Losing a ‘Godsend to the Bronx’: Parents Push Back Against DOE Shakeup

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

To most New York City residents, it may have seemed like a boring, bureaucratic change.

In early March, Schools Chancellor David Banks announced he would eliminate the executive superintendent role from the Department of Education’s internal structure and require district superintendents to re-apply for their jobs. The shifts received a quick mention in The New York Times story covering the chancellor’s remarks, his first major address as head of the DOE.

But to Bronx parent Ilka Rios, the news hit like a thunderbolt.

“Initially, when [the chancellor] made the announcement, at that point, I didn’t hear nothing else that came out of his mouth,” she said.

To her, the update meant only one thing: Her borough, which suffers the city’s highest poverty rates and lowest high school graduation rates, would lose a leader who had finally started to turn around the area’s schools, Erika Tobia.

“Dr. Tobia has been a godsend to the Bronx,” Rios told The 74. “Every time the Bronx finds someone to help them get better, it’s like someone from downtown swoops in and removes them.”

A 30-year education veteran in the borough, Tobia had only assumed her post as executive superintendent 11 months prior. The position itself was created just three years earlier in 2018 under former Chancellor Richard Carranza, who added the roles to increase oversight and support for district superintendents.

With a total of eight positions, one or two per borough, eliminating the posts will save millions of dollars, said Chancellor Banks, who founded a Bronx high school early in his career.

“We want to push those dollars closer to schools,” the chancellor later said. “That’s all this is about.”

The idea that parents would rally to preserve an additional layer of bureaucracy is hardly typical and, indeed, not all parents are equally enamored with their executive superintendent. In Brooklyn, Yuli Hsu praised the chancellor’s move.

“When the previous chancellor added the executive level of superintendents, to me it just added another level of expense and bureaucracy,” she told The 74. “I haven’t really noticed any impactful change since [Executive Superintendent Karen Watts] arrived” in her role in North Brooklyn.

The 74 reached out directly to each of the city’s eight executive superintendents. None responded.

In the Bronx, Tobia’s parent-first style won families over.

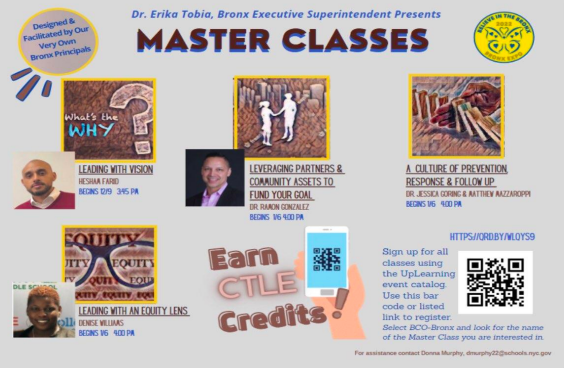

The leader ran food drives, held sessions to build trust between campus police and families and launched a series of “Master Classes” for adult education that regularly drew dozens of participants. Every month, Tobia held gatherings — dubbed “just us” meetings because she honored parents’ request that no other district officials attend — for families to share their education concerns, said Rios, who was president of the Community Education Council in the borough’s District 12 for nearly a decade.

“For us in the Bronx, it’s really important because we never had that voice before,” said Farah Despeignes, District 8’s CEC president. “That is why parents are so upset… that they would eliminate that position.”

With parents and school leaders across the city looking to get a handle on the new administration’s education agenda, they say how the chancellor moves forward with his planned shakeup will be an early test of his priorities and willingness to incorporate community voices.

So far, Rios remains unsatisfied.

“The chancellor nor the mayor, neither one of them brought us to the table to ask us parent leaders how it was working with [Tobia],” she said. “They just made the decision, ‘We’re eliminating the position.’ And I get it, eliminate the position, but then tell us, you’re going to put her somewhere else in the district.”

Despeignes penned a December letter on behalf of her parent organization, NYC Coalition for Educating Families Together, to then Mayor-elect Eric Adams urging him to consider the Bronx executive superintendent for a post where she could engage with and uplift families across the city.

Banks has dropped indicators that he may still heed their advice. While the executive superintendent role will be going away at the end of this school year, some of those leaders “may reappear in other positions” in the DOE, he said.

During a state legislative hearing two days after the chancellor’s announcement, Bronx Assemblywoman Chantel Jackson pressed Banks on his choice to get rid of the position prized by many of her constituents.

The chancellor empathized: “I’ve heard from a lot of parents in the Bronx who are really supportive of the Executive Superintendent Tobia,” he said. “I’ve become very fond of her myself in the two months that I’ve been here and I’ve seen her work — so stay tuned.”

“We are working diligently to finalize the execution of [the chancellor’s] announcement and additional details are forthcoming,” a DOE spokesperson wrote in a March 14 email to The 74.

The Power of Community! When we come together…we can achieve anything! @Csd7Bx @CECD8Bronx @CSD9Bronx @CSD10Bronx @CEC11NYC @District12CEC @TeamCintronNV @BXHS_SuptPeart @SuptCook @bronxbp @DOEChancellor @WorldVision pic.twitter.com/yUChZZuflC

— Erika Tobia (@BxSuptTobia) February 2, 2022

Experts agreed with Banks’s stance that, structurally, the role “adds a level of bureaucracy without adding enough value to schools and students.” According to David Bloomfield, the extra layer actually restricts the authority of local leaders.

“The executive superintendents handcuffed the superintendents, and now the superintendents will be freer,” said the Brooklyn College and CUNY Graduate Center education professor.

“This is a win-win,” he added. Because there will now be 46 superintendents — presumably some of them new faces after the reapplication process — reporting to the chancellor rather than eight executive superintendents, “the chancellor’s office is going to have more information to assess its policies and the principals and superintendents will be able to act with more discretion.”

Since taking office in January, Banks has repeatedly vowed to improve the city’s schools “from the bottom up” by giving principals more autonomy, an agenda item reminiscent of the Bloomberg era.

Parent leaders like Kaliris Salas-Ramirez, of Harlem, say their schools became more responsive to the community once the executive superintendent role was introduced.

“There was a systemic issue in my district where parents were not empowered and parents didn’t have a voice,” Salas-Ramirez told The 74. “When the executive superintendents were put in place, Marisol [Rosales, the Manhattan leader at the time,] was incredibly responsive to parents on the ground.”

That indicates, said Andrea Gabor, author of After the Education Wars, not that another layer of bureaucracy was necessary, but that perhaps Salas-Ramirez’s district superintendents weren’t properly doing their job.

“In an ideal world, teachers and principals should be the ones who are responsive to parents,” the Baruch College professor told The 74. “You should not have to go through a four-layer cake in order to get some kind of a response.”

The DOE took a similar stance: “[School] leaders will be successful when they work closely with families. … There are phenomenal schools in every neighborhood across the city, and it is our responsibility to cut bureaucracy and grow what is working at the school-level,” said Press Secretary Nathaniel Styer.

Still, based on her experience in the Bronx, Despeignes pushed back.

“Yes, it is another layer of bureaucracy… but it’s a layer of bureaucracy that is needed because it brings all the schools and all the superintendents under one tent,” she said.

“It’s not outlandish,” noted Bloomfield, to eliminate executive superintendents in most boroughs, but keep them on a case-by-case basis in areas where they’re making a positive impact, perhaps like the Bronx.

Back in Brooklyn, District 14 Community Education Council President Tajh Sutton said the bulk of the Adams’s administration’s work building families’ trust is still to come.

“I’m happy to see one layer of the bureaucracy go, but what does that look like in practice? And how does it improve the lives and interactions between families and districts on the ground?” she wonders. “Are we talking to the most marginalized members of each district community to really try to get a sense of, ‘Is this superintendent effective? Is this principal effective?’”

Hsu, also on the District 14 CEC, agrees. She’s been frustrated by the lack of action after she raised concerns over anti-Asian racism her kids and others have experienced in school, she said. To her, re-ordering the DOE’s organizational chart is not enough.

“You’re just kind of shuffling pieces of a broken system around,” she said. “What I really want to hear is about meaningful change from the ground up and meaningful engagement with parents.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)