Lesson from Oscar-Nominated Film ‘The Holdovers’: Hollywood Hates Tough Teachers

Pondiscio: If you're an educator who loves your subject and holds your students to high standards, then you’re a movie villain.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Warning: This article contains spoilers for the Oscar-nominated movie “The Holdovers.”

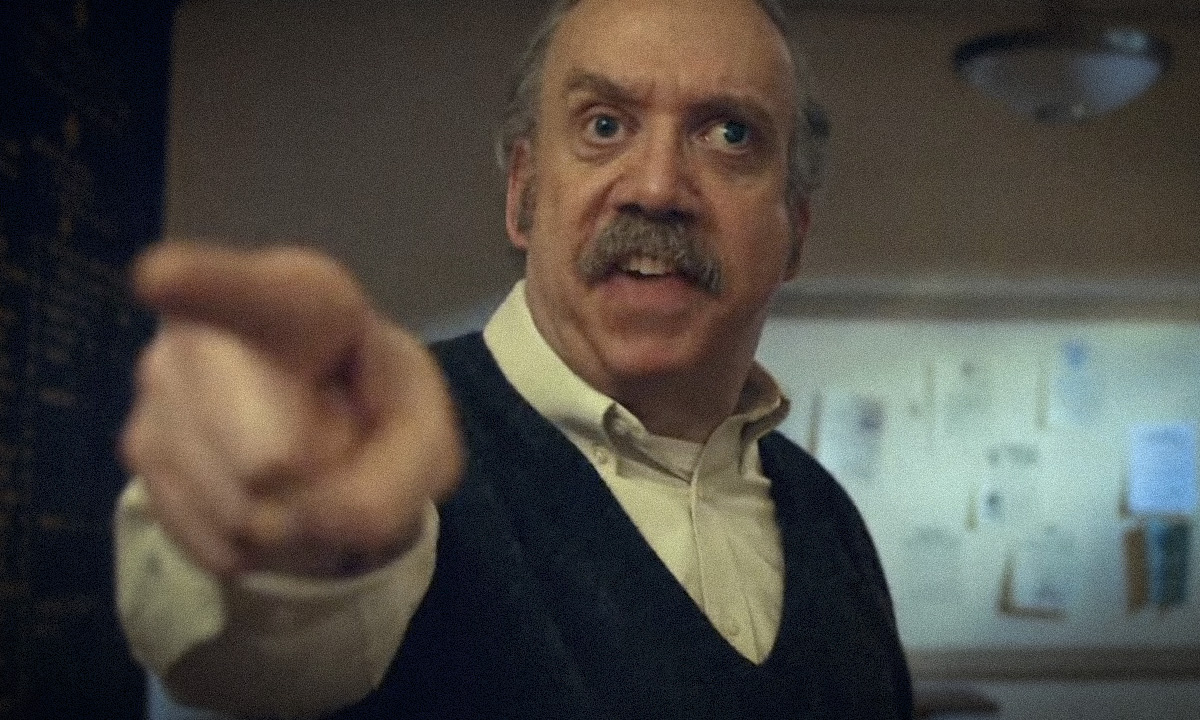

Paul Giamatti is among the most talented actors of his generation. He has a particular gift for portraying loners, losers and oddballs like cartoonist Harvey Pekar in American Splendor and an angst-ridden wine snob in 2004’s Sideways. His distinctive, drooping everyman face is marked by expressive eyes and a receding hairline that radiate world-weary disappointment.

He was born to play a teacher.

Wait. What!? But Hollywood loves teachers, you’re thinking. Yes, but only a certain type of teacher: mavericks and rule-breakers who are allied with students against authority, conformity, structure and the system, man! Think Dead Poets Society, Freedom Writers, School of Rock, Mr. Holland’s Opus. Hollywood’s hero teachers are invariably iconoclasts who barely teach at all. They inspire students, unlocking the hidden natural talents that schools keep tightly bottled up.

Standards? Rigor? Hard work and high expectations? Box office poison. Teachers who love their subject and make demands of their students are at best figures of fun in the movies. At worst, they are tyrants.

The Holdovers is up for five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay. Giamatti earned a Best Actor nomination for his portrayal of teacher Paul Hunham, a figure of scorn and derision at Barton, a New England boys’ boarding school. Hunham is a pitiful loner, acerbic and anachronistic, with no friends or close colleagues. He teaches (naturally) ancient civilizations. His students hate him, and one senses he’s kept on staff only out of a sense of obligation by the headmaster, one of his former students. Hunham is the only character who talks unironically about the qualities the school is trying to instill in “the Barton Man.” He refuses to pass a failing student who is the son of a senator and a school benefactor. “We cannot sacrifice our integrity on the altar of their entitlement,” he sniffs at the headmaster. “I’m just trying to instill basic academic discipline. That’s my job. Isn’t it yours?”

Ordinarily, this refusal to pay obeisance to power and privilege would be portrayed sympathetically, even heroically. But The Holdovers is the latest in a long line of movies to thumb its nose at tradition, character and high standards. Driving home the point, the headmaster calls Hunham “hidebound” to his face. Even the setting — boarding school! single-sex education! 1970! — unsubtly telegraphs the anachronism of the entire model of education. The movie takes place over Christmas break; the title refers to students unable to go home for the holiday, of whom Giamatti’s character is given reluctant charge. Five holdovers are quickly winnowed to one, a defiant and rebellious kid (another teacher-movie archetype) named Angus Tully.

The last performer to be nominated for Best Actor playing a teacher was Robin Williams for Dead Poets Society (1989), which shaped the maverick teacher trope (and convinced a generation of credulous Teach For America corps members that the key to engaging indifferent students is standing on your desk). Poetry teacher John Keating orders his students to tear pages from their textbooks and encourages them to think for themselves and live their best lives. Convention dictates that where there is a hero teacher there must also be an antagonist. Keating’s is the school headmaster, a former English teacher and (naturally) a strict traditionalist who opposes his methods. The school’s four pillars — tradition, honor, discipline and excellence — are invoked not as worthy ends or aspirations, but as a straitjacket. Carpe diem, y’all.

The list of movie teachers and administrators who are authoritarians, tyrants, martinets or simply tintype foils to maverick educators and their free-spirited students would fill volumes, stretching back to John Houseman’s Oscar-winning turn as a demanding law school professor in The Paper Chase (1973). There’s Dolores Umbridge in the Harry Potter series, Miss Trunchbull in Roald Dahl’s Matilda, Ferris Bueller’s high school principal Ed Rooney and the assistant principal who torments the detention-serving students of The Breakfast Club. If The Holdovers breaks new ground, it’s in making such a teacher the central role, not a supporting figure of derision.

Here’s how much Hollywood believes and rewards the tyrant teacher archetype: The last actor to take home an Oscar playing a teacher was J.K. Simmons, who won Best Supporting Actor for 2014’s Whiplash portraying a music teacher so demanding that he literally drives students to madness and suicide. Giamatti’s Holdovers character, Hunham, is no less inflexible, seeming to take perverse delight in failing students. Tellingly, he becomes a sympathetic character only when he takes Tully to Boston in violation of school rules, and in front of the kid tells bald-face lies about his life and career to a former classmate at Harvard, where we learn he was expelled over a plagiarism accusation. So, you see, it’s all a sham: the high standards, academic discipline, personal integrity, “Barton men never lie.” Teacher and student (naturally) are now free to form a close personal bond for the remainder of the film.

Schools in the movies are invariably oppressive places that limit students’ potential and deny their gifts. The one notable exception to the rule that tough teachers must be villains, Stand and Deliver (1988), paints a picture of a high school where math teacher Jaime Escalante, played by Edward James Olmos in another Oscar-nominated role, is viewed with suspicion by other faculty members. AP calculus? Those kids?!

There is a consistent exception to the Hollywood rule that good teachers must be rebels and rule-breakers. Show me a sympathetic portrayal of a tough teacher who pushes kids relentlessly and accepts nothing but their best efforts, and I’ll show you … a coach. In Hoosiers (1986), a high school basketball coach played by Gene Hackman is a strict taskmaster. He drills his team hard and forbids them from shooting baskets during practices, to work instead on passing, defense and stamina. In their first game, he orders his teams to make four passes before shooting, and benches his star player who disobeys. Even after another player fouls out, he continues the game with just four men, to ensure the lesson sticks. Better to lose the game than to lower one’s standards. Later, when the town tries to fire the coach, that same selfish-but-talented player, who has come to see the light, saves his job. Note the contrast: The headstrong kid adopts the coach’s methods and mindset, not the other way around. Ditto The Karate Kid (1984), Remember the Titans (2000), Miracle (2004) and Coach Carter (2005).

The Hollywood rule is good coaches push kids to greatness while good teachers inspire them, but never the other way around: The sports movie has never been made — and likely never will be — in which the school wins a state championship after the coach calls off practice and stops being a hardass. But in the classroom, it’s just the opposite. Hollywood coaches win by holding their charges to the highest possible standards and expectations. Classroom teachers win over audiences only when they drop theirs.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)