Los Angeles Schools Reopens All Libraries — But Forgets About the Books

But according to the latest district estimates, the majority of students across Los Angeles will still be forced to rely on under-stocked library collections filled with outdated materials.

District numbers show that the average age of a book in a LAUSD library is now more than 20 years old, and that the books-per-student ratio is a shocking 35 percent below the state average.

Even more dire: Most district schools have only a minimal budget to spend on bridging this gap—if they have any additional library funds at all.

“The libraries are still woefully inadequate, and some librarians are loath to take some off the shelves because they will remain empty,” said Franny Parrish, the political action chairwoman for the California School Employees Association, the union that represents library aides. “We have actually come across books with titles like ‘One Day We Will Put a Man on the Moon’ and that’s absurd. You can’t give obsolete information out, it’s a disservice to the students.”

Some school libraries were closed well before the 2008 cuts — stretching back 10 or even 15 years — and some principals decided to completely close the school libraries rather than depend on parent volunteers to run them, since they may mix up books and cause more confusion. Also, some libraries are staffed through funding by PTAs, and books are replenished by book fairs or school fundraisers, meaning that school libraries in more affluent areas now bear little resemblance to those in poorer neighborhood.

“It’s wrong to be pimping out our children by having them sell candy to raise money for books or to pay for a library aide,” Parrish said. “It’s offensive. A library should be a necessity for every school.”

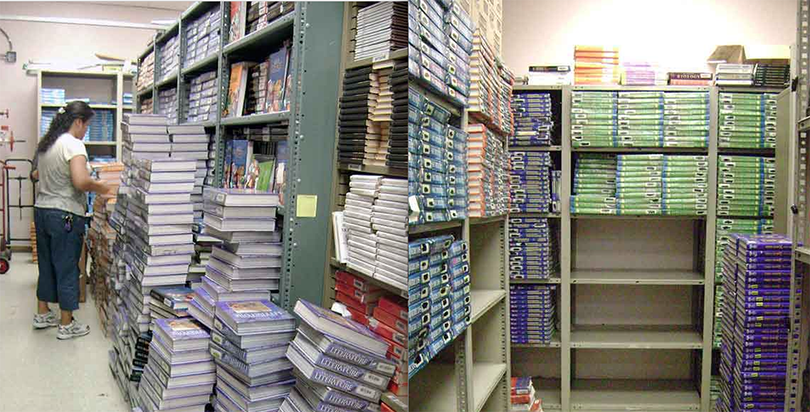

Concerned about the decline of school libraries, school board member Monica Ratliff initiated a Modern Library Task Force that issued a report in June 2014 that suggested three years of strategies for the district to try to reach the California school library standard of 28 books per student. At the time, LA Unified had only 17.6 books per student.

Today, district numbers show, that number has only increased 1.1 percent to 17.8 books per student.

“It is good news that we have the renewed staffing because libraries were literally shuttered, and that was not appropriate,” Ratliff told the LA School Report. “The bad news is the book collection is out of date and too thin.”

Ratliff said the district must figure out how to update the books and find donors willing to help. All the books now at the district are worth an estimated $205 million.

“I’m sure there are book lovers out there who would want to help purchase books for our kids,” said Ratliff, whose staff looked into an update of the libraries a few weeks ago. “I interacted with some Library Aides and I appreciate that they do try to buy books of interest to students and that are Common Core-related. We just need more resources.”

The second-largest school district in the country has not had a major influx of books for its libraries since some state funding between 1999 and 2002, according to district officials. In 2011, as part of a civil rights settlement with the federal government, LA Unified had to pay for Library Aides at 80 schools with significant African-American student populations. Library Aides are usually hired for elementary schools and Teacher Librarians hired at middle and high schools can also teach classes.

“We cannot depend on parents to buy books for the libraries, it will just create more disparities in different parts of the district,” Ratliff said. “And we still need to improve staffing.”

The Teacher Librarian-to-student ratio at LA Unified is one Teacher Librarian for every 5,784 students, which is far below the national average of one for every 1,026 students. (The recommended ratio by Modern School Library Standards is one for every 785 students).

Under Superintendent John Deasy, librarians and aides were considered unnecessary and cut during the recession, but his successor Ramon Cortines vowed to reopen all of the libraries starting with high schools. Now, Superintendent Michelle King has renewed efforts to get libraries opened at all the schools again by rehiring staff, but it’s a far cry from the more than 800 Library Aides once working at the district.

Elementary schools with smaller libraries (10,000 books or fewer) usually hire Library Aides, and this year, the district has 356 of them, with 184 paired to support two school sites. Of those, 133 are assigned six hours a day at a single site and 39 are assigned three-hours at a single site, according to district spokesperson Monica Carazo. Only three Library Aide positions are vacant and are expected to be filled before the beginning of school, Carazo said.

Of 85 middle school libraries, 38 have full-time positions funded while four have part-time positions. Other positions are paid with discretionary money from the school funding, sometimes with help from PTA groups.

Of the 84 high school libraries, including span schools from 4th to 12th grades, 74 have full time Teacher Librarians who also teach classes, and 10 schools have part-time positions.

The district built 130 new schools in the past 15 years and so those book collections are newer, and the district is emphasizing their use of a “weeding” process to cull older books.

But after books are weeded, there’s often no money to buy replacements.

The budget for new books last year for Tiffany Federico at Walter Reed Middle School in Studio City was $1,800 — about $1 per student. That’s how much they raised at the Scholastic Book Fair, selling books to students and parents, with a percentage going back to the school to buy books for a classic library with high ceilings built as part of the FDR Work Progress program in 1938.

“My goal this summer was to research some grants and figure out how to do the Donors Choose and make inroads into the community with the parents to make the library survives this year,” Federico said. “I got rid of a lot of books, many of them hadn’t been checked out for decades, and I have no budget for more books.”

Another issue for Reed, and a big secret, is that the book detection bars at the doors of the library haven’t worked for at least two years. The scanners are supposed to sound off if an unchecked book passes through it.

“We keep them up because it still serves as a deterrent and the kids think it still works, but it will cost about $13,000 to replace it, and that’s unlikely to happen,” Federico said.

Lost or stolen books are yet another problem. Books cost about $25 each to replace, not including the cost of processing and filing them.

“Millions of books are missing because the libraries have been closed for so long,” said Parrish, who works at Dixie Canyon Community Charter School in Sherman Oaks. “If I were to tell you that at one school there was $75,000 worth of computers missing, people would flip out, but if it’s $75,000 worth of books missing from the library no one really addresses that.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)