Lessons Learned on the Road From North Carolina’s Cooperative Innovative High Schools

Research continues to affirm the positive effects of CIHS on students, who consistently outperform traditional high schoolers

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Last fall, EdNC visited all 58 community colleges over the span of four months. We called the campaign Impact58, as it was an opportunity for us to learn more about the impact of our state’s community colleges.

We spoke to faculty, staff, and students about some of the issues that will be at the forefront of this year’s legislative session, including dual enrollment opportunities such as Cooperative Innovative High Schools (CIHS).

Given the research showing the many benefits of CIHS and recent legislative changes to the funding model for these schools, we took the opportunity to visit as many CIHS as we could to witness their impact firsthand. Here’s what we learned.

What are Cooperative Innovative High Schools?

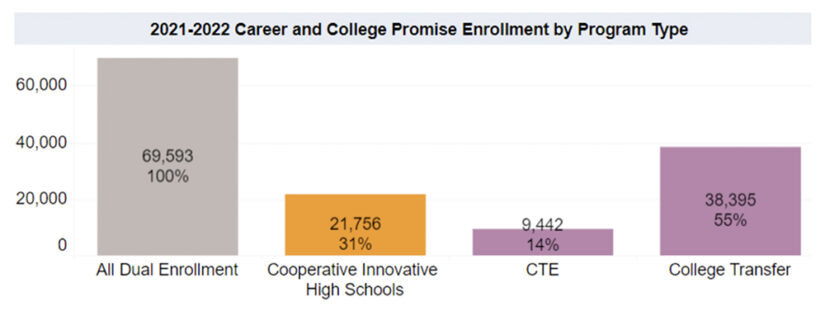

CIHS are one of the three dual enrollment programs offered under Career and College Promise (CCP), which is a partnership between the N.C. Department of Public Instruction (DPI), the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS), the UNC system, and North Carolina’s independent colleges and universities. CIHS students account for 31% of those enrolled across the three CCP programs in the state.

During our Impact58 visits, we learned about the role community colleges play in CCP as a whole. Read more here.

CIHS include early colleges, middle colleges, and STEM and career academies, which are all united under a common goal: to provide students with the opportunity to gain tuition-free college credits, including an associate degree or industry-recognized credential, while in high school.

These schools are committed to making sure they are reaching a wide variety of students, particularly those that may otherwise lack the opportunity or ability to attend college. In traditional dual enrollment programs, research has shown that student participation over-represents white students from affluent, college-going backgrounds. In order to address that equity gap, North Carolina’s legislation establishing CIHS states that schools must target one of the following three student populations:

- First-generation college students.

- High school students who are at risk of dropping out.

- High school students who would benefit from accelerated instruction.

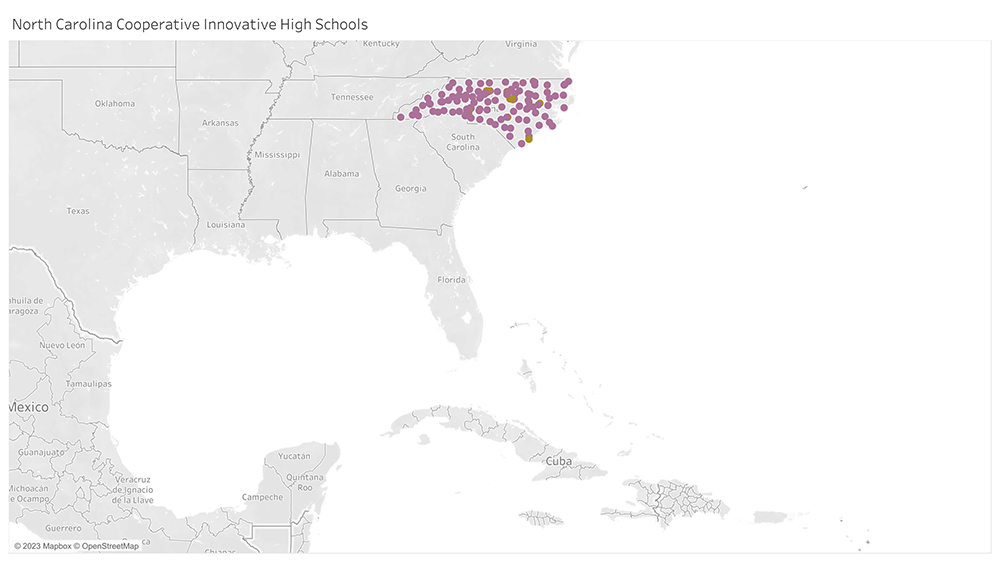

Below is an interactive map displaying all 134 CIHS programs operating in the state during the 2022-23 school year, differentiated by those partnering with community colleges and those partnering with the UNC system or other independent colleges and universities.

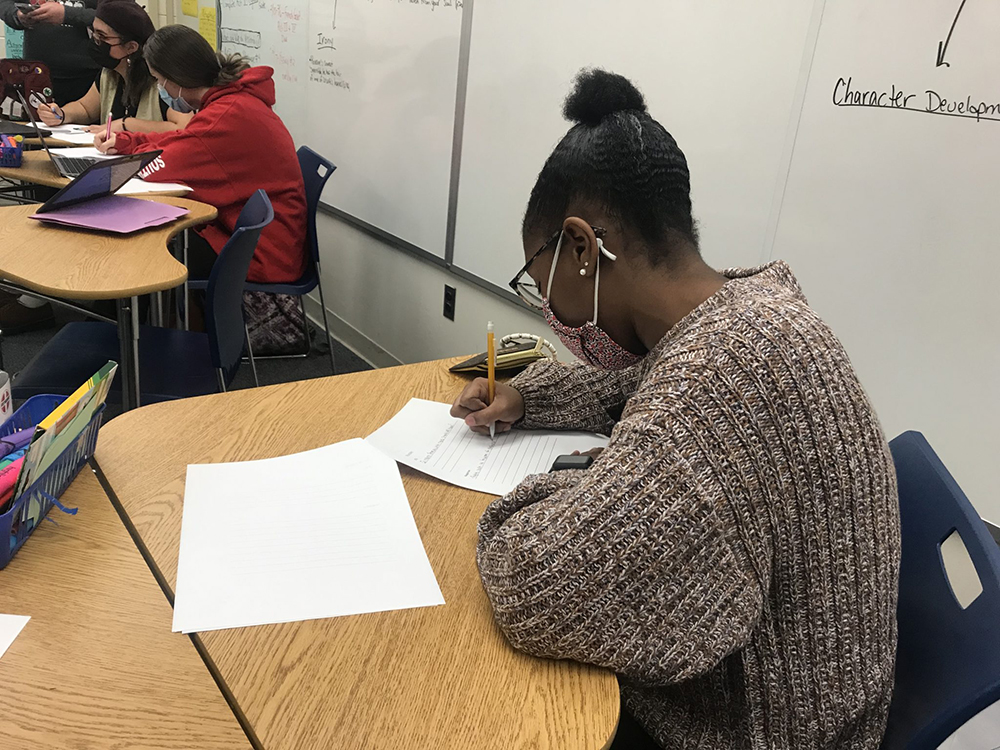

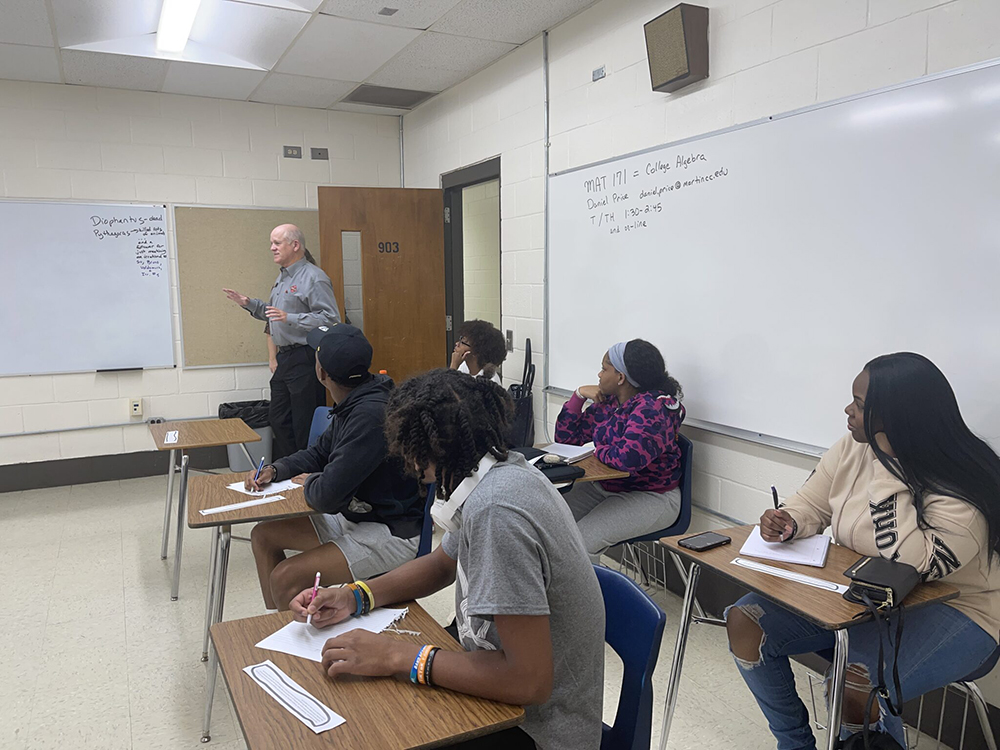

Part of what adds to the unique high school experience for these students is their size and location. These schools are required to have no more than 100 students per grade level to ensure an intimate learning environment, and they are often located on the campus of their partnering institution of higher education. Students not only experience college in their coursework but in their day-to-day lives on campus as they interact with professors and other college students.

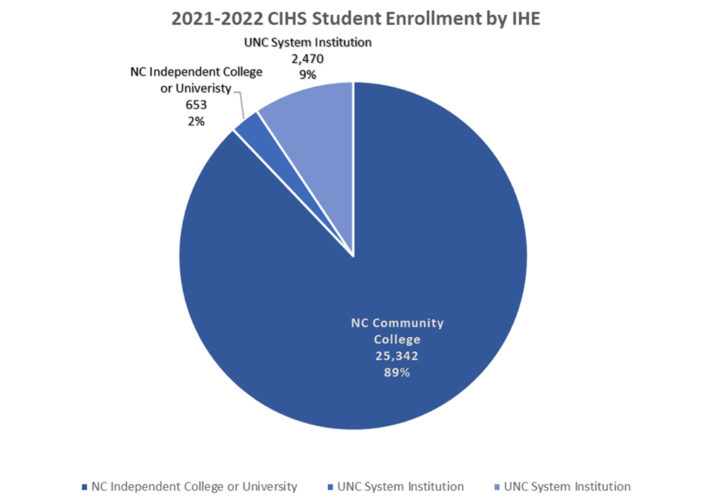

Of all students enrolled in a CIHS in the 2021-22 school year, 89% attended schools that partner with a community college.

Below are some frequently asked questions about CIHS, updated in fall 2022.

Student success by the numbers

Research has consistently shown that CIHS students outperform traditional high school students on a variety of metrics. This Q&A by EdNC highlights ongoing research by Julie Edmunds, Fatih Unlu, Elizabeth J. Glennie, and Nina Arshavsky, which has tracked the performance of N.C. early college students for 17 years and has found overwhelmingly positive results.

A recent draft report to the General Assembly offers the following data points from the 2021-22 school year as verification of the success of the CIHS model:

- “High school retention and completion rates for CIHS were above the state averages, with the average CIHS rates above 95%.

- The average high school drop-out rate of CIHS programs was below the state average.

- CIHS students at community colleges received better grades, on average, than the general population of students, with 84% averaging a passing grade of a C or better. This is 13% higher than the general population.

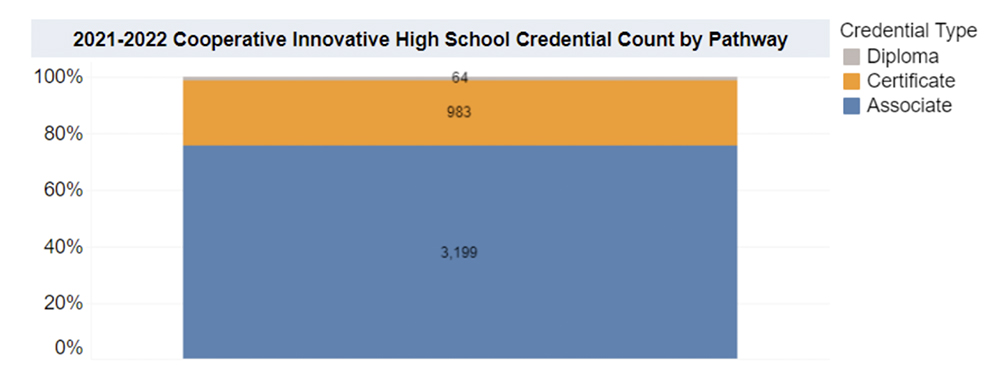

- CIHS students also earned a total of 1,047 diploma and certificate credentials, based on NCCCS data. This represents a total of 2,231 individual credentials earned from both agencies, an increase of 515 credentials from the previous school year.

- 3,199 CIHS students graduated with an associate degree. This is an increase of 282 students from the previous school year.”

In addition, during the 2021-22 school year, 62% of CIHS (83 out of 134 schools) received a school performance grade of A, 26% received a B, and 7% received a C. In comparison, just 4.8% of all N.C. public schools received a school performance grade of A, 16.1% received a B, and 33.3% received a C in 2021-22.

What sets the CIHS model apart?

From our Impact58 visits, we gained insight into the importance of a strong partnership between the college and the district, the factors that contribute to student success, and how changes in funding have and could continue to hamper the implementation of this schooling model.

Stories from teachers and students overwhelmingly attributed the success of the CIHS model to the schools’ design and implementation. DPI has a set of guidelines that standardize the practice for establishing and running a CIHS. This ensures that as new CIHS crop up across the state, they are following the foundational principles of existing schools that have proven to contribute to student success.

The design elements deemed essential to the implementation of a CIHS in North Carolina include:

- Preparing graduates for college, careers, and life.

- Collaborative partnerships between the community and the partnering college.

- Innovative instructional practices in the classroom.

- Personalized student supports.

- Leadership and professionalism of staff.

- Innovative design and operations of CIHS.

See the CIHS Design and Implementation Guide by DPI below. The document also highlights best practices from CIHS across the state.

These CIHS design guidelines are facilitated by an intimate learning environment and small student population, a rarity at traditional public high schools. This intimacy allows students to form meaningful relationships with their teachers and peers, making the school feel more like a family.

Natasha Snyder, the Pender Early College High School (PECHS) college liaison, described the depth of teacher-student relationships, saying, “We know our students well enough that we can tell by their facial expression if they’re having a bad day when they get off the bus.”

That level of intuition is crucial to providing solid wraparound supports for students. It allows students to feel comfortable asking for help when they need it, and it offers teachers insight into which students may be falling behind before it is too late. It certainly contributes to how CIHS students are able to outperform students in traditional high schools despite being in a more challenging learning environment.

If you are part of a local education agency (LEA) and are interested in creating a CIHS in partnership with an institution of higher education, see this application information from DPI.

Partnership is key

Collaboration between a CIHS and its partnering institution of higher education is key to ensuring that students have access to the resources and support they need as both a high school and college student. It is through this partnership that schools are able to blend a high school and college curriculum, coordinate instructors for college courses, and provide access to college facilities and resources, among other things.

One aspect that helps these partnerships succeed is a memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the local school system and the partnering community college. The MOU sets a precedent for proper communication and assigns specific responsibilities to each entity, which are reviewed and revised annually. This ensures that both the school system and the community college are on the same page about how to best serve their shared CIHS students.

The fact that CIHS are often located on their partnering college’s campus also facilitates collaborative efforts between the two. Staff at each institution are able to build relationships and work together to ensure students are on track to earning college credits, an associate degree, or a technical credential. On the college campus, staff do not differentiate between high school students and other college students. CIHS students are given equal treatment and equal resources.

Schools not located on the community college’s campus reported having a more difficult time integrating their students to the college community and ensuring they feel like real college students. These students often have less opportunities to take their college courses in person at the college and instead remain on their CIHS campus throughout the day and take their college courses online. While these students may still be offered the opportunity to utilize college facilities and resources to aid their studies, those who lack transportation to the college campus are less likely to be able to do so, although many schools find a way to offer transportation.

To ensure distance does not impede upon collaboration, schools not on their partner college’s campus reported relying heavily on their community college liaison to manage the partnership between their school and the college. The community college liaison serves as the go-between for the CIHS and the community college, acting as the point person for managing the partnership between the two and scheduling CIHS students’ college courses each semester.

Snyder explained, “I feel like it doesn’t feel like work for two different institutions. We are here together for students. … We arrange everything so that we are fully knowledgeable on both sides so that we can better serve the students and meet their needs.”

The ability to overcome all of the logistical challenges involved in maintaining this partnership is integral to the success of this model of schooling. And it is clear from what we heard in our travels that there is no shortage of success within North Carolina’s CIHS programs.

A range of experiences

CIHS provide students with invaluable opportunities upon graduating high school that they may not have otherwise had. Many are focused on ensuring students complete their associate degree and successfully transfer to a four-year college or university. Others are focused on preparing students for a range of post-graduation experiences, such as entering the military or the workforce.

We learned from our time on the road that it is not uncommon for community colleges to partner with multiple CIHS that offer different experiences for students. This often happens when there is a need in the local community that can be filled by opening another CIHS to address the gap.

For example, Wilson Community College partners with two CIHS to serve Wilson County students: Wilson Early College Academy (WECA) and Wilson Academy of Applied Technology (WAAT). While WECA focuses on ensuring students graduate with an associate degree and can transfer to a four-year school, WAAT focuses on preparing students for entry into the fields of biotechnology, information technology, automative systems technology, criminal justice technology, or applied engineering technology.

“(WAAT) came about from some conversations with our workforce development committees across the county about the need for a workforce pipeline,” said principal David Lyndon. “Our county commissioners and our school system and our community college all came together to design something so that we could have a pipeline that put our students into work in our county, so it strengthened our county overall.”

We heard a similar story a few hours southeast where Cape Fear Community College partners with four CIHS, including one, Southeast Area Technical High School (SEA-TECH), that opened in 2017 with four career academies.

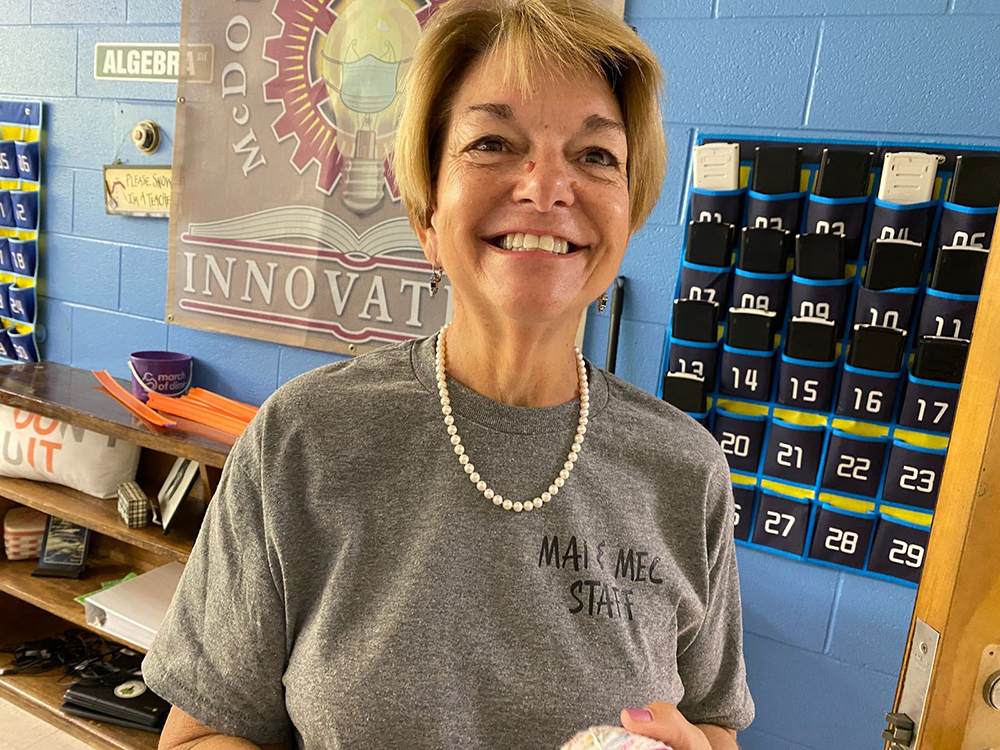

McDowell Technical Community College is home to two early colleges that co-exist peacefully side-by-side, even sharing faculty, classroom space, and other resources. The McDowell Academy for Innovation (MAI) moved to the campus in 2021, and Billy Cline is the principal. The McDowell Early College (MEC) has been on campus since it started in 2006, and Lisa Robinson is the principal.

At Jackson County Early College (JCEC), the majority of students get an associate of arts or science transfer degree in four years and go on to attend UNC system universities. The degree “waives their liberal studies so they are able to jump right into their career studies as soon as they go to university,” said Principal Melanie Jacobs.

Some early colleges are housed in trailers. The Edgecombe Early College High School is located on Edgecombe Community College’s campus in a building that once served as a correctional facility. Other early colleges, like the Wake Early College of Information and Biotechnologies and Henderson County Early College and Career Academy, are in new, state-of-the-art buildings that look and feel like a college. A brand new early college is under construction in the Cherokee County Schools.

‘I’m trying to set an example’

From our time on the road, we heard plenty of reasons why students chose to attend a CIHS and the effect it had on their lives. Students often cited their parent’s wishes, the desire for a challenging workload, or the motivation to get a head start on their postsecondary education as reasons for opting into the CIHS model.

Makayla, a current 12th grader, said of her decision to attend Pender Early College High School:

“I have eight younger siblings between my mother and my father… And neither one of my parents went to college. And so I’m trying to set an example for my siblings … and (show) them that you can do whatever you put your minds to.”

The draft report to the General Assembly shares moving stories about students in CIHS programs across the state as indicators of the impact of this model of schooling. Here is one that encompasses how CIHS programs circumvent barriers to postsecondary access and the value that has for our state’s future workforce:

“Due to time, motivation, and costs, I might not have pursued a two-year degree beyond high school on my own. Early College East has offered me an opportunity of a lifetime and has changed my future. I will graduate with a skill set to enter the job market and have a career with a competitive salary. For this I will always be grateful for the opportunities provided to me while a student at Early College East.”

Isaiah, a student at Challenger Early College, told EdNC’s Emily Thomas:

“I see myself with the group of people I’ve met here…I feel like the bond I created at this school is the most caring bond I’ve ever had with people in my life. … And in 10, 20, 30 years down the road, I think because of this school, (A) I’ll be doing the thing that I want to do most in my life and (B) I’ll be doing it beside the people I’ve met here.”

For all of these students, and many others like them, their early college experiences granted them both the courage and the opportunity to chase after their dreams.

CIHS legislation over time

CIHS programs have been the subject of a slew of legislative changes in the past decade.

Among those changes was a 2017 Senate bill that reorganized these schools’ funding structure. In the past, CIHS programs were able to apply for and receive additional funding totaling $300,000 per year. The 2017 legislation made it such that funding is based on a school’s economic tier, wherein Tier 1 county schools receive an additional $275,000 annually, Tier 2 schools receive $200,000, and Tier 3 schools receive $180,000. The result was effectively a funding cut for all CIHS.

A 2019 House bill attempted to restrict CIHS funding by only providing additional funding to schools in their first three years. Though the bill passed both the House and Senate, it was vetoed by Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper.

A 2020 Senate bill legislated that the State Board of Education may only approve additional funding for three new CIHS programs each year. This significantly limited the rate of expansion across the state for this model of schooling.

Why funding matters

During our time on the road this fall, we asked school administrators about the effects of these legislative changes. We heard about how changes to funding affected salary allotment for staff members, including the integral college liaison position. After the shift to tier-based funding, schools scrambled to find other sources of funds for those salaries, and some schools mentioned having to cut positions altogether.

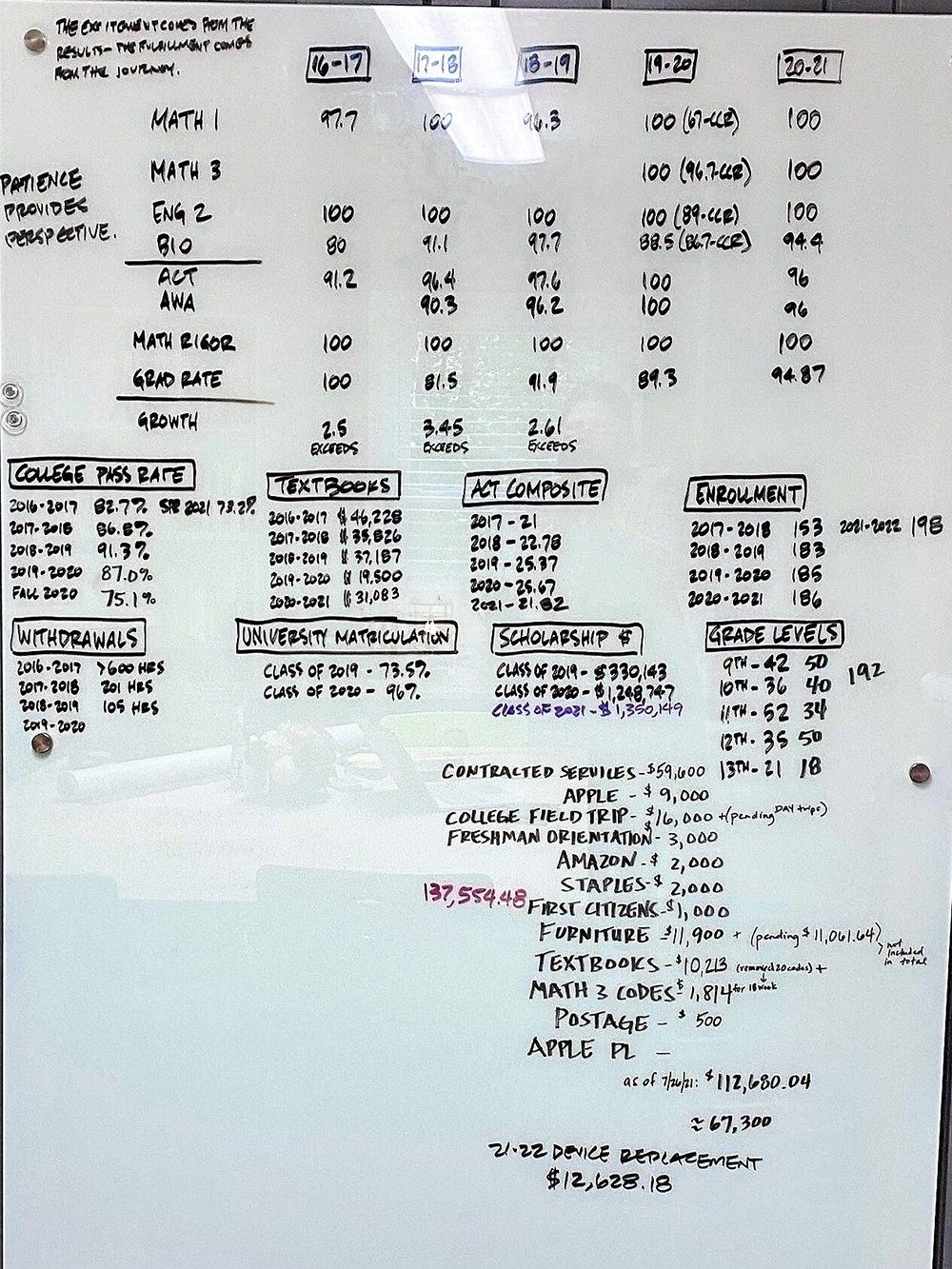

Many schools pointed to the cost of college textbooks as a major pain point. College courses require up-to-date textbooks, which can be pricey, and it is important that CIHS students do not have to bear those costs. But, with less funding, schools have found it increasingly difficult to pay these costs themselves.

The photo below depicts how Lori Fox, the principal at Haywood Early College, has reduced the money she spends on textbooks to create money for college field trips.

Some of these funding shortages were partially offset by the federal funds given to schools to counter the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Staff were grateful that in spite of overall funding cuts, their schools had these supplemental funds. But, as schools begin to wean off of these federal dollars, financial concerns arise yet again.

North Carolina as a national leader

It’s clear from both existing research and from the stories we heard on the road that the CIHS model benefits communities as a whole by providing underserved students with educational opportunities they may have otherwise lacked and preparing them for the workforce.

North Carolina is a national leader in the CIHS model, boasting a high number of CIHS that stretch across the state, steady enrollment numbers, continued expansion of the model, and a community college system that is eager to partner with local school districts to maximize educational opportunities for students.

Part of what makes North Carolina’s CIHS model an ideal blueprint is the buy in from the many different agencies and institutions involved — not to mention the commitment of CIHS staff and students, which we witnessed firsthand on our trips across the state. It is those very individuals who comprise the success of this model of schooling.

This article first appeared on EducationNC and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)