Lowery: Giftedness Doesn’t Discriminate by Skin Color or Income Level — and Gifted Education Programs Shouldn’t Either

“We have a powerful potential in our youth, and we must have the courage to change old ideas and practices so that we may direct their power toward good ends.” —Mary McLeod Bethune

When I was a teacher, I taught gifted and Advanced Placement classes in a school where the hallways were filled with students from all racial and ethnic backgrounds. However, in my classroom, I often found myself to be the only person of color.

Later, I became a principal, and the first time I toured my new school, I knew where the advanced and AP courses were, because all those students were white — in a school that was otherwise not. These all-white classes had become so common that somehow, to many adults in the building, it seemed normal. Inevitable, even.

I was determined to change that, so we started doing open access to AP courses and ensuring that we were creating pathways to high-level coursework, not barriers to it. Changing that required us to open our eyes and take a good, hard, clear look at who was getting opportunities to take on rich academic challenges and who wasn’t.

Decades later, things haven’t changed much across America.

Both then and now, it’s not that white students are somehow more gifted or intelligent or harder-working than their black and Latino peers. It’s that students of color aren’t being identified early — and as often — for accelerated programs and enrichment, or that their parents might not know about AP courses or gifted and talented programs or how to fight to get them in. These children simply aren’t being given the chance.

In a recent report, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute highlighted disparities in access to gifted programs in our schools. This report, and the Civil Rights Data Collection statistics on which it is based, further confirmed what decades of data have made clear: America’s public schools continue to underestimate — and underserve — students of color and low-income students.

Children in low-poverty schools are more than twice as likely to participate in gifted programs as their peers in high-poverty schools. And across high-, medium-, and even low-poverty schools, students of color are drastically underrepresented in such programs.

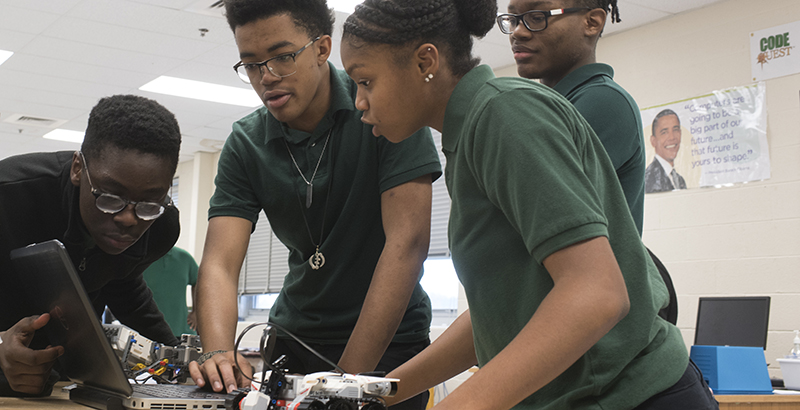

Part of the issue, as the Fordham paper indicated, is that students of color and those from low-income families are less likely to attend schools that even offer academically rich programs like gifted and talented. And it’s not just gifted programs that are missing: CRDC data also reveal that schools serving high percentages of African-American and Latino students are less likely to offer high-level lab sciences like chemistry and physics — classes required for entry into many universities and that serve as gateways into growing STEM fields.

But even when students of color and students from low-income families do attend schools that offer gifted programs and high-level coursework, they are still less likely to be placed in those classes. In fact, according to the data in the report, racial disparities in access to gifted programs are actually higher in low-poverty schools. Black students make up 4.8 percent of students in those schools but only 2.6 percent of students enrolled in gifted programs, while Latino students make up 11.2 percent of total enrollment and 7 percent of students in gifted programs.

Disparities like these are visible across grades — and across the board — when it comes to access to academically rich offerings:

● African-American and low-income students are underrepresented in high school Advanced Placement courses.

● In states that have a college prep curriculum, like Massachusetts and California, low-income students are often less likely to complete those course sequences.

Even when we look exclusively at high-achieving students, gross disparities persist:

● African-American students who were high-achieving in math in fifth grade are nearly half as likely to be placed in algebra in eighth grade as similarly high-achieving white students.

● High-achieving students from low-income families are less likely than their similarly prepared high-income peers to be placed in advanced math courses, advanced science courses, and AP/International Baccalaureate courses.

Eliminating these persistent — and pernicious — inequities will require real changes both in policy and in practice.

I know from my time as a principal, and later as state chief in Maryland and Delaware, that there are education leaders who are hungry to right these patterns of inequity and are making real progress. But decades of experience tell us that many won’t. That’s why it’s so critical for states to send a clear signal to schools that such disparities in opportunity are unacceptable. One key way states can do that is by putting in place accountability systems under the Every Student Succeeds Act that hold schools responsible for improving opportunity and outcomes not just on average, but for all groups of students, at every level of achievement. Right now, too many states fall short in this respect.

Ultimately, however, turning these inequitable patterns around will require school and district leaders to change the way they “do school” — to examine their data, take a good, hard look at adult beliefs and biases, and identify ways to expand access to rigorous learning opportunities for students who have been denied them for far too long.

America’s public schools are filled with untold, powerful potential. But as long as we accept rich educational opportunity being doled out unevenly, as long as we lack the courage to change old ideas and practices that bar too many students from high-level learning, we will continue to see unequal ends. And we will continue to squander the powerful potential of too many truly gifted students of color and students from low-income families — not because they couldn’t handle the challenge, but because we never gave them the opportunity to even try.

Lillian M. Lowery, Ph.D., is The Education Trust’s vice president for preK-12 policy, research, and practice, focusing national attention on inequities in public education and actions necessary to close opportunity gaps and raise achievement.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)