Macedonia: How Florida Private Schools Are Using Assessments and Data to Make Great Academic Gains for Low-Income Students

Student assessments are viewed as a necessity for educational accountability — and an anxiety-provoking experience for students, teachers, and parents. Unfortunately, assessments are often misunderstood and frequently ignored.

However, in Florida, a quiet transformation in thinking about assessments is spreading in the most unlikely arena: the private school sector. Not in the large, elite schools; rather, it’s happening in small, often religious-based schools that are within reach of low-income students thanks to the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, which provides low-income students with financial assistance to choose a private school that might be a better fit academically than a traditional public school. At these schools, tuition is minimal, families often qualify for free or reduced-priced lunch, and students tend to be among the lowest-performing in their prior public school, regardless of its performance.

The result has been more schools using data to drive instruction like they’ve never done before — and more students making academic progress.

In 2016, Step Up for Students — which last year awarded tax-credit scholarships to 98,810 economically disadvantaged Florida students — entered into a partnership with the Northwest Evaluation Association, founder of the Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) Growth assessments, to bring evaluations, professional learning, and ongoing support to schools serving Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students.

Administered three times a year to 8 million students nationwide, the MAP Growth assessment provides teachers and administrators with detailed information on students’ academic growth and achievement compared with national norms. There is an individualized Student Profile Report that includes not only assessment scores but also guidelines for targeted instruction that educators and parents can implement. Teachers receive detailed reports that sort students into learning groups based on their scores. These assist the classroom teacher in determining which students should work together for small-group instruction, remediation, or enrichment.

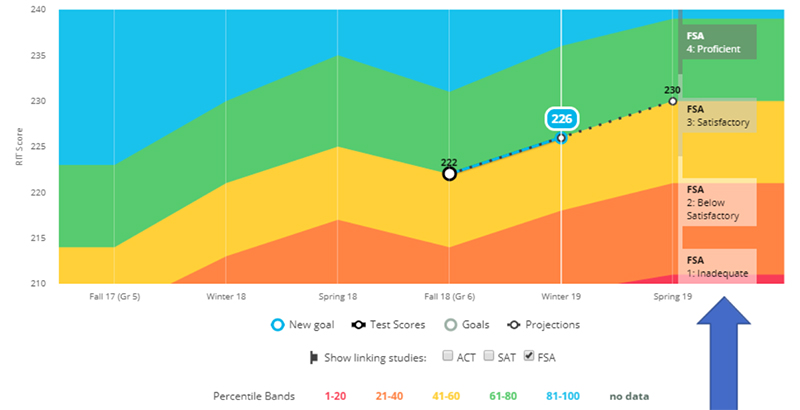

In addition, MAP Growth data can be converted to the Florida Standards Assessments, which the state uses to measure education gains in public schools, thus allowing a true apples-to-apples comparison between public and private school students.

The Florida partnership engaged with 39 forward-thinking schools that volunteered to participate in a pilot study using the MAP Growth assessments, receiving a fee discount, free professional development from Step Up staffers, and ongoing personalized support for school staff. In 2017, another 200 schools signed up with the partnership, and for the 2018-19 school year, the number has grown to almost 400 schools.

Because the fall MAP Growth assessment is designed to identify where students actually are academically, the data often reveal that the grade-level curriculum that teachers are prepared to teach is not necessarily what their students are ready to learn. For our Florida teachers and administrators, this was a bleak realization. These educators understood that if they continued doing what they had always done, they would get the same dismal results.

What was needed was to change instruction and curriculum. Schoolwide data maps were created to chart where all students’ scores fell, regardless of grade level, in math, reading, language arts, and science. So, for example, all students receiving a score of 200 were ready to learn the same content, regardless of what grade they were in. Teachers and administrators began rethinking grade-level instruction, and the commonly accepted belief that the third-grade curriculum worked for all third-graders began to crumble.

Reports drawn from the data provided teachers with specific goals for each student, becoming a critical tool for guiding instruction, and helped teachers group students across grade levels for instruction based on what they were ready to learn, not what grade they were in. Team members researched best practices and resources, and they focused on looking at students at instructional — not grade — level.

Schools found more targeted instructional time for all students, whether they were at, below, or above their grade levels.

The winter assessment revealed individual student data on both growth and achievement, enabling teachers to determine whether students who were low achievers had shown significant growth, just as they could see whether their high achievers were showing little or no growth.

The data allowed the teachers to make midyear adjustments to student groupings, instructional practice, and interventions. Administrators began holding weekly team meetings with teachers using the test data to discuss progress and challenges and to share ideas.

The schools used data from the spring assessment to evaluate their students’ annual growth. While the association reports that around 55 percent of MAP students nationwide made their projected growth in 2017-18, for the nearly 20,000 students in the 192 pilot program schools, 67 percent achieved their projected annual growth in math and 66 percent made growth in reading. The vast majority of those students had begun the school year below grade level and in the past had struggled to make learning gains in reading and math.

A key to success was teachers and administrators committing additional time to understanding the reports — and having the courage to change their traditional teaching practices to meet the needs of all students. They did this voluntarily, without it being imposed on them.

Most importantly, they used the assessment for instruction — to teach their students what they were ready to learn.

Carol Macedonia, Ph.D., is vice president of Step Up for Students, overseeing the Office of Student Learning. She spent over 30 years in public school education as a teacher, principal, director of professional development, assistant superintendent, and university adjunct professor.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)