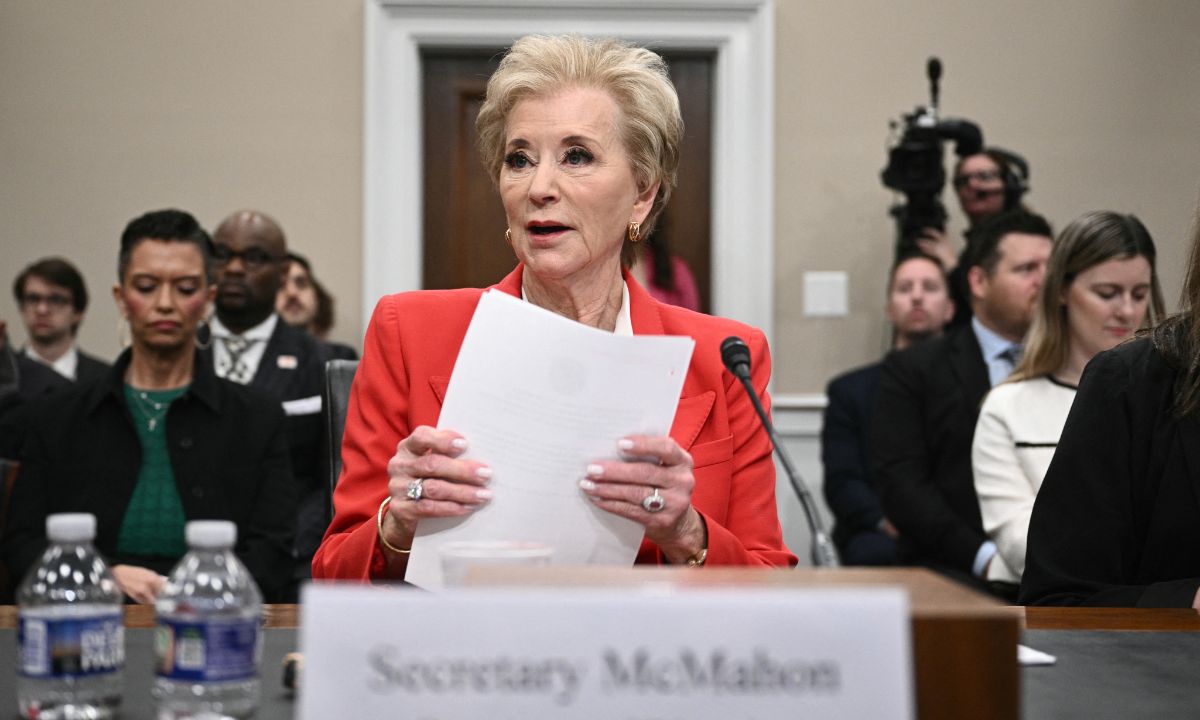

McMahon Takes Flak From Democrats, Republicans at Congressional Budget Hearing

The education secretary on Wednesday argued for deep cuts to K-12 programs, but one committee leader said she’s 'incapacitating' the department.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Education Secretary Linda McMahon defended a 15% cut in education funding Wednesday as she faced skeptical members of Congress on both sides of the aisle.

For over two hours, she fielded questions on a “skinny” 2026 budget that lacks details on how the administration would shrink $4 billion for K-12 programs into a $2 billion block grant for states. She drew sharp words from the ranking Democrat for canceling funding for school mental health professionals and grants to train teachers.

“By recklessly incapacitating the department you lead you are usurping Congress’s authority and infringing on Congress’s power of the purse,” said Connecticut Democrat Rosa DeLauro. The current budget, she said, “was passed in the House, was passed in the Senate — civics 101 — and the president signed it. It’s the law of the land.”

At least one Republican also questioned McMahon about why the department is recommending a $1.6 billion cut to programs intended to help more poor and minority students get into college.

“It is one of the most effective programs in the federal government,” said Rep. Mike Simpson of Idaho, referring to TRIO, a package of eight programs that encourage connections between colleges and K-12 schools.

McMahon would also cut GEAR UP, a college readiness program that targets low-income students beginning in middle school. She cited an anecdotal report of TRIO funds covering the cost of a trip to Disney World.

“I’m not sure that all the expenses in TRIO should be there,” she said, but added that if colleges and universities aren’t reaching out to K-12 schools on their own, they should be.

‘Bare minimum’

While past secretaries have called for cuts in funding, none have presented a budget in the midst of such aggressive attempts to eliminate the department. The proposed cuts, she said, represent a desire to cut bureaucracy, end “federal overreach,” and give states and parents more control over education. Despite cutting over half the staff, she said employees who remain “haven’t missed a beat” in implementing the programs they’re charged with overseeing. She stressed that there are no plans to cut Title I grants to low-income schools or funding for students with disabilities.

“Democrats tried to tie proposed budget cuts to ending the department and, somehow, ending all public education,” said Neal McCluskey, director of the libertarian Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom and a proponent of funding private school choice. “But the secretary handled that very well, making clear that the goal is to cut bureaucracy and federal controls in order to improve education and adhere to the Constitution.”

But others say the overhaul has created confusion and chaos. States and districts nationwide are still waiting on details of how much in Title I funds they can expect to receive this fall — a delay that complicates hiring and budgeting decisions.

“We have not received any guidance from our state department of education,” said Jeremy Vidito, chief financial officer for the Detroit Public Schools Community District. Regardless of any cuts at the federal level, his district has promised not to lay off staff. But a delay of six months or more,” he said, “would lead to cash flow issues that we would have to manage.”

Last week, Democrats in the House and Senate sent McMahon a letter, laying out the ways they believe her department is stumbling — from giving districts compressed timelines for grant applications to abruptly ending funding that schools depend on.

“We were told your department’s work would be efficient, particularly after the reduction in force,” they wrote. “But that does not appear to be the case here.”

The department has not responded to questions about when it will release the remainder of funds for the current federal fiscal year, which expires at the end of September. But McMahon repeatedly told the committee she would follow the law.

“That is the bare minimum of what the American people should expect from a federal agency tasked by Congress with serving our nation’s children,” said Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union, who sat just behind McMahon during the hearing.

What bothered Rodrigues most was McMahon’s admission that Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency made the decision to cut roughly 1,300 staff members. She just carried it out after she was confirmed and said she has little knowledge about the backgrounds of the DOGE staff that Rodrigues said are “wielding extraordinary power within the agency,”

The department has since hired back 74 staff members who were fired, McMahon said.

Eric Duncan, director of P-12 policy at EdTrust, which advocates for programs that improve educational equity, noted that McMahon aims to cut programs that received support from both sides of the aisle.

“We were encouraged by the critical feedback on the department’s decision to cut school mental health grants,” he said. “Cutting these funds risks bipartisan priorities: improved mental health supports increase school safety and improve academic outcomes.”

In one tense exchange, Rep. Madeleine Dean of Pennsylvania, a Democrat, asked McMahon if she’s ever met with students who survived school shootings, like in Uvalde, Texas, or Parkland, Florida.. The secretary said she had only met with parents from Sandy Hook because she’s from Connecticut.

“Do you plan to do that?” Dean asked about meeting with students. “How soon can you do that?

“I’ve got a lot of responsibilities,” McMahon said.

‘Lost the fundamental basics’

Aside from Simpson’s concern about college readiness programs, most GOP members of the committee commended McMahon for her efforts to downsize the agency and elevate school choice.

“Thankfully some states have pursued choice options for students whose traditional public schools have not served them well,” said Republican Robert Aderholt of Alabama, who chairs the subcommittee on education.

Prioritizing choice and giving states more control are two of the three goals for any future grant programs she laid out in a Federal Register posting Tuesday. The third is improving literacy.

“We have seen such decreases or failing in our schools because we are not teaching our children to read,” she said. “We’ve lost the fundamental basics, and I want to see our schools return to the science of reading.”

DeLauro, however, listed a federal literacy grant program, which provides up to $14 million to states to improve reading skills, especially among low-income students and English learners, as one of the 18 “unspecified programs” potentially on the chopping block.

“A block grant is a cut. All of my colleagues here know that,” she said. “The states cannot afford to pick up the slack.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)