Massachusetts Moves to Bring Sex Education Out of the ‘90s

Dual pushes from educators and legislators target inclusive, comprehensive sex ed

Massachusetts’ sexual health curriculum remains stuck, at least on paper, in the Wild West educational landscape of 1999. But after some 24 years, and with more than a decade of pressure from advocates and a cohort of legislators, the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education is getting ready to make some changes.

What those changes are remains a mystery. There are broad state standards for health education, promulgated through the department, but they were last updated decades ago and allow for a wide amount of leeway in school-by-school choice in what curriculum and materials to use.

A 2018 review from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s Office of Sexual Health & Youth Development found 43 percent of high school students were not taught about condoms at school and 61 percent reported not talking with a parent about preventing HIV, sexually transmitted infections, or pregnancy. While the state teen birth rate declined along with the rest of the country, the 2018 report found that sexually transmitted infections rose across age groups and especially in the 15- to 24-year-old range.

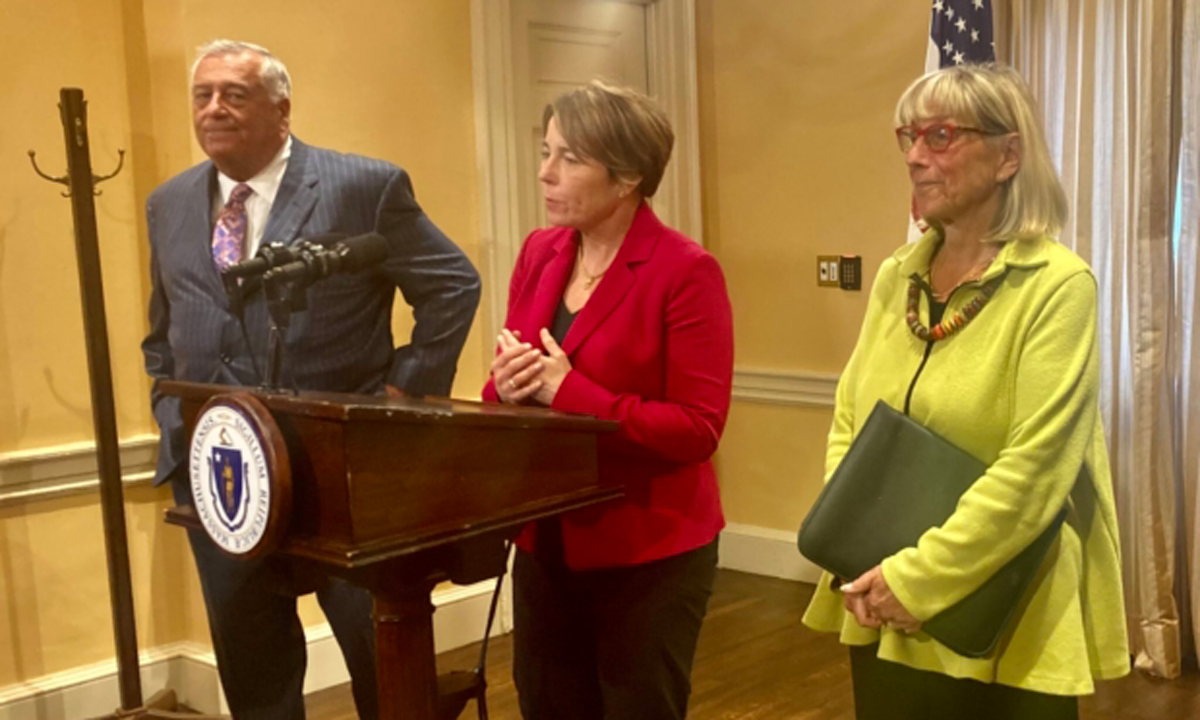

“Governor Healey supports efforts to make sure that sex education offered in Massachusetts schools is comprehensive, inclusive, medically accurate, and age appropriate,” spokesperson Karissa Hand said in a statement. “Our administration is also working with DESE to put forward a health education framework that achieves these goals.”

A DESE spokesperson confirmed the agency is at work on the framework, but did not say what the timeline is for the update. Efforts to revamp the state health standards were in progress before the global COVID-19 pandemic hit, which paused the process until recently.

“Following stakeholder engagement, revisions are being reviewed by the new administration,” said education department spokesperson Jacqueline Reis. These stakeholders included experts within particular topic areas, colleagues from other state agencies that focus on public health and mental health, and advisory councils to the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, Reis said.

With little to no visible movement on the DESE side for years and frustration mounting, lawmakers have been pushing for a plan B: setting requirements for new standards through legislation and making sure that the education department moves more quickly in the future. But that effort has also been slow going on Beacon Hill.

For a dozen years, a consistently re-filed sex education bill requiring schools that offer sexual health programming to “provide a medically accurate, age-appropriate, comprehensive sexual health education” with an emphasis on consent and acknowledging LGBTQ+ identities stalled out on Beacon Hill. For the past four years, the “Healthy Youth Act” passed the Senate only to fizzle in the House. It would not require any school to offer such a course, just ensure a baseline for the content covered.

“We would be saying that we believe in the right of young people to receive fact-based information in their sexual health education,” said Jennifer Hart of the Planned Parenthood League of Massachusetts. The erratic landscape of sex ed programs across the state currently leaves some young people “getting incorrect information that is based in fear and stigma and shame” in their public institutions, Hart said.

Supporters say the bill is “common sense” updating to reflect a healthy and informed approach to sex education.

“Really, in my mind, I don’t understand why it’s taken this long,” said Sen. Sal DiDomenico, of Everett, who refiled the bill in the state Senate this term. “There’s no mandate here. It just says if they are teaching sex education, it has to be appropriate, medically accurate, and inclusive. I’m sometimes confused about where this controversy comes from.”

Parents, he notes, would still have the choice to opt out as they do now, receiving a letter at the start of the year giving them notice.

Opponents of the bill and similar policies argue that exposure to these curricula will encourage sexual activity among young people and disempower parents from determining the best time and manner to educate their children about sex.

“Parents could still opt out their children. But what good would it do?” asked Mary Ellen Siegler in a post for the Massachusetts Family Institute, a non-partisan public policy organization that emphasizes Judeo-Christian values, during a prior attempt to pass the act. “With the amount of sexually explicit (and gross) material included in the curriculum, children everywhere in school would still be exposed to Comprehensive Sexuality Education material. Conversations among students are bound to sink to the level the scenarios suggest.”

The opt-out has become a friction point for LGBTQ+ advocates. Tanya Neslusan, executive director of MassEquality, said the organization is no longer part of the Healthy Youth Act coalition because the bill would allow individuals and schools to opt out.

“We’ve been dealing with anti-LGBTQ battles across the state and seen a real increase over these last few years in coordinated opt-out campaigns,” she said. The campaigns have been focused on individual parents pulling their children out of programming that discusses LGBTQ+ identities in particular, she said.

“We really are afraid that to push through the Healthy Youth Act legislation – even though it’s great legislation and it’s what we need – without a mandate in place to have sex education, that some districts will end up with no sex education at all,” she said.

MassEquality is now backing a bill put forward by Rep. Marjorie Decker, of Cambridge, which mandates statewide age-appropriate and medically accurate sex education, though parents are still permitted to opt their children out of any portion of the curriculum. Though the Decker bill’s “wording around health education is a bit vaguer” and does not specifically touch on LGBTQ+ orientations or consent, it does require that sex education adhere to national standards, which covers much of the Healthy Youth Act’s priorities, Neslusan said.

Of the opt-out provision, DiDomenico said, “it’s just a matter of trying to get something passed in this space right now, and that option is important for some folks.” He added, “I would be okay with a mandate, but I have to get my colleagues to agree.”

The act would make sure the state avoids 25-year gaps between updates, at least. It requires DESE to review and update its standards to be consistent with the Healthy Youth Act at the passage of the law and then at least every 10 years afterward.

Out-of-date standards are one thing to tackle, Healthy Youth Act supporters say, but current regulations also leave a lot of discretion up to the individual schools as to the content of the health curriculum. Under the act, DESE must collect information on the sexual health programs offered by schools across the state.

Jamie Klufts, a co-chair of the Healthy Youth Act Coalition, wrote in an opinion article that new data on youth risk behavior from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention underline the need for consistent and comprehensive sex education programming.

While reported sexual assault of young women is up to almost one in five nationally, condom usage among youths is down from 60 percent in 2011 to 52 percent in 2021. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people experience more sexual violence than their heterosexual peers and are nearly four times more likely to report suicide attempts.

Over the decade covered by the report, the Healthy Youth Act has not come to the Massachusetts House floor for a vote.

“This means that an entire generation of young people has gone through our school system without the assurance of quality sex and relationship education that the Healthy Youth Act would provide,” Klufts and her co-authors wrote.

The state of the Commonwealth’s sex ed standards is particularly disheartening, advocates say, because in a post-Roe United States, prominent Massachusetts politicians have taken a particular pride in codifying reproductive care protections into state law but left sexual health by the wayside.

Planned Parenthood reviewed all 50 states plus Washington D.C. and ranked their sexual health curriculum and their level of abortion protections. Massachusetts is somewhat of an outlier among states that are “protective” or “very protective” of abortion care, Hart said, because the state standards for sex ed do not require education to be medically accurate, cover birth control options, include LGBTQ+ identities, or affirm abortion access.

“Sex education is comprehensive,” Hart said, “and still there is shame and stigma around sex ed, around abortion. In Massachusetts, we have such protections for sexual reproductive health, and this is just another area where Massachusetts can grow in being a leader.”

DiDomenico said he is hopeful about the coalition’s chances this year because of Healey’s commitments to inclusive sex education, his conversations with House co-filers Rep. Jim O’Day of West Boylston and Rep. Vanna Howard of Lowell, as well as recent state action taken to shore up access to medication abortion imperiled by recent Supreme Court rulings.

House Speaker Ron Mariano is “going through the details and having conversations with members,” a spokesperson said. Mariano stood outside the State House with other elected leaders and reproductive health organizations to express support for moves to protect access to medication abortion earlier this year.

Senate leadership has been enthusiastically on board with the act for years. Senate President Karen Spilka said in 2020, “There has never been a more important time to teach our youth about the benefits of having healthy relationships — and that begins with inclusive and accurate sex education. Sadly, we know all too well the consequences of unhealthy relationships, which is why it is so important we prepare our students so that they can make informed decisions.”

The Legislature’s joint Education Committee has not yet scheduled hearings for the House and Senate versions of the Healthy Youth Act or Decker’s bill.

This story was originally published at CommonWealth.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)