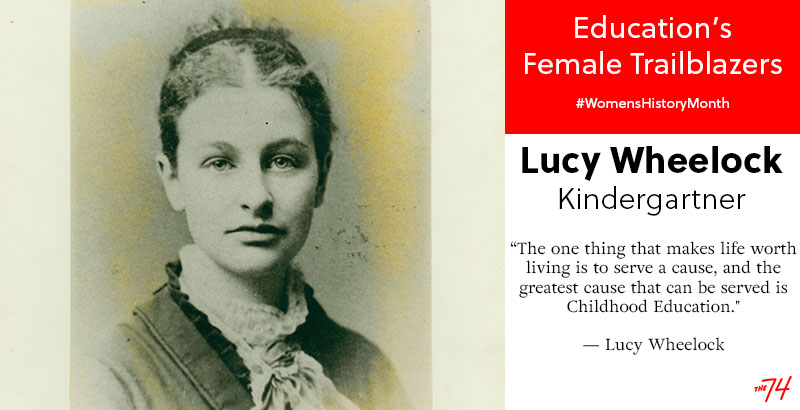

Meet Lucy Wheelock: How an Early-20th-Century Educator Saved Kindergarten for Generations of U.S. Kids — & Founded Her Own College

March is National Women’s History Month. In recognition, The 74 is sharing stories of remarkable women who transformed U.S. education.

Kindergarten has arguably been the most successful education reform in U.S. history. But it almost didn’t happen.

Its survival is owed in large part to an educator named Lucy Wheelock. As the 20th century dawned, the movement to expand education to 5-year-olds started to fissure over the most appropriate way to teach young learners. Wheelock was one of the heroes who held all the pieces together.

“The kindergarten is a big deal: It’s one more year of life added to what public taxpayers pay,” said Barbara Beatty, professor and chair of Wellesley College’s department of education. “There are lots of reforms in education, but many wither away; they don’t take. Lucy Wheelock was one of the people who helped the kindergarten take.”

Much of this can be attributed to Wheelock’s great gift as a compromiser and moderator, Beatty said. Wheelock helped navigate the growing divide between practitioners of the traditional model of kindergarten, adopted from Germany, and proponents of developmental psychology who criticized those methods.

Wheelock was born into a middle-class family in 1857 in Vermont. She graduated from high school and had ambitions to attend Wellesley College, but she didn’t feel prepared. A visit to a kindergarten classroom changed her life, though, convincing her to become a “kindergartner,” the name at the time for kindergarten teachers. Instead of attending college, she enrolled in a kindergarten training school. Her diploma was signed in 1879 by Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, who founded the first English-language kindergarten in the U.S.

Throughout Wheelock’s career as an educator, she served as president of the International Kindergarten Union, and she created her own early educator training school, Wheelock College in Boston, which this year will merge with Boston University.

“The one thing that makes life worth living is to serve a cause, and the greatest cause that can be served is Childhood Education,” Wheelock wrote in her unpublished autobiography.

The concept of kindergarten, a system of learning for young children centered on the idea of play, was invented by German educator Friedrich Froebel. He opened the first school in 1837 and stocked it with play equipment of his own invention, like small weaving patterns and minuscule blocks with specific directions for how children should assemble them. His methods drew a fervent international following.

Kindergarten was brought to the U.S. by German immigrants who began teaching Froebel’s approach in Wisconsin. Educators then began opening English-language kindergartens, the first of which was founded in Boston by Peabody in 1860. This was followed by Susan Blow, who opened the first kindergarten associated with a public school in 1873 in St. Louis.

But a few decades later, as the study of developmental psychology grew popular in the U.S., researchers like G. Stanley Hall criticized Froebel’s specific play methods as too didactic and developmentally inappropriate for young learners. While developmental psychologists encouraged play, they felt young children couldn’t handle the very fine motor skills needed to use Froebel’s instructional toys.

The science didn’t sit well with some kindergartners, who had a cult-like devotion to Froebel’s methods. As educators started advocating for the adoption of kindergarten in public schools across the U.S., tensions swirled over what kind of instruction should take place in these classrooms. Hall and education philosopher John Dewey criticized traditional kindergarten as being too structured and overly emphasizing symbolism, or learning life lessons through play. Dewey even said Froebel wouldn’t have expected his followers to adhere so literally to his ideas. But the St. Paul Globe, in favor of Froebel’s traditional methods, called these criticisms “rankest heresy.”

Wheelock was one of the few who tried to bridge this divide. She brought educators to Hall’s psychology labs, where he discussed developmental psychology with them. At the same time, she led teachers on a Froebel pilgrimage in Germany to explore the revered kindergartner’s world.

Regardless of the split, the idea of teaching 5-year-olds was catching on, for reasons ranging from setting children up for better academic success to Americanizing immigrants to lifting families out of poverty. Still, selling policymakers on kindergarten required both money and passion, which is why walking the line between the older, wealthy, traditional kindergartners and the younger, politically active ones was critical. As both president and a member of the International Kindergarten Union, Wheelock co-authored a report that helped carve out this middle territory.

“Discussions are profitable; but dissension is not so,” Wheelock wrote. “May we not rally for the preservation of the kindergarten as a distinctive type of education practice?”

Wheelock had a captivating personality that helped her forge a middle ground between the warring groups. A newspaper at the time described her as magnetic, with a charming personality. She was calm but gifted at speechmaking. A student of hers described her as having a power over the people she instructed: “She inspired everyone and we felt that we wanted to go out and do things in the world.”

It wasn’t easy being the peacemaker, and this work took its toll on Wheelock, California State University professor Catherine C. DuCharme wrote. Not everyone was convinced by her moderation efforts — and some still called her a heretic for straying from Froebel’s specific methodology.

But history has proven the success of her work. Other women were able to build upon Wheelock’s efforts, like Bessie Locke, who capitalized on the power of the media and wealthy donors to widely share one of Wheelock’s core beliefs: the importance of kindergarten in tackling the cycle of poverty.

Wheelock believed that a child’s education could lift up an entire family from poverty, and today, research shows the value of a high-quality education for early learners from low-income backgrounds. The landmark 1960s Perry Preschool Study found that children who grew up in poverty but attended a high-quality preschool were more likely to have graduated from high school and landed a high-paying job than those who did not, and they committed fewer crimes.

Although today, only 15 states and Washington, D.C., have laws mandating that students attend kindergarten, early education is much more common than it was in the beginning of the 1900s (in 2015, 87 percent of 5-year-olds were enrolled in school). Still, the way kindergarten operates is very different from what Froebel, Wheelock, or other early educators envisioned, said Diane Levin, professor of early-childhood education at Wheelock College. Play-based learning is far less common, as schools try to implement traditional academic instruction at an early age. But research shows that play-based learning for young students is still critical to their development and even helps achievement in the long run.

Today, educators at Wheelock College instruct their teachers-in-training to support children’s skill development through play. But this can prove challenging — Levin remembers one former student calling her after a principal yelled at her for teaching her kindergarten students the alphabet by using a ball.

“Lucy would not be happy that things are like this now, but she also was very much into thinking about how can we work with children to best meet their needs, given their circumstances,” Levin said.

Or, as the passionate, mission-driven Wheelock might say, never give up the good fight.

“The goal is nothing less than the redemption of the world through the better education of those who are to shape it and make it,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)