Learning Pods’ Lessons For Schools About Supporting Effective Teacher-Student Relationships

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When schools closed down last spring, some parents and educators responded by forming “pandemic pods,” or small groups of students who came together outside of school to learn during the pandemic.

These experiments from last year provide some important examples of how families and educators can affirm students’ identities, instill a sense of belonging, and help them resolve conflicts and navigate social situations when they are freed from traditional assumptions and rules about how school is supposed to look.

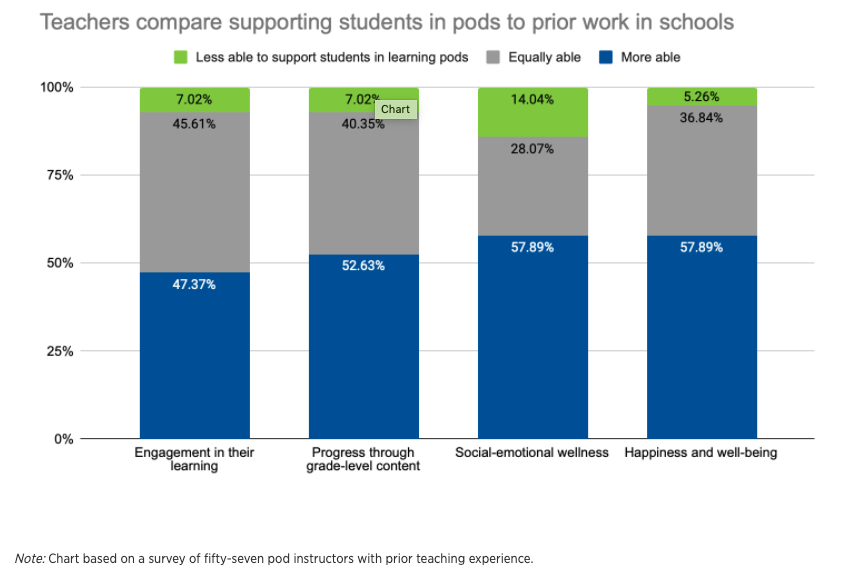

Over the past year, we surveyed 253 pod parents and educators throughout the United States. Among the 101 teachers we surveyed, 57 percent previously taught in a public, charter, or private school. We also conducted detailed interviews with twenty-seven parents and thirty-five pod educators to gain a deeper understanding of how they supported students’ well-being.

Fifty-eight percent of surveyed teachers reported they were better able to support their students’ social and emotional well-being in pods than they had been in traditional classrooms.

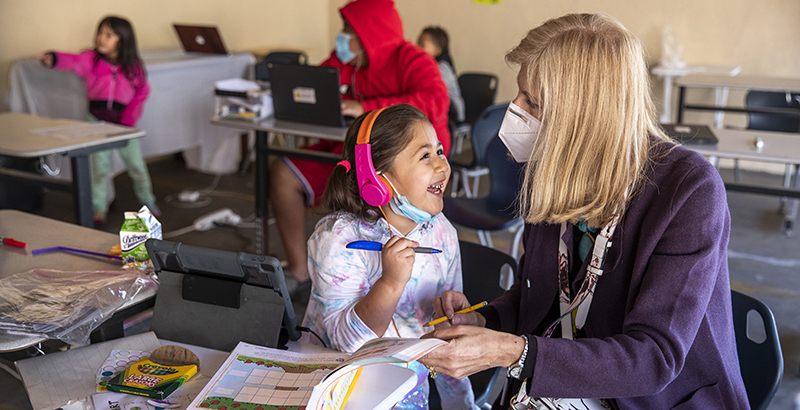

In interviews, parents and teachers said the combination of small group sizes and flexibility to shape the learning experience enabled educators to form strong relationships with their students and ensure students felt seen, known, and heard, which, in turn, helped them support students’ learning and well-being.

Learning in pods “really shifted to focus on the social and emotional, and working together as a group,” said one teacher. “[Learning is] more focused and more based on their interests, and [with a] more reactive and smaller group, I can do more than a teacher who has thirty students.”

Pod teachers said they had more control over their schedule and lessons, which allowed them to address students’ needs on the fly. When teachers could be more responsive, they said their students trusted them more, which improved relationships throughout the pod, leading to a more positive learning environment.

For example, one teacher we interviewed described how she used her flexibility to work closely with a second-grade student who struggled with interpersonal skills and socializing with his peers. The structure of the pod allowed her to spend additional time to understand his frustrations and help him communicate his needs. This led to stronger relationships between students. “He learned to be with other children … We were able to deal with so many social and emotional issues over time in such a communicative way,” she said. “We had so much time in between lessons.”

Ultimately, pod environments allowed teachers and students to build deeper connections with each other and work through conflicts that arose— something that might be difficult to achieve in large, traditional classrooms where it’s easier for students to get lost in the crowd.

One parent said the pod experience was “tremendous for [my child’s] social and emotional development … They had conflict. They had disagreements. They had a hard time working things out sometimes. But they learned to … sit down and talk and hear each other … They were like, ‘These are my people. I’ve got to figure this out.’”

Another parent remarked that her six-year-old daughter had developed better communication skills than most adults while attending her pod. The strong relationships that formed in pods helped set up an environment where teachers could easily support students as they worked through social situations and learned to advocate for themselves, creating a learning environment where students felt safe among their peers.

Small groups and teacher flexibility are hardly new or innovative ideas. But pandemic pods are a good reminder of their power. Both are difficult to implement in traditional school systems with large classes, mandates, and pressures on teachers.

Still, school system leaders can draw lessons from small pandemic learning communities to better support their students’ well-being and learning. For example:

—Community-based organizations and parents spend the most time with students outside of school and understand their needs best. They know how to create environments where students feel safe, known, and heard. Leaders should honor their expertise by forming partnerships with organizations and parents (e.g., including them as advisors) to design new learning environments—both inside and outside traditional campuses—where students feel valued and motivated to learn, as some districts have done with learning hubs.

—Within schools, students often form their most authentic relationships and experience some of their most profound learning outside of their core classes, on what some scholars call “the periphery”(link is external) of school (extracurricular activities, or elective classes like music or drama). Schools should look for ways to develop that same intimacy and authenticity in math, English, or science classes.

—While existing tools for gauging student well-being are often inadequate, measuring students’ perceptions of safety and belonging at school can help leaders understand and respond to their needs. Myriad surveys can measure student well-being; leaders should be intentional about using survey data as a starting point to dig deeper into their needs and experiences. For example, one charter management organization used a combination of student surveys and interviews. When leaders learned students didn’t feel understood by teachers, they searched for ways to improve teacher-student relationships and create a culture of belonging. Creating a feedback loop where leaders track and respond to students’ needs can help build trust and show students that their school cares about them.

Fundamentally, the positive experiences many families and teachers had during their unplanned experiments with learning pods underscore the benefits of giving educators and families the ability to shape learning environments around students’ needs—rather than assumptions about what the school day should look like or how students should spend their time.

This flexibility allowed teachers to respond more effectively to student needs, which in turn built trust, strengthened relationships, and created the conditions for better learning. The question this raises for our education system is: What will it take to give educators, parents, and students everywhere that same power over their learning environment that allows student needs to drive every decision?

Lisa Chu is a research analyst with the Center on Reinventing Public Education. This analysis originally appeared at CRPE’s education blog, The Lens.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)