change that

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Shortly after moving to Madison, Jamie Bardwell learned that the Madison County School District requires parents to opt out in writing from corporal punishment being used on their children, a fact she discovered from other students talking about it in her son’s class.

“A kid got paddled, came back and told my son, and my son was terrified,” she said. “I explained to him that that would never happen to him, we’ve written this letter, but it’s really scary for kids to have people in their classroom come back with these stories. Even if your kid isn’t the one who is subjected to corporal punishment, they’re still being impacted by it.”

The Madison County School District told Mississippi Today that corporal punishment is an option in the district, and that parents are always consulted before it is administered.

The U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights tracks corporal punishment data in public schools nationally, which is generally defined as the use of physical force to discipline students. Often called paddling, the term stems from using a wooden paddle to hit a student on the butt.

Federal data shows that over the last decade, Mississippi had more corporal punishment incidents than any other state for every year data was collected. In the 2017-18 school year, the most recent year for which there is federal data, nearly 30% of all incidents occurred in Mississippi. In the same year, 22 states reported at least one incident of corporal punishment and 10 reported over 1,000 instances.

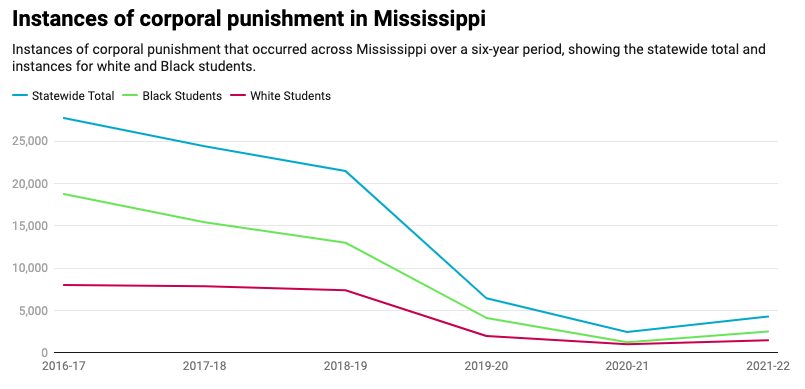

The Mississippi Department of Education has more recent data, also for public schools. Instances of corporal punishment fell by over 23,000 from the 2016-17 school year to the 2021-22 school year. School leaders attributed this to a combined influence of the pandemic and a 2019 state law which banned the use of corporal punishment on a student with a special education classification.

Some districts began the work of rethinking discipline models before the 2019 law passed.

William Murphy, director of student affairs for the Sunflower County Consolidated School District, said the district’s process of veering away from corporal punishment started in 2016 with restorative justice trainings, a practice that seeks to repair harm caused rather than focus on punishment. When the 2019 law passed, Murphy said multiple administrators told him they rarely utilized it anyway “just because of the lack of effect that it was having.”

He acknowledged that the decline, from 400 incidents in 2016 to 22 in 2022, was impacted by the pandemic and students not being physically in school. However, he said he doesn’t expect to see a return because of the emphasis the pandemic put on social-emotional learning.

“The pandemic allowed us to see into some children’s homes, to see some things that we might have not been privy to before,” Murphy said.

“When you’re having to do more home visits or get closer acclimated to students at home, you learn some things that I think will make you less likely to use corporal punishment,” he continued. “When you learn that a child might have been abused or that a home situation is particularly traumatic, I just think there’s a push to do more counseling, more talking.”

In the Scott County School District, Assistant Superintendent Chad Harrison said the district’s decline in corporal punishment was strongly linked to the 2019 law going into effect. Concerned that a teacher would mistakenly administer corporal punishment to a special education student, the district changed its policy so that it can only be used by administrators or administrative assistants. The district went from nearly 1,800 incidents in 2016 to 532 in 2022.

Harrison also said that the district has focused more energy on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, a framework which seeks to reward students for positive behavior rather than penalize them for negative.

Valeria Wilson, the behavior specialist for the district, explained the shift includes both creating a culture of rewards for all students and developing individualized plans for students who are struggling with behavior problems.

At every school, teachers, cafeteria workers, janitors, and front desk employees all have “bucks” that they can give students to reward behaviors like being respectful or paying attention. Students use the bucks to buy snacks or gain entry to celebrations throughout the year.

When students are put on a behavior plan, Wilson works with the student and a committee to develop daily goals and rewards if the student meets them. As a part of the plan, an adult checks in with the student daily to discuss their behavior and provide instant feedback.

“It’s just simply making them aware of their actions,” Wilson said.

Wilson also said that students are involved in the process of selecting their rewards in order to better motivate them.

“You have to find out what the interests of that kid are, and you can only do that by building relationships with them, and then you build your plan around that student,” she said.

Despite the shifts toward other discipline models that some districts are making, advocates are concerned that corporal punishment numbers will tick back up.

Ellen Reddy, executive director of the Nollie Jenkins Family Center in Holmes County, said she believes the pandemic accounts for some of the decline, but is also concerned districts are not being monitored properly.

The Nollie Jenkins Family Center released a report in 2021 highlighting significant disparities in corporal punishment reporting data between the Mississippi Department of Education and the federal government. Jean Cook, communications director for the Mississippi Department of Education, said MDE could not explain these differences, but that districts are not required to respond to any data quality questions from the federal government. A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Education did not respond to questions regarding their validation process.

When asked how MDE verifies its own data, Cook said districts are required by state law to report accurate information to the state’s data management system and, in doing so, verify their monthly data reports before submitting them to the department. The department does not independently verify this data after it is received unless a complaint is filed.

When talking about the decline of this practice in Mississippi, Reddy and her associates expressed concern about the demographic profile of the students who are still receiving corporal punishment, as national research has shown corporal punishment is disproportionately used on Black students.

“Any student that experiences it is one student too many, so who’s still left in that category, what do they look like, and why are they still experiencing it?” asked Chanya Anderson, a data analysis consultant working with the Nollie Jenkins Family Center. “Because if you’re talking about such a drastic decline, what is it about those students that you still feel the need to use corporal punishment if your model has now shifted to something else?”

MDE data shows that for the 2021-22 school year, nearly 60% of corporal punishment instances were administered to Black students, while 35% happened to white students. For the same school year, 47% of K-12 students were Black and 43% were white.

Anderson also said that laws temporarily put a damper on certain practices, which could explain the decline in corporal punishment incidents.

“When you enact any law, even if laws don’t affect all populations … that’s still going to bring attention to the plight of corporal punishment generally,” Anderson said. “In light of laws, you will often see institutions pull back momentarily, and then as people forget about it and move on, they’ll start to increase their usage of it again once the spotlight has moved off the topic.”

This legislative session, Rep. Carl Mickens, D-Brooksville, introduced a bill to ban corporal punishment but it died, as have his previous efforts for the last five years. Mickens said he doesn’t think the practice “will cause a child to learn, I think it might cause them not to want to learn.” Though he disagrees with the practice, he said ultimately only legislative leadership has the power to decide if a bill progresses.

Rep. Richard Bennett, R-Long Beach, chair of the House Education Committee, said he has not taken up the bills to ban it because he believes corporal punishment is a local issue. He said he has not looked at research on how it impacts children.

Studies have shown that corporal punishment can lead students to be more aggressive, have higher rates of depression, and perform worse in school. Morgan Craven, federal policy director for the Intercultural Development Research Association, said it’s telling that so many groups have lined up in opposition, including psychiatrists, pediatricians, lawyers, public health officials, school counselors and educators.

“Not only is it ineffective, but it can actually make issues worse,” Craven said. “Whatever it is that is leading to a particular behavior, it is not solved by hitting a kid.”

Francine Jefferson, who was a board member of the former Holmes County School District, advocated to end corporal punishment when she was on the board from 2010-2018. While she did not achieve a complete ban, the board did change policies to restrict the practice, including allowing parents to opt out.

“I grew up in that environment where teachers are allowed to paddle the kids. I mean, hell, the bus drivers could paddle you, everybody could paddle you,” Jefferson, who also grew up in the district, said. “I grew up with that experience, and it wasn’t a pleasant one … That’s why I pushed so much for it because I never forgot that experience.”

The district later banned the practice entirely in 2018 after consolidation, but Jefferson said she is still concerned about it happening in Holmes County and other parts of the state.

“How many pounds of pressure do you put on a child’s bottom?” she said. “What’s the right amount? Nobody knows. If you can’t tell me that, then I don’t think you need to do it because you can’t take it back.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)