‘Media Literacy Is Literacy’: Here’s How Educators and Lawmakers Are Working to Set Students Up for Success Online

Updated April 8

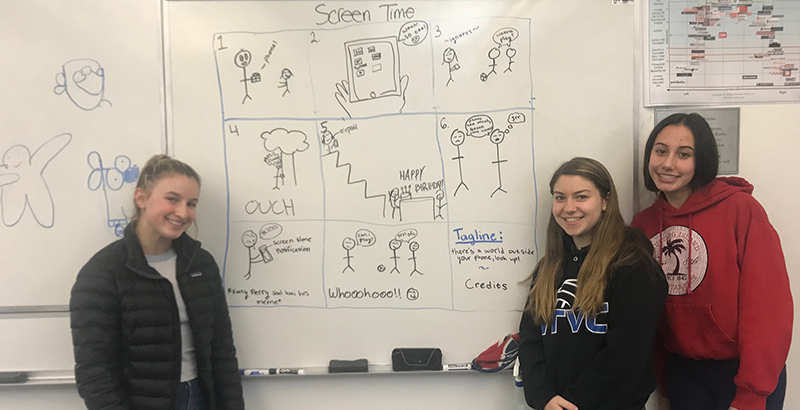

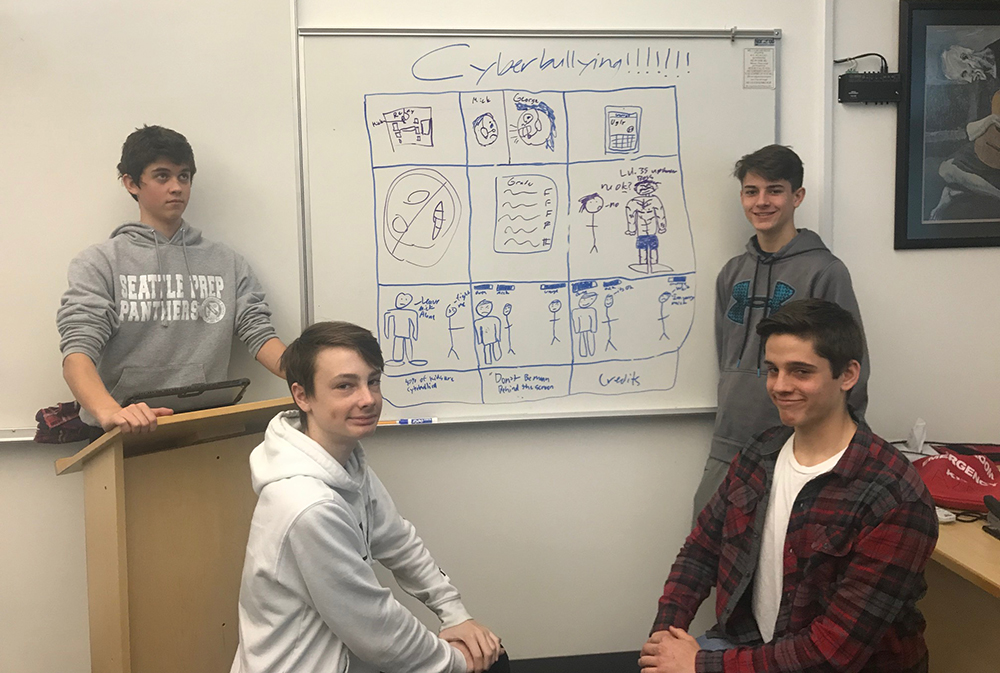

Michael Danielson gives students in his ninth-grade media literacy class a simple piece of homework each night: Pay attention.

The assignment is meant to prod them into thinking critically about the countless messages that bombard them every day. They report back to their teacher and classmates at the start of each class with “media literacy moments,” explaining how they discovered hidden motives and attempts to manipulate them or sell them products.

Seeing his students apply five core concepts about media to what they see on Netflix, at the movies and online is Danielson’s favorite part of his job. It’s how he knows he has altered the way they consume media.

“I’ve changed them for life,” he said.

Danielson teaches at Seattle Preparatory School, a private Catholic high school. In addition to the required one-semester media literacy class, he teaches yearbook and theology classes and advocates for media literacy as chair of Action 4 Media Education, a Washington state-based group.

Media literacy is a broad term that encompasses a wide set of skills ranging from thinking critically about news and opinion articles to dealing with cyberbullying to creating and sharing content online. The idea of media literacy is not new, but experts say it gained new momentum following the 2016 presidential election.

Across the country, lawmakers, educators and advocates are working to elevate the issue of media literacy in legislatures and schools. Washington state has been at the forefront of the movement.

In 2016, lawmakers in Washington state passed a bill with bipartisan support that created an advisory council to study media literacy and make recommendations to the legislature based on its research. The following year, legislators passed a law — based on the council’s recommendations — requiring the state superintendent’s office to survey educators and district officials about the state of media literacy in schools across Washington. Now, lawmakers are considering a bill that would provide grants for educators to create curriculum for media literacy and to allocate money for the state Department of Education to hold two conferences on the subject.

The initial Washington measure to create the advisory council is now the basis of a model bill used by Media Literacy Now, a nonprofit organization that advocates for media literacy, to help lawmakers get the topic on the agenda in their states.

Other states have taken their own approaches to making media literacy a priority, some more forcefully than others. For example, California lawmakers passed a law that requires the state Department of Education to provide a list of media literacy resources on its website by July 1. In a stronger move, Minnesota in 2017 added “digital and information literacy” to its required K-12 education standards.

Why now

Media Literacy Now is currently tracking 15 bills in 12 states. The bills range from advisory council proposals to measures that would create grant programs for media literacy specialists or add media literacy to state curriculum guidelines.

Research indicates students need help evaluating the information they find online.

In 2015 and 2016, researchers at Stanford tested more than 7,000 K-12 and college students on media literacy and found that, although they spend lots of time online, students were not as proficient in media literacy as the researchers expected or hoped.

One of the activities assessed whether middle school students could distinguish between news articles, sponsored content and advertisements on a website’s homepage and how they evaluate the credibility of social media posts.

“In every case and at every level, we were taken aback by students’ lack of preparation,” the authors wrote.

One of the researchers, Joel Breakstone, told The 74 that increased concern about fake news is part of the reason for the rising interest in media literacy.

“I think that the last two election cycles have suggested the dangers, the substantial dangers of problematic information being spread online,” Breakstone said. “And it has potentially really negative consequences for the way in which our democracy functions.”

Breakstone and his team’s research and subsequent creation of classroom materials have focused on the civic aspect of media literacy and how it affects people’s decisions related to social and political issues.

“This is not a partisan issue,” he said, adding that neither side “has a monopoly on spreading problematic content.”

Students seem to be lacking the skills they need to navigate the vast amount of information online, but many adults need help, too. A 2018 study by the Pew Research Center found that younger people were better able to distinguish facts from opinion statements than older people. A separate study in 2016 found that people over 65 were far more likely to share fake news on Facebook than younger age groups.

What states are doing

Rep. Lisa Cutter, a Democrat elected to the Colorado state legislature in November, was on vacation in Mexico late last year thinking through what her legislative priorities would be.

“It popped into my brain: media literacy,” she told The 74.

Cutter, who previously worked as a public relations consultant, said she has always valued the media.

“I’ve always been idealistic about the power of communications,” Cutter said. “I’ve been a big fan of the media, truly, and the benefit [it brings] to a democracy and to our society.”

Cutter introduced a bill that would create an advisory council similar to the one in Washington.

The original measure met some resistance in the education committee, of which Cutter is a member, over who would be on the committee. Cutter wanted the council to include teachers and librarians who are members of professional organizations, which might include teachers unions, but Republican members said having union members on the council could create a conflict of interest. Cutter tweaked the language of the bill to address this concern, and the bill advanced out of the committee and is now being considered by the appropriations committee.

Cutter hopes this will eventually lead lawmakers to add media literacy to state education standards, which provide guidance for school districts.

Similar laws have been passed previously in Rhode Island and Connecticut, and lawmakers are considering comparable measures in seven other states. The New Mexico legislature this year passed a version of the bill, which is now awaiting the governor’s signature.

The main goal of the model bill is to get media literacy on the policy agenda at the state level, said Media Literacy Now’s founder and president, Erin McNeill.

“It’s a good first step,” McNeill said. “It’s a structure that allows the state and experts and stakeholders to work together to figure out solutions.”

Breakstone agreed that the advisory council model is a good first step but said it should be just that — a first step.

“I think that we can’t delay too long,” he said. “The consequences are too dire to put it off with years of committees. So there’s a balance to strike there, of a need to be deliberate in making a well thought-out and manageable plan. On the other hand, we can’t dither given the stakes at play.”

‘Media literacy is literacy’

Some advocates and educators are working on more direct ways to reach teachers and children and invest in media literacy.

The Knight Foundation, which supports journalism, recently gave a $5 million grant to the News Literacy Project, started in 2008 by journalist Alan Miller, to expand its online course for middle and high school students and increase its professional development opportunities for librarians and teachers. The grant is part of a broader $300 million effort by Knight to bolster local news over the next five years.

The public radio station KQED in March rolled out a new microcredential program open to teachers across the country that will provide teacher training in media literacy. In partnership with PBS, KQED will grant a media literacy certification to teachers who complete the free, competency-based online program.

KQED already supports media literacy with two websites, KQED Teach and KQED Learn, but Randy Depew, the San Francisco-based station’s managing director of education, said he and his team realized many teachers needed to sharpen their own media literacy skills.

“The certification was born out of this idea of being able to provide a road map for teachers so that they could see, What are those skills that I need in order to be able to call myself media literate?” he told The 74. “And then at that point our belief is that if we can level up teachers, then the classroom activity will follow.”

Depew added that he expects that what’s now known as media literacy — consuming and creating blogs, podcasts and other digital content — will eventually be “folded into” literacy itself and considered essential skills for all students.

“If we want what’s best for our students, then we have to make sure they can read and write with media,” he said.

Experts agree that adults and students both need help learning to navigate the information landscape online.

“Media literacy is literacy in the 21st century,” McNeill said.

This article has been updated to clarify a quote by Media Literacy Now’s Erin McNeill.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)