Mascareñaz: Denver Teachers Need More Money. But Not at the Cost of Educational Equity for the City’s Black and Latino Students

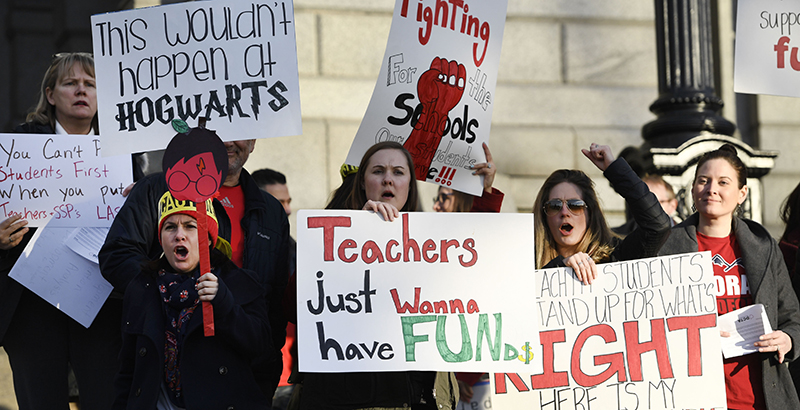

For the first time in 25 years, teachers in Denver are likely to strike on Monday, a teacher revolt that would have major implications for over a decade of education reinvention locally and around the country.

By striking a match with the kindling of the earliest modern Denver education reforms, activist teachers are gambling that public sympathy for their low pay will translate into other policy wins. The strike may tell us the public is aligned with teachers in Denver, as it has been in other cities across the country. An agreement could still emerge to paint a third way forward for other districts to emulate. It could also illuminate, once again, that Denver is simply different from other districts. But ultimately, the nation and our town will once again endure a sad drama pitting educators against educators for a smaller slice of the pie, while students pay the price.

When I taught first grade in a turnaround school nearly 14 years ago, my starting salary was barely above $30,000. I was lucky — teaching in rural New Mexico, my cost of living was very low. That is not Denver in 2019. Yet it became obvious early in my career what my teacher and principal mother had been telling me for years: Our society does not value educators with pay and stature. My sister, a nationally board-certified teacher who taught for almost a decade, left to find a central office job because as a single mom, she needed flexibility and couldn’t stay strapped to a teacher salary. I’ve seen it firsthand — not only do we not value educators as we should, we make it impossible for them to stay in the field.

In December, the Denver Public School board appointed Susana Cordova as superintendent. Her first task — a real baptism by fire — was to lead the negotiation with the Denver Classroom Teachers Association over the issue of ProComp. ProComp, approved by Denver voters in 2005, over time authorized $33 million in additional salary in exchange for incentives for performance and for teaching in high-needs schools. It was one of the first national examples of pay-for-performance and modernized professional incentives.

Cordova negotiated with the assumption there was a real deal to be had. The union, through a kabuki dance of strike threats and theatrical public negotiations, moved the district toward numerous union positions (compromising to enhance predictability, base pay, and credit units for advancement). Negotiations ended with the district offering to dedicate nearly $50 million more toward teacher salaries over the next three years. The proposal was an average of 10 percent increases, or a $6,000 raise for most teachers, with predictions that some educators will see raises of up to $20,000 (this includes one-time alignment bonuses some teachers will see). In contrast to recent negotiations in Los Angeles and Oakland, where proposed amounts were far less significant and the districts more recalcitrant, DPS showed enormous willingness to provide a better quality of life for teachers.

Indeed, from reading various proposals, DCTA got a significant amount of what it wanted — new paths for teacher increases, a clearer pay table, the largest proposed salary in decades, and a significant change in the performance pay structure. The final offer raised the starting teacher salary to the second-highest in the Denver metro area. Cordova even aligned with union rhetoric, stating she agrees that “right-sizing” the central office through dramatic cuts (likely the elimination of 100-plus jobs) is a priority.

The union has argued that the district’s numbers aren’t real, but if we can’t read proposals as honest, then we can’t compare proposals at all. Also, the union’s claim that more money is available for salaries than the district is offering is an unanchored reductionist argument — of course there is, but when does that end? With English Language Services cut? Special ed services cut? While certainly all parties agree that reductions are needed, one wonders if the union won’t be satisfied until the last position at the central office is gone.

Nationally, the teacher movement is pressing ahead with renewed energy and a clear agenda. After the Supreme Court’s Janus decision last year, the #RedForEd movement has rightly captivated our national dialogue around unfair working conditions and pay for teachers. Educators deserve more, and I have yet to see anyone at the negotiating table say differently. Teachers deserve far more than what most districts are willing or able to pay.

Yet unions are not confining their policy objectives to salary tables and living wages. They are pushing to eliminate or mitigate performance pay and incentives, and could soon advocate for retracting mutual consent (which ensured that our struggling schools did not get saddled with the lowest-performing teachers). In L.A., the union also extracted a promise for the district to recommend a charter school moratorium to the state. So we cannot pretend the issue is only teacher pay and respect. We must see it for what it is: a renewed offensive for higher ground in a larger debate on public education policy.

There are legitimate complaints about the way much of the educator-related politics, practice, and policies of Denver this past decade have come about. I came to understand many of the educator frustrations while I was working in the DPS central office. Teacher evaluations and other requirements may have represented major shifts in the field, but they seemed overburdened with rubrics, frameworks, point scales, and impenetrable bureaucracy. Teachers were not in charge of their own profession, and now they are telling us that this is no longer acceptable. I believe they are right.

Ironically, they are channeling more than a decade of mistrust and frustration at the first educator superintendent in years willing to give them a dramatic raise. The union has many real complaints about the system, but it needs to also answer for why, over the past 25 years, it has voted to strike only under female superintendents of color, letting white male leaders off the hook for the consequences of a strike. The union’s majority-white membership deciding to strike has direct consequences for our majority-black and -brown student population. These facts are not reassuring to the diverse families or community leaders of Denver.

I think it is now clear that likely no deal out there would stop the union from striking. And why not? Events across the country have shown that the national and local media are sympathetic (and, in many cases, rightly so), and unions have been able to extract large concessions. If DPS has already given so much, why wouldn’t the union get more from an actual strike? DCTA not only wants the win and credit for the pay raise, it wants the optics of the strike nationalized, and it wants to mobilize its base for the November school board elections, where many of the policy objectives they seek will be up for consideration.

The union could still overplay its hand. If Denver voters resent that their lives are being disrupted by folks who aren’t willing to take a 10 percent pay increase, the strikers will likely find little sympathy among people who haven’t seen a pay increase that large in years. Community leaders of color are questioning the larger race and achievement issues at play in the discussion (and, very telling, union leaders didn’t show up to an event on this topic hosted by the Colorado Black Roundtable). In a startling reveal of the union’s valuing equality over equity, it wants significantly lower incentives for teachers who work in high-needs schools. A letter from civil rights and community groups has now called for the district and the union to retain incentives for teachers in low-income schools. Finally, and most consequentially, parents of students whose lives and learning are disrupted may find the strike untenable.

Coalition Statement Protect Teacher Incentive Pay (Text)

The standoff is further dividing our already broken field of education. Leaders of schools are reporting major disagreements and painful conversations within their buildings. Teachers are pitted against teachers, families against families. It does seem likely that a significant number of Denver teachers will get paid more next year, and that will really make a positive difference for most families and educators. But this will come on the back of more than 100 passionate civil servants, many of them lifelong educators themselves, losing their jobs. For them and their families, that will be a major and tragic event. We have designed a system where in order to give our educators a raise, others who spend their days supporting schools must lose their livelihood. Sadly, in our city and society, there is no solidarity among these two groups who are committed to education.

It may yet again be the case that Denver is simply a different place than all the other cities that have gone through this challenge. We have voted to give teachers a raise in exchange for accountability, and we may end up asking voters again to weigh in. Our superintendent may realize that her fellow educators are with her and find a way out. Or maybe the high-flying Denver success story is finally coming back down to earth, beset by larger forces beyond our city and now entangled, for better or for worse, in a national whirl of change.

Landon Mascareñaz is senior partner for advocacy and alliances for the education advocacy group A+ Colorado. Prior to that, he was executive director of strategy development and family empowerment for Denver Public Schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)