Minnesota Supreme Court Takes School Desegregation Case to the Kids

Justices hear oral arguments at Twin Cities HS that could be impacted by decision in long-running lawsuit — and take questions from students

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

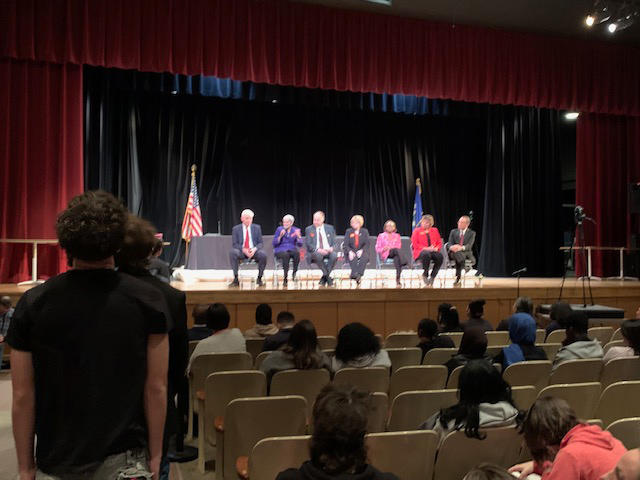

Twice a year, as a real-life civics lesson, the Minnesota Supreme Court hears oral arguments in a high school in front of an audience of students. After the justices dispense with the docket, they take off their robes and talk to the kids.

And so it was recently that seven jurists found themselves on the auditorium stage in a midcentury brick school a few blocks outside Minneapolis, hearing a desegregation case that could have tectonic ramifications — including for Richfield High School.

The question at hand: The U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board decision declared de jure — intentional, state-sanctioned — segregation to be unconstitutional. But what about de facto segregation, which in Cruz-Guzman v. State of Minnesota focuses on schools that are nearly entirely single-race because families of color have sought welcoming places for their children?

And what about places like Richfield, where Associate Justice Paul Thissen’s mother once taught? While the neighborhood was once home mostly to working-class whites, today, the school’s enrollment is 75% students of color and 65% low-income.

If the plaintiffs win, Richfield will have to enroll a different student body, Thissen said in posing a question to one of the lawyers arguing before him: “But there’s no other high school to go to in this district. What are they supposed to do?”

In the eight years since it was filed, Cruz-Guzman v. State of Minnesota has been the subject of a long, stalled mediation, two trips to an appellate court and, now, two trips to state Supreme Court. It’s nowhere near ready for trial.

Sitting alongside a Who’s Who of state officials, some 600 students watched silently throughout the hour-long hearing. It was a fast-paced drama, as the justices interrupted attorneys with pragmatic questions about desired outcomes and intellectual puzzles about the meaning of the state Constitution’s education clause.

If the debate among the attorneys was intense and seemingly irreconcilable, the students who lined up to question the justices after the hearing were equal parts hilarious and prescient.

“My question is for this lady in pink — gorgeous, by the way,” said Niya Briggs, the first teen at the mic, gesturing at Associate Justice Natalie Hudson and her vivid, two-tone jacket: “How do you guys get into this sort of thing?”

Hudson’s response: Go to law school, get a liberal arts education and make sure to take classes that will teach you to write.

A long line formed while she was answering.

What do you do when the language in the Constitution doesn’t directly address the arguments before you? Or if you do not personally agree with it?

Do you have a judicial philosophy, such as being a constructivist?

Do you take into account the changing values of younger generations?

Chief Justice Lorie Skjerven Gildea had cautioned the students that the judges couldn’t take questions about the case being heard that day, but one asked anyhow, explaining that she and her friends were confused. As Gildea demurred, it was easy to imagine their confusion.

The state Constitution’s guarantee of an adequate education — the actual words are “general and uniform,” a phrase that is often described as an adequacy clause — lies at the heart of the case. The plaintiffs are several Minneapolis and St. Paul families who want the justices to decide the case in their favor before it goes to trial by agreeing that racially imbalanced schools are by definition inadequate.

During the oral arguments, the state’s attorneys countered that schools and districts determine the quality of the education their students receive; nothing in the state Constitution or legal precedents requires a racial balance.

Several charter schools are participating in the case as intervenors because the remedy the plaintiffs seek could force them to enroll a cross-section of students, rather than taking all comers — regardless of their racial or socioeconomic background. This, they say, would devastate a number of small, culturally affirming schools where a majority of students are of a single race or ethnicity and are flourishing.

What Brown v. Board outlawed, their attorneys argue, is different from the current situation. The 1954 decision ruled that barring students of color from the same schools as white children violated the Equal Protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.

It’s not segregation, lawyers for the charter schools argued, when a family chooses a school for its children. Minnesota charter schools are required to admit students by lottery when there are more applicants than seats, so a school can’t exclude anyone based on race, class or ability.

The justices seemed unconvinced that the plaintiffs had established a relationship between integration and an adequate education. One asked repeatedly whether the case should be sent back to the trial court so that question might be probed in front of a jury.

Among the last questions posed by the students were a couple suggesting that, complicated though the proceedings were, the kids were listening:

When both sides make good arguments, how do you decide?

How can someone my age get involved?

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)