Langhorne: These 5 D.C. Charter Schools All Have the Same Mission but Couldn’t Be More Different

By Emily Langhorne | May 13, 2019

Washington, D.C.

During the year I student–taught in Washington, D.C., I was fortunate enough to observe and teach at multiple public schools, both district and charter. The two charters schools where I spent many hours were vastly different from one another.

Washington Latin Public Charter School had a diverse-by-design student body, a classics-based curriculum and a Socratic approach to teaching. SEED Public Charter High School, on the other hand, was a college-preparatory, residential school located in one of the District’s poorest neighborhoods. It served a student body that was 98 percent African-American and over 60 percent economically disadvantaged, utilizing a holistic learning model that customized academic, social and emotional mental health services for each pupil.

Despite their differences, both schools were high-performing, and, unlike the district-operated schools where I student-taught, the educators running these schools had the autonomy to design unique learning models and create school cultures that met the specific needs and interests of their students.

Since then, I’ve been fascinated by the extraordinary amount of innovative school models — STEM, project-based, dual-language immersion, Montessori, etc. — in the District’s charter sector, which enrolls nearly 50 percent of the city’s public school students. This diversity of school designs, combined with D.C.’s universal enrollment system, has created a variety of educational options so that each student can find a best-fit school.

For this series, I decided to visit schools that were strikingly different from one another and used their unique qualities to do great things for kids. Like many of the public charter schools in Washington, D.C., these five “schools of the future” all provide a high-quality education, but the curriculum, teaching style, and school climate vary greatly from school to school. Center City Public Charter Schools Petworth campus has remained intentionally small since its conversion from a Catholic school. Moreover, it has continue to serve students from the community and adapt its service to meet the changing needs of the neighborhood as more English language learners moved to the area.

Inspired Teaching Demonstration School, a diverse-by-design school, serves students from across the District and emphasizes student thinking and creativity with its project-based curriculum. Serving a majority low-income population, Thurgood Marshall Academy (TMA) is the District’s only public high school without a feeder pattern or entrance exam. Prepared to take all kids regardless of their academic level, TMA has a law-themed curriculum, high academic standards and impressive college acceptance rates. Currently in its first year, Digital Pioneers Academy has implemented a “coding for everyone” learning model by integrating computer science class as part of its core curriculum. Lastly, Ingenuity Prep, intentionally located in the area of the District that needs the most additional seats in high-quality schools, uses computer-based learning and co-teaching to maximize the amount of time students spending learning in small groups.

Each of the schools offers a different type of school experience for D.C.’s public school students. And when students land in the right school, they can flourish in surprising ways. Here are their stories.

Center City Petworth: Inside One of America’s First Catholic-to-Charter School Conversions — ‘Intentionally Small,’ Built Around Character & Thriving

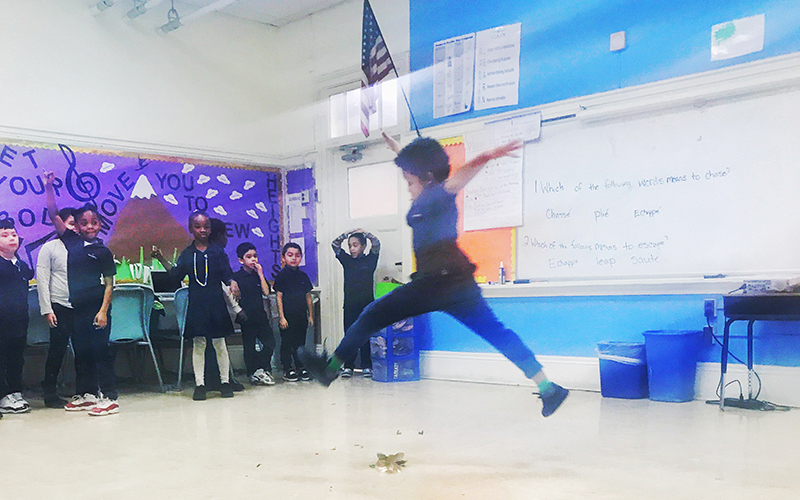

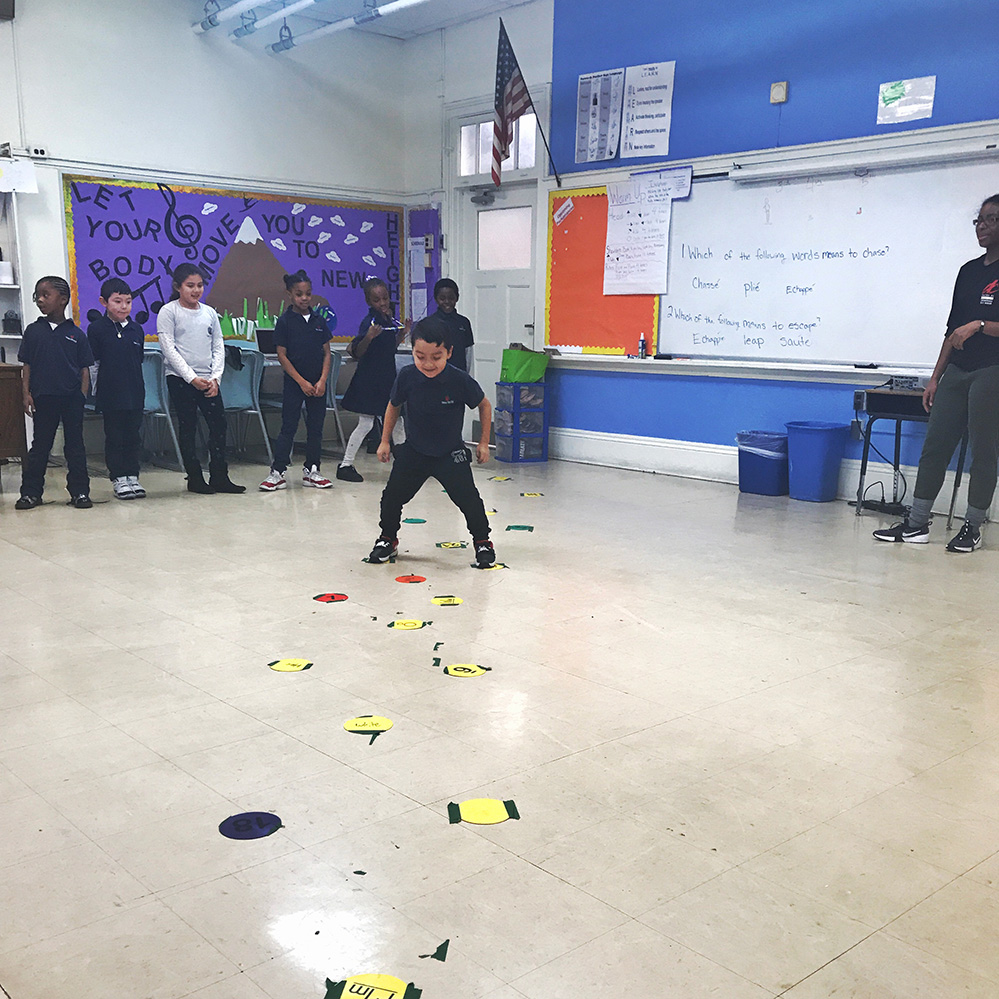

Three rows of second-graders stand facing the front of the classroom. A speaker emits sounds. First, a door creaking. Then, footsteps thudding and a wolf howling, all followed by the unmistakable opening riff of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

The students put their hands on their knees and take four big steps forward before swinging their arms quickly from side to side. When they’ve finished performing this simplified version of Jackson’s choreography, many fall to the floor, giggling.

Jordan Daugherty teaches dance at Center City Public Charter School’s Petworth campus. Today, her second-grade class is learning the difference between improv and choreography.

“That’s great,” Daugherty says. “Now face me upstage. That was choreography. Remember, improv is when you feel the music and move with it. Choreography is when you make up the moves in advance to match the song.”

At Center City Petworth, all students take dance year-round as a part of their regular schedule. It’s an enrichment course, along with STEM and physical education, all components of the school’s commitment to providing every student with a comprehensive education.

“We believe that we need to develop good citizens and well-rounded people, as well as scholars,” says Principal Nazo Burgy. “To do that, our students need to be socially and emotionally healthy. Play is really important to early childhood, and this is a place where kids can be kids. We have schedules, procedures, and routines, but our hallways are not silent.”

Center City Petworth is part of Center Public Charter Schools, a network of six intentionally small schools operating in four of D.C.’s eight wards. Each school has between 200 and 270 students in grades pre-K through eight and only one class of about 25 students per grade.

The Center City network began when a group of private Catholic schools, experiencing financial problems, was on the verge of being shuttered. Many of these schools, like Petworth, had occupied an important place in the community for nearly a century.

“Families wanted the school to survive,” says June Felix, a kindergarten teacher at Center City Petworth and the last remaining teacher from the school’s era as a Catholic institution. “Teachers and parents rallied behind it becoming a charter school.”

In 2008, as part of the first Catholic-to-charter school conversion in the country, the Petworth campus, along with five other Catholic schools, became Center City Public Charter Schools.

“It’s been a great change,” says Felix. “As a Catholic school, we could not take all students. Our community had started to change, and community members who wanted to come to our school couldn’t afford it. We didn’t have the funding to help students with special needs, either. As a charter, we can serve all of them.”

Today, Center City Petworth’s student population is approximately 45 percent Hispanic and 46 percent African-American, with 60 percent of students designated as economically disadvantaged. Currently, 25 percent of Petworth’s students are English language learners, a number that has been increasing each year.

“Our schools are like small neighborhood schools, so they mostly reflect our local community. Our size and the supply and demand of the school lottery, as well as the sibling preference, influences that,” says Alicia Passante, Center City’s ESL program manager. “At Petworth, almost all of our Spanish-speaking students’ families come from El Salvador. We also have a lot of families from Ethiopia and the Philippines.”

After the conversion, the schools’ new leadership removed all religious elements, but they decided to keep the schools small so that teachers could continue to emphasize character development and relationship-building, in addition to providing a high-quality educational program.

For the past three years, the D.C. Public Charter School Board has awarded Center City Petworth a Tier 1 ranking. Although the overall percentage of students scoring at or above proficiency on state exams is on par with the average score for all D.C. public schools, a larger percentage of the school’s “at-risk” and Black/African-American students achieve proficiency than the district-wide average, according to the Office of the State Superintendent of Education’s newly released school report card system. In addition, Center City Petworth boasts a higher in-seat attendance rate, a higher re-enrollment rate and a lower rate of chronic absenteeism than the district-wide averages.

Following the script — and not following the script

“Because of our size, teachers really get to know students,” says Hannah Groff, the schools’ language access coordinator. “They watch them grow up from kindergarten. Often, they know the family well before they even teach a student, and they often teach siblings.”

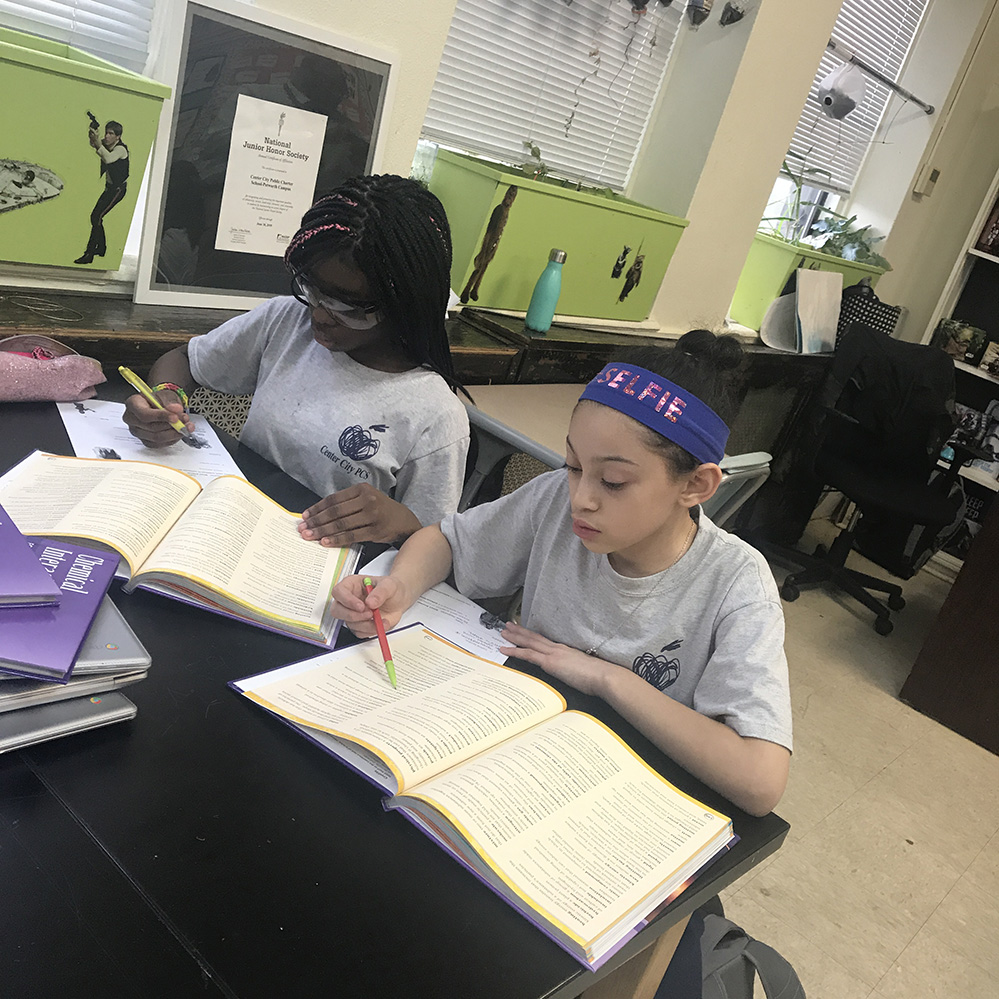

Center City Petworth prescribes Common Core-aligned curricula and materials for teachers, like Wit and Wisdom, a K-8 English Language Arts curriculum that emphasizes writing, language, speaking and listening standards by focusing each unit on an essential question and thematic text set, and Eureka Math, a pre-K–12 curriculum that stresses daily fluency lessons, conceptual learning and rigor. While the units and day-to-day lessons are provided, teacher creativity is still valued.

“We want teachers to follow the script and not follow the script,” says Passante. “For instance, Eureka Math was too advanced for many of our kids at first, so teachers had to find creative ways to scaffold it. And Wit and Wisdom is a very rich curriculum, but it needs hooks for student buy-in, and hooks come from teacher experience. They’ve got to make it their own by bringing their personalities into it.”

Because of the low teacher-student ratio, students receive a lot of individual attention. Pre-K to first grade is self-contained, taught by a lead teacher and instructional aid. In upper elementary school, teachers have looped classes — they teach the same students for two grades. From second through fifth, students take humanities with one teacher and math and science with another. In middle school, teachers teach all three grades, and there’s both a science and a math teacher. For all grades, the content area teacher usually co-teaches with an inclusion teacher, who specializes in English as a Second Language or special education, depending on the needs of the students in the class.

“There’s pros and cons to every teaching model,” Passante says. “The pro here is that teachers become masters in their content area, but it’s a lot of work because they prep for multiple grades. The big pro for our students is the building between grade levels. When a second-grade teacher also teaches third grade, that teacher knows exactly where the students need to be standards-wise at the end of second grade to be successful next year.”

Teachers also choose what electives the school offers. Middle school students take a different elective each quarter, usually choosing from three or four offerings. This quarter, some students are taking tap dance while others are taking robotics, where they use Lego Mindstorms kits to build and program their own robots. During the first day of the art elective, P.E. teacher “Coach Sam” Daniel taught students about the minimalist line drawings of Pablo Picasso before they created single-line drawings of their hands, in pen, so that they couldn’t erase. Teachers have to be informed about their elective subjects but not necessarily experts in the subject matter.

School leaders also encourage teachers to make time for their “passion projects.” Fifth-grade humanities teacher Shannon Nuzzelillo loves animals, so she partnered with the Washington Animal Rescue League to provide kids with volunteer opportunities. Her students have learned how to approach animals, and they’ve also practiced their reading skills by snuggling up with, and reading aloud to, a canine friend.

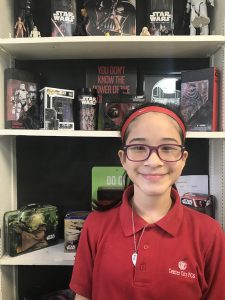

Middle school science teacher Mark Joyner’s classroom is decked out in Star Wars memorabilia. A bookcase behind his desk is filled with action figures. Stickers of C-3PO, R2-D2, Boba Fett and others cover bulletin boards. At the beginning of the year, he asks students to decide whether they want to join the Light Side or the Dark Side. Then the battle begins. Each day, they compete in “Science Wars”: trivia questions based on the week’s lessons. A drawing of lightsabers on the wall, with a scale ranging from Sith apprentice to Sith Lord and Youngling to Jedi Master, marks whether the Light Side or the Dark Side is the week’s winner. Joyner’s love for Star Wars is apparent throughout his classroom, except for the turtles. They are named after the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles; he let the students pick those.

Strengthening the small school community

“Being a small school is a blessing and a curse for students,” says Principal Burgy. “Everyone gets to know each other very well. The downside is you’ve got to learn to get along with your peers even if you don’t like someone very much. We focus a lot on social and emotional learning to help strengthen our community relationships.”

Each morning begins with a school-wide, student-led meeting. The students play games, talk about character and practice mindfulness. Each week, the meetings emphasize a different virtue that benefits the community, like patience, generosity and honesty. Every Friday, school leaders honor a student who demonstrates that week’s virtue.

Each grade also has monthly social-emotional lessons. Fourth-graders recently had a lesson on “thinking before speaking,” while fifth-graders focused on self-regulation and calming strategies, such as deep breathing, getting a drink of water and internal counting.

Because it can be challenging to have 3-year-olds and 13-year-olds in the same building, students participate in a “little buddies” program to promote cross-grade community. The older students partner with younger students as reading buddies, and together they read a book one month and then complete a project on it the next. At the end of the school year, they also work together on a school beautification project, such as painting the playground fence or creating a mural for the hallways.

“The ‘little buddy’ system helps us improve our social interactions with the younger ones,” says eighth-grader Chelsea Lazo. “It makes me happy. I like how we get to teach them and help out the community. It makes me think that when I grow up, I might like to do something where I help others.”

Her classmate, Nash Campo, agrees. “Even by reading with someone, I can build small relationships, and it helps me get to know my community better,” he says.

Staff members also conduct home visits to strengthen relationships with students and families. For the 2018-19 school year, the staff’s goal is to conduct a home visit to 90 percent of families. Lazo thinks that home visits are especially helpful when a new teacher or student comes into the community. “My mom felt relieved after the new teacher visited because she got to know her and felt better about sending my little brother into her class,” she says.

“Parent buy-in is the first big outcome. I can see that many parents feel more comfortable,” says Mike Bailey, a first-grade teacher and leader of the school’s family engagement program. “Once they see we have the best intentions for their children, they trust us. Once that trust is built, then we can work together to grow the child.”

Throughout the year, the school has many events — cultural heritage nights, family potluck dinners, a visit to a pumpkin patch, family breakfasts and more — that they encourage parents to attend.

“Parents become really trusting of this school because of the small community,” says Groff, the language access coordinator. “If they have issues, even when they aren’t school-related, this school is often the first place they come because they feel safe saying, ‘I need help.’”

“My parents, especially my mom, really like this school,” says Campo. He began attending Center City Petworth in second grade when his family moved to the U.S. from the Philippines. “It took a while for me to speak English, but my teachers were supportive. Over time, my parents got to know everyone at the school — all the teachers and staff — because everyone is really kind. In fourth grade, I had a mild stroke, and Ms. Burgy was really helpful. She took me to the hospital and explained everything to my mom, so she wouldn’t panic.”

The challenge of saying farewell

The transition from the small environment of Center City Petworth to a large-scale high school can be difficult, but the school’s staff works with students so that they’ll know what to expect.

“We really teach our kids how to be their advocates because we know that they’re used to this small school, and that high school could be a rude awakening for them. We hope that by teaching them to advocate for themselves from the start, they’ll understand how to use their voice to get what they need to be successful,” says Passante.

Eighth-grade students have a high school prep class each week with a counselor. The counselors work hard to assist students with getting into the best schools. They do research to match GPAs and test scores with selective and private school requirements to figure out which schools they’re eligible for. The students go on shadow visits to schools where they shadow other students, which helps them find schools where they’re a good fit. Each student applies to five schools through the class. Students participate in mock interviews with counselors. They write application essays and, for private schools, complete scholarship applications.

“It’s nerve-racking,” says Lazo, who hopes to attend either The School Without Walls or Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School next year. “All the applications and the essays, wondering if and where you’ll get in, but it’s also good because when you apply for high school, you’ll get used to how it feels and what to do when you apply for college.”

Counselors also work with families to help educate parents on why a convenient neighborhood school might not be the best option for their child. Many parents don’t like the idea of sending their son or daughter to a school outside the local community. Often counselors have to explain to parents why taking a bus for 40 minutes to a school across town will benefit their child in the long run.

“Our goal is to send 80 percent of our students to Tier 1 charter schools, private schools or highly selective DCPS schools. Last year, we were just shy of that, with 76 percent,” says Passante. “In general, we try to steer our kids away from the neighborhood high schools, but some do go there and are successful.”

Most students are excited about the prospect of starting high school, but they also realize that they’ve been fortunate to have such a homey environment during their early school years.

“Everyone here is a part of my second family,” says eighth-grader Ashley Velasquez, who has been attending Center City Petworth since kindergarten. “Everyone is so open, and the teachers are there whenever you need them.”

Campo agrees: “Years from now, I’ll still remember how we were like a family here.”

Inspired Teaching Demonstration School: A D.C. School Meant to Inspire Teachers and Students

Artwork and projects decorate the light blue walls of Inspired Teaching Demonstration School, an inquiry-based learning public charter school now in its eighth year.

A colorful “body map,” with the organs labeled, covers the door of one prekindergarten classroom. On the wall outside the other pre-K classroom hang drawings of guitars because the class read a picture book about the childhood of Jimi Hendrix when learning about musical instruments. Down the hall, the 3-year-old class has been experimenting with paints, both watercolors and temperas.

Everything displayed on the walls of the three-story building on Douglas Street NE in D.C.’s Ward 5 is student-made.

“Teachers really value our creativity here,” says Takhari Millner, a seventh-grader who has been attending ITDS since kindergarten.

Ranked a Tier 1 public charter school by the D.C. Public Charter School Board, ITDS opened in 2011 and serves 472 students in prekindergarten through eighth grade. There’s two classes per grade, except for seventh and eighth grade, which will each expand from one class to two when the school reaches its roughly 525-student capacity in 2020. For the 2018-19 school year, ITDS received 1,745 applications for 125 spots. Its waiting list currently has 913 students.

ITDS students have consistently outperformed their peers in both the public charter school sector and District of Columbia Public Schools on state exams, yet test prep and standardization are the antithesis of the school’s model. Born out of a partnership with the Center for Inspired Teaching, ITDS operates a demonstration school for the best practices in inquiry-based teaching and active learning methods.

For teachers by teachers

In 2009, the Center for Inspired Teaching, a national organization based out of D.C. that’s dedicated to teacher professionalism and experiential learning, brought together a group of educators to create a school that showcased the center’s instructional model.

Deborah Dantzler Williams, the founding head of school, previously worked as the center’s director of strategic partnerships.

“The center had partnerships with public schools around the city,” she says. “I’d talk with principals, wanting to share CIT’s philosophies, but often, they had looked up my background and seen that I came from an independent school environment. They were suspicious, thinking, ‘Well, you worked in schools that test and pick kids, so how can what you know be relevant to us? Where can we see this type of instructional model being done in a public school? On a typical budget?’ We couldn’t avoid those questions anymore.”

“Being a charter school was really our only option,” says Kate Keplinger, ITDS’s chief operating officer and lead author of the school’s charter. “Our mission is focused on public education, but we needed a place where we could be innovative and different. Within DCPS, we wouldn’t have the same freedom and ability to make the kinds of decisions that we needed to make about how we were going to teach within and staff our school.”

The Center for Inspired Teaching wanted to create a school that could be a changemaker in the realm of public education — a place where they could share best practices with educators, policymakers and community members. Part of that goal meant creating a place that could serve as a training site for teachers. Through the Inspired Teaching Residency Program, teachers can earn both their master’s in teaching and their D.C. teaching license through coursework and a residency year spent working in an ITDS classroom, under the supervision of an experienced teacher.

Teacher residents follow a “gradual release” training. First, they observe the experienced teacher; then they begin teaching small portions of the class; and finally, they take over the teaching entirely. During the second year of the program, teacher residents obtain a full-time teaching position in a D.C. public school. After successful completion of the residency, they must work an additional four years in D.C. public schools to receive full tuition reimbursement.

How to think, not what to think

To explain inquiry-based learning, ITDS’s leadership compares schooling to a taking a trip. At a traditional school, teachers decide where the journey (the learning) will start and end, but they also decide the vehicle needed for travel as well as all the sites that will be seen. At an inquiry-based school, teachers still pick the starting point and the destination, but the class helps choose the mode of travel and the route. Teachers navigate (keep students on track) without controlling the entirety of the expedition.

ITDS relies on outside curriculum — including Creative Curriculum, a research-based preschool curriculum that features exploration and discovery as pathways for learning, and Readers-Writers Workshop, where teachers act as reading-writing coaches showing students how to read and write rather than telling them — but there are no prescribed lesson plans. The curriculum and standards drive what students need to know; teacher and student interests determine how to get there.

For instance, in Ash Moser’s English language arts class, students had to meet a writing standard that required them to research a topic, take notes and communicate what they’d learned by creating a nonfiction text. Moser didn’t assign topics. Instead, he let the students choose. However, their nonfiction text had to be “a product with a purpose.” So one student researched allergies and made a brochure about them, which she is now handing out to doctor’s offices. Another student researched porcupines and created a placard for a zoo exhibit. She’s currently attempting to obtain permission to post it at D.C.’s famed National Zoo.

“When students get to see that there’s value in what they’re doing — a purpose to their education beyond getting a grade of passing a test — they see why education matters. Here, teachers are encouraged to make learning highly motivated and purposeful,” says Moser.

In the inquiry-based learning model, teachers are still considered providers of information, but they are also the instigators of student curiosity and provokers of original student thought.

“Our teachers are really kind,” says sixth-grader Tara Roberts. “They actually care about what you’re doing and how you do it. Before I came here, I was at a school where you could do the work you were assigned, and when you’d finished, you could play with Legos. I didn’t like that at all. The teaching style here is that you can do things in different ways and that your choices matter.”

“A pillar of our school is very much how to think, not what to think,” says Monisha Karnani, ITDS’s director of demonstration and outreach. “For instance, students don’t wear uniforms here. That was an intentional choice. As an adult, most professions don’t require uniforms. You have to decide for yourself, ‘What is appropriate dress in this context, and why?’ For all our rules, we explain the ‘why’ to students and allow room for conversation about that ‘why.’”

This ethos attracted teacher Tamas O’Doughda to the school. He’d gone on several interviews at other D.C. public schools before coming across ITDS. “From many of those, my impression of the culture was: ‘You must follow this lesson plan exactly,’” he says. “Here, the first question they asked me was ‘What’s your educational philosophy?’ And Ms. Dantzler Williams even said, ‘You have a lack of rigidity. That’s great.’ My last administrator would have seen that as a weakness, but here, the leadership sees the value in exploration. Everything doesn’t have to be mapped out. You don’t have to teach students in just one way.”

“The freedom to have some more out-of-the-box ideas in how to let students learn has really kept me here,” says science teacher Jodi Ash. “We’ve had a lot of fun teaching and learning science, and that’s had an impact on me as an educator and how my kids feel about science. They burst into songs when they hear words from the periodic table. There’s a lot of joy in learning here.”

Liane Alves, an ITDS prekindergarten teacher and former teacher resident, agrees. “Teaching here is both very fun and very challenging,” she says. “Because of the inquiry-based model, learning here is bottom-up, based on what students are interested in, rather than top-down, based on what I know. So I have to learn a lot because I have to research what they want to learn. I’ve researched robots, vehicles and city planning. This year, there’s a lot of interest in space.”

This school does everything differently

At ITDS, there isn’t a heavy reliance on technology. From third grade up, each student has their own tablet, but devices are only used if they can enhance learning, never merely to check a box, and the school has no SMART boards — another intentional choice.

Regardless, the Partnership for 21st Century Learning has identified ITDS as an exemplar school. The designation signals that the school uses 21st century learning initiatives that are successfully preparing students for college, career and life. At ITDS, that preparation comes from a school-wide emphasis on project-based learning as a method for enhancing students’ critical and creative thinking.

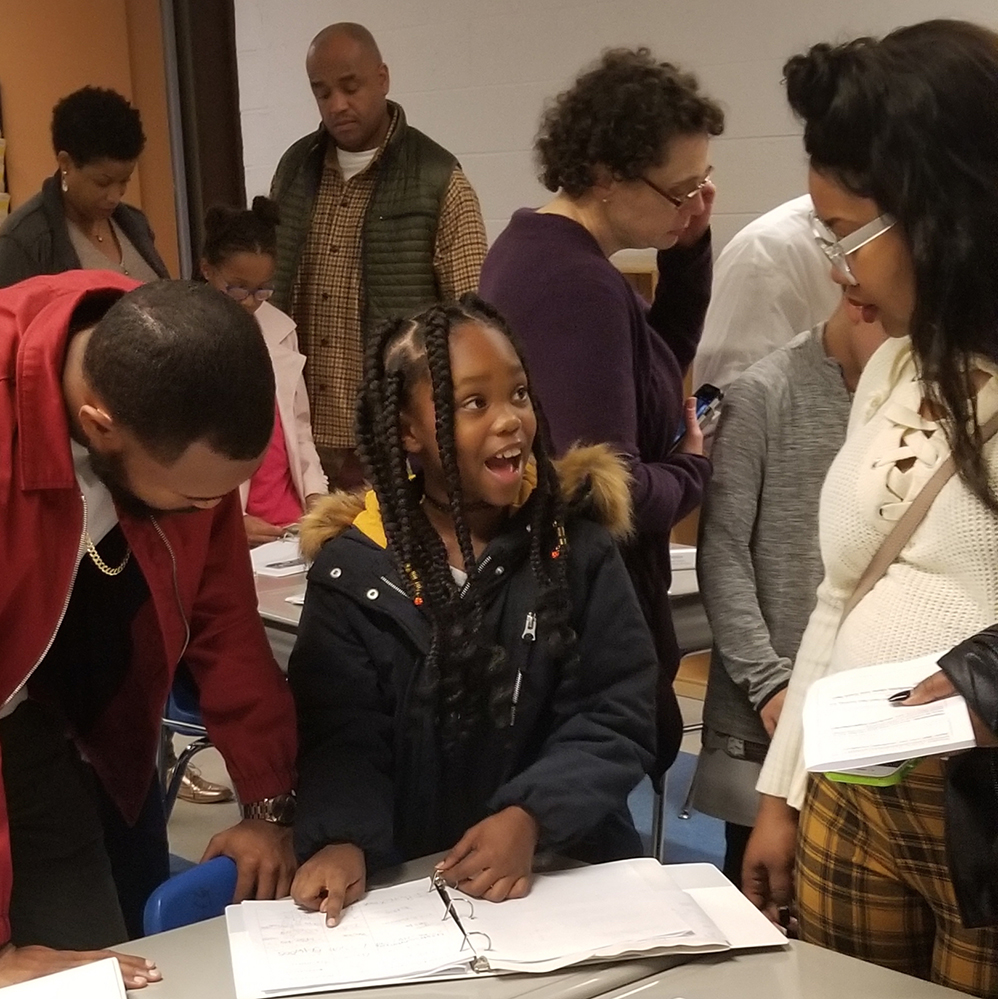

Each trimester, students complete culminating projects in their core subjects. At the end of the trimester, students show off their projects at “Learning Showcase,” an evening event where families come to see what the classes have been working on. It’s a great community builder, and school leaders say family participation is above 90 percent.

In Courtney McIntosh-Peter’s sixth-grade math class, students finished their study of ratios by examining Cubist artist’s Piet Mondrian’s Composition With Red, Blue and Yellow (1921). First, they determined the ratios of the colored squares in his art. Then they had to create art using assigned ratios. Finally, they had to create an original work of art and explain the ratios that they chose.

Last year, when Black Panther came out, Jodi Ash’s sixth-graders were working on their chemistry unit. As a class, they debated where, given what they knew about its composition, vibranium, the fictional metal from the film, would be located on the periodic table. Then Ash assigned each student a single element from which they had to derive a superpower. Based on the element’s properties, students created their own superhero franchise, complete with comic books, costumes and theme songs. They paraded through the school, singing their theme songs and wearing their costumes.

Ash Moser’s class also held a funeral procession for all the “dead words” they would no longer use in their writing. On the wall of his classroom is “Moser Hill Cemetery,” where lifeless words are laid to rest, marked by paper cutouts of tombstones that bear names like “Good,” “Bad,” “Awesome,” and “Cool.”

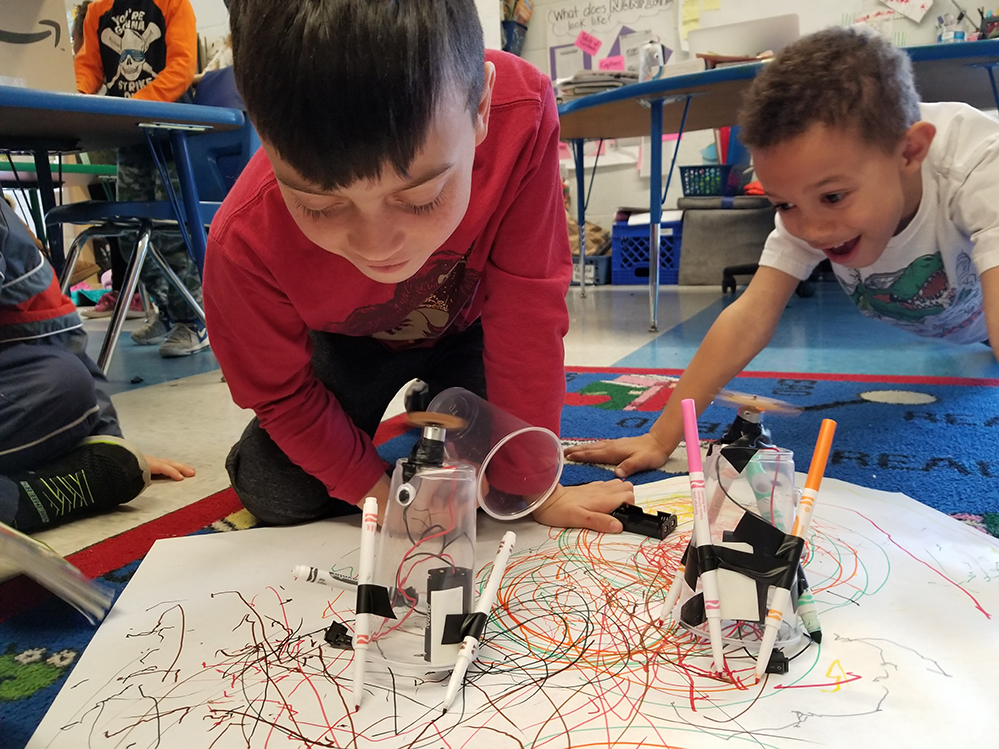

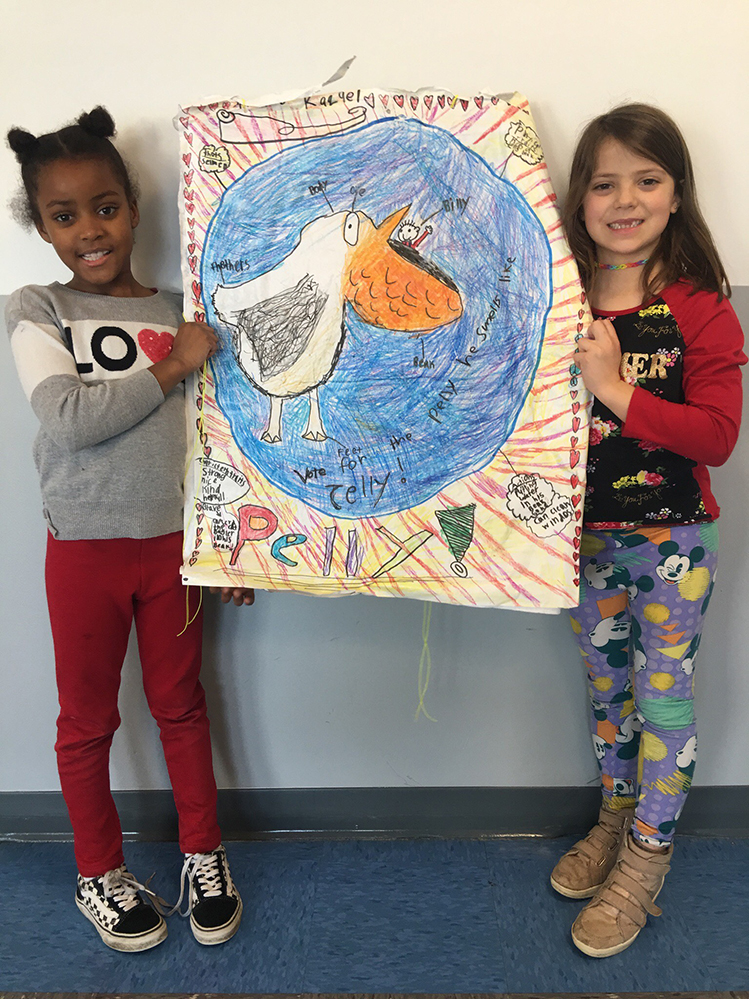

In Matthew Wong’s second-grade class, students created campaign posters for different characters from Roald Dahl’s books. In November, they held an election to determine the school’s favorite character. The winner, in a landslide victory, was Matilda. The standard the class was studying? Character development.

“This school does everything differently than other schools I’ve been to,” says fifth-grader Alexis Brown. “No other school that I know of does intersession.”

Intersession is the highlight of the school year for many students. During the week before winter and spring break, every adult in the building picks a topic they’d like to explore in depth with a small, mixed-grade group of students for four school days. Students then sign up for the session that interests them most. Previous options have included: martial arts, photography, creative writing, cooking, T-shirt design, winter engineering, improv, student newspaper and more.

But can it be replicated?

Many ITDS parents want the school to expand through 12th grade. Numerous community members want it to replicate. However, neither growth nor replication are in ITDS’s plans.

“The demonstration model was not meant to be replicated by us, but to be replicated by other schools,” says Karnani.

“The idea is to get this model perfected to a place where other schools can replicate it,” says Dantzler Williams. “We think we can reach more kids in the District of Columbia that way.”

The school welcomes visitors. This year, they’ve already hosted teachers and principals from DCPS, Montgomery County Public Schools, and the Alpine School District in Utah. However, questions remain about the practicality of widespread replication.

“CIT has always believed that teachers are the key agents for change,” says Keplinger. “But the real question is, how do they compare to the human resource person in a big central office? We only let people work here who are philosophically inclined to our beliefs, and we screen our staff heavily for that. You can’t replicate our model in a school that lacks the ability to make those decisions.”

ITDS is also a member of the Diverse Charter Schools Coalition, an organization dedicated to creating racially and socioeconomically diverse charter schools through advocacy, research and outreach. Its student population is racially diverse: 45 percent of students are white, 37 percent African-American, 7 percent Hispanic, 3 percent Asian and 9 percent multiracial. Fifty-nine percent of the faculty are people of color. The leadership works via recruitment efforts to keep it that way. However, only 22 percent of the students are designated as economically disadvantaged, a much lower number than both the 77 percent for all DCPS schools and those of many struggling district schools where teachers face challenges specific to educating children in poverty.

However, Dantzler Williams believes that the essential elements of the school — teacher voice and professionalism, the core beliefs and project-based learning — are applicable in schools throughout the District. And former teacher residents bring the training, philosophy and practices that they’ve learned at ITDS with them when they accept positions at the city’s other public schools.

“We still very much believe this model can be replicated,” says Dantzler Williams. “But we are still figuring out a lot of the key pieces. Like our students, we are learning on a regular basis.”

Thurgood Marshall Academy: A, B, C, F — Why This High School Never Gives Ds and Teaches Its Students to Think Like Lawyers

“Coats off, scarves off, hats off! Belts on; shirts tucked,” Stacey Stewart, Thurgood Marshall Academy’s director of student affairs, yells at the two lines of students waiting to check in and begin the school day.

“Ms. Stewart, I’m early today,” a student says as he approaches check-in.

“It’s 8:29. You are not early; you are on time,” she says, exasperated and amused. Check-in runs from 8 to 8:30 a.m. After students check in, they head downstairs for breakfast.

Nothing about morning check-in at Thurgood Marshall Academy (TMA) hints that there’s anything exceptional about the school, but a glass case near Stewart, filled with academic awards, reveals the truth: This is an extraordinary school.

Consistently ranked as a top-tier public charter school in Washington, D.C., Thurgood Marshall Academy is a law-themed school that serves about 400 students in ninth through 12th grades. Over 90 percent of students live in Wards 7 and 8, the city’s two poorest neighborhoods. Nearly 100 percent are African-American, and 61 percent are designated “at risk” by the Office of the State Superintendent, meaning they are at greater risk of dropping out based on their receipt of public assistance, food stamps, involvement with the D.C. Child and Family Services Agency, homeless status, or being older than expected for their grade.

The average ninth-grader enters TMA three to four years behind grade level.

Nevertheless, since TMA graduated its first class in 2005, 100 percent of graduates have been accepted into college, over 90 percent have enrolled in college within a year of graduating from high school, and 94 percent persist in college from freshman to sophomore year. The school’s cohort four-year graduation rate (a city calculation that also includes the status of students who have withdrawn or moved to different schools over the past four years) is 78.5 percent, higher than the statewide average of 68.5 percent, and significantly higher than the neighborhood’s district-run high schools, which have rates of 50 and 55 percent. For the past three years, student scores on D.C.’s standardized exams have been among the highest citywide for nonselective high schools.

“As a nonselective, freestanding high school, we don’t have a feeder pattern,” explains TMA’s executive director, Richard Pohlman. “We’re ready to take all kids who come through our doors, so our program has to be diverse enough to take both kids highly prepared and those significantly behind. Our systems and structures are a decade-plus old, but they’ve produced consistent results over that amount of time. What we’re doing works.”

So, what are they doing?

They’re exposing students to law-infused curriculum.

They’re increasing learning by supporting students and teachers.

And, they’re not giving Ds. The grading scale at TMA goes A, B, C, F.

Mastering the 5 essential legal skills

TMA’s goal is not for every student to become a lawyer but for all students to gain competency in the skills that lawyers rely on. The “five essential legal skills” — advocacy, argumentation, critical thinking, negotiation and research — are woven into the curriculum for all classes.

“We’re always learning about and growing our law theme,” says Pohlman. “It’s not easy to know what a broad mission statement looks like in practice, so we have to work at it. How do we teach skills that are useful for civic engagement? Skills that get kids into college and careers, but also help them become actively engaged democratic members of society? Our history teachers have been remarkable about that.”

Each year in history class, students must complete a law-related project that emphasizes the five legal skills. Previous projects include mock trials, soapbox speeches, issue-to-action projects and studies of the impact of federal legislation on D.C. Council legislation. In the 2017-18 school year, the social studies department arranged 18 educational trips for students, including a visit to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Students also participate in the school’s law-related programming. In ninth grade, students have Law Day six times a year, when they attend legal workshops hosted at and by local law firms. Sophomores spend eight half-days at Howard University, learning from professors about how law is present in their everyday lives.

During their junior year, students get to know a legal professional through the Law Firm Tutoring mentorship program. TMA partners each junior with a mentor at a local firm. Once a week, students travel to the firm (which provides meals and transportation) and have dinner with their mentor, who helps them with scholarship writing, SAT prep, college research, etc.

“Understanding the law and my rights has made me a better person outside of school,” says Devin Halliburton, a junior at TMA, whose Law Firm Tutoring mentor Yasmine Harik is an associate at Arnold & Porter.

Fellow student Ashleigh Miles agrees. “I’m not going to turn law into a career, and neither is Devin, but the information is good to know,” she says. “The law part, that’s what makes Thurgood unique. We get to meet new people and make connections in that world and learn from them.”

For those students who become interested in pursuing a law career, TMA offers more in-depth law courses. For instance, in Peer Court, students learn about how laws affect school policy, such as the Individuals with Disabilities Act and special education, and court cases, such as Morse v. Frederick, involving students’ free speech. In the 2007 case, the U.S. Supreme Court found a school official had not violated a student’s First Amendment rights by suspending him for displaying a banner proclaiming “Bong Hits 4 Jesus.” Another component of the class involves volunteering on a student-run court, which coordinates with the Office of Student Affairs to assign and monitor consequences for students who have committed minor disciplinary infractions.

“We teach students to advocate for themselves, so we want to listen to them when they do,” explains Pohlman. “Peer Court is a way of doing that. It lets students think about logical consequences for behavior.”

Peer Court, portfolio assessments, and food if you’re hungry

“Ms. Odu!” a student shouts. “Do you want to hear a joke?”

“Hmm. Do I want to hear a joke?” Ms. Odu, her ninth-grade English teacher, pauses. “Yeah, OK, go on, Kamani.”

“What’s the hottest place in a cold room?” Kamani asks. “The corner, because it’s always 90 degrees.” The class laughs, but no one louder than Kamani. Ms. Odu laughs with them.

“That was cute,” she says. “But now, we have to settle down and finish this assignment from the last class in 25 minutes because we can’t spend six years on it. And, remember, your quiz is on Monday. We don’t have school on Friday, so some of you will probably forget. But that’s OK. Because that’s your problem.”

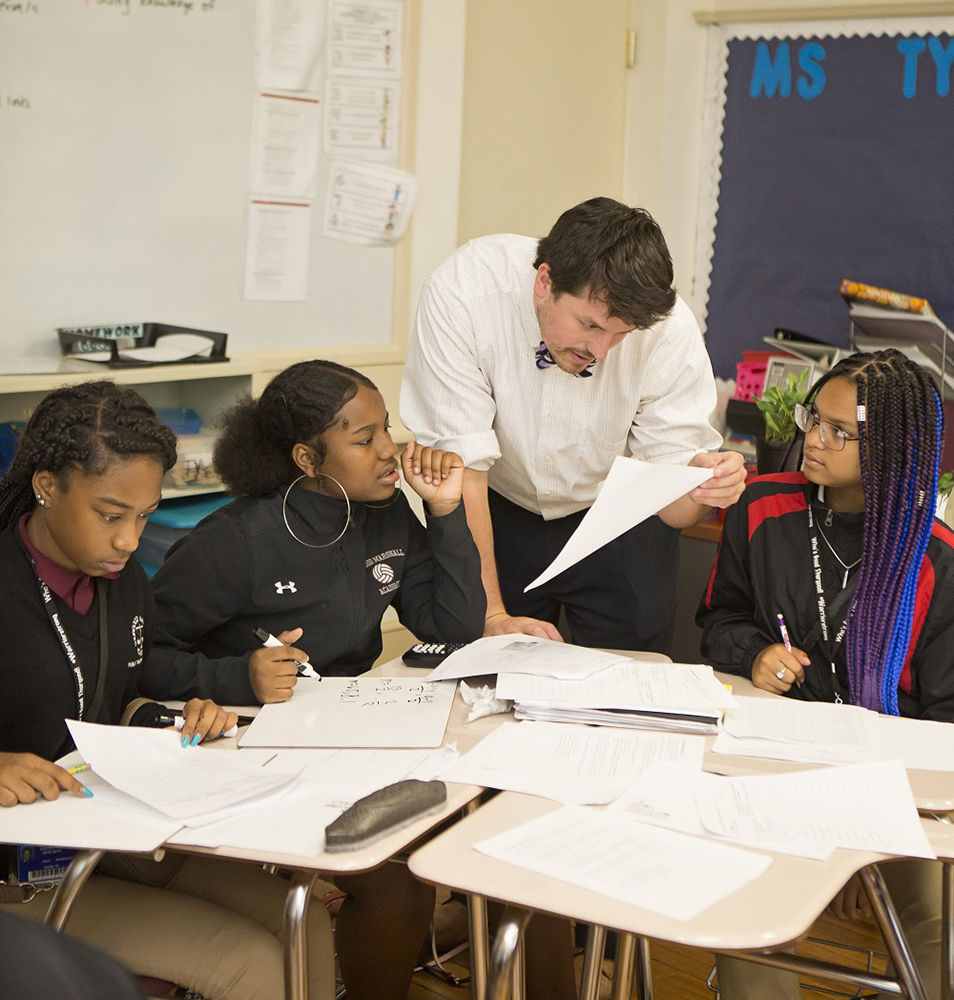

Kome Odu came to TMA in 2012 after teaching in Prince George’s County Public Schools in Maryland. “The standards here are so much higher than at my old school. That matters to me. There’s more rigor and organization and an expectation that kids do more, can do more,” she says. “The administration supports teachers. I like teaching literature to black kids, these kids. That’s what keeps me here.”

The school’s leadership believes that too often in urban education, teachers are asked to perform multiple roles beyond teaching, making it impossible for them to focus on improving their craft and, by extension, student learning.

“The foundation of our school is made from what happens in classrooms,” says Pohlman. “Our teachers’ job is to make sure instruction is great all day long. They need to be supported in that.”

At TMA, deans are in charge of managing school culture and student behavior while the heads of school focus on instructional delivery. Instructional leaders are made aware of behavioral issues, but the deans are responsible for handling those issues.

“We have people whose jobs are very distinct. Everyone needs to have a laser focus on their job to do it well, so we don’t expect teachers to be doing everyone else’s job,” says Pohlman. “We all talk and coordinate, but we have a place — a specific person — to send students to for specific issues and questions.”

Stacey Stewart, the director of student affairs, believes that this division helps assuage behavioral problems. “A lot of our kids have a lot of stuff going on at home, and their behavior is not always a reflection of what’s going on in the classroom,” she says.

The Office of Student Affairs supports students outside the classroom so that they’re prepared to learn in the classroom. Stewart anticipates potential causes of decreased motivation or disruptive behavior. Her office has boxes of snacks, toothbrushes, deodorant and other things. “If a kid’s upset because he doesn’t have clean clothes, I get him clothes,” she says. “If a student’s hungry, I get her a snack. I take that stuff away from them so that they can focus on learning.”

When behavioral issues do occur, TMA differentiates consequences based on both the seriousness of the infraction and the student. Peer Court assigns consequences for violations of TMA’s “no-brainers” — chewing gum, using devices in school, uniform violations, etc. — while Stewart’s office handles higher-level violations, such as fighting and willful disobedience.

“Some kids respond well to a call home,” Stewart says. “Others will move for one teacher because they have a relationship, but not for another, so bringing in that teacher to mediate a circle conversation helps. A lot of it is understanding what works to move that kid.”

But TMA’s leadership also expects students to own their behavior. The school uses a merit and demerit system. While students can work off demerits by gaining merits, if, at the end of the year, a student has more than 20 demerits, he or she won’t be promoted, regardless of academic performance. However, because grade-level deans host opportunities for students to earn merits over the summer, like classes focused on community service for the school or building positive relationships, this rarely happens. For the past three years, no student has been held back because of behavioral infractions.

Students also reflect upon their yearly progress through a portfolio assessment. Each spring, they give a formal presentation to three faculty members during which students examine their academic performance as well as their behavioral record and overall contribution to the school. And they turn in a portfolio of the materials they intend to speak about.

“I get so nervous for portfolio,” says Halliburton, the junior. “It can be in front of teachers you don’t know, and you’ve got to talk for, like, 45 minutes. They don’t talk. They just write stuff down and look through your binder. You’re explaining everything you did — like your school work and behavior — and why. But it actually really helps me. I save my portfolio projects and look at them to improve.”

A school without Ds

“When I came here in ninth grade, I was behind in reading,” Halliburton says. “My first semester, I got a 69 in English on my report card. At my old school, that would have been a D, but here I was seeing an F. That was like, whoa, I need to start tightening myself up. I’m supposed to be preparing for college.”

Halliburton’s reaction is exactly why TMA grades on an A, B, C, F scale, where anything less than a 70 is an F. The school’s leadership believes that if students don’t know at least 70 percent of the material, they won’t be prepared to pass at the next level. The lack of Ds is not a punishment; it’s a success strategy.

“It’s stressful for freshmen,” Pohlman admits. “Many are accustomed to always just getting by, and suddenly, sliding by is failing. We have a lot of resources to support kids when they’re failing, but they’ve got to work hard.”

Mills, Halliburton’s classmate, knows exactly what he means. “At my middle school, they just passed you on. It didn’t really matter if you got the curriculum or not,” she says. “When I came here, I failed Algebra I the whole first year. But then when I did get to geometry, I went to office hours. I got more help. I didn’t fail geometry.”

Students are eligible to take up to two courses per summer if they fail their courses. If students do not retake a failed course over summer, they either receive an alternative schedule for the following year, which includes the retake, or they retake the course in a subsequent summer. However, for courses that have a specified order, as in Mills’s case, students must pass the prerequisite before moving on to the next level.

Since most ninth-graders enter TMA below grade level, freshman and sophomores take double-block English and math classes. They have twice as much classroom instruction as their peers at traditional high school programs. These double-blocks are a cornerstone of TMA’s success at raising student achievement. Other academic supports include a Summer Prep program that helps students transition into TMA’s rigorous academic environment, an SAT prep class, and a Senior Seminar in which students receive intensive coaching on the college application process, help with scholarships, and lessons on transitioning to college life. The school has a robust college counseling department, with three full-time college counselors.

“Our college acceptance rate is [far] higher than the national average for low-income communities, so we tell parents what our system looks like and ask them to trust it,” Pohlman says. At the end of the first quarter, many parents call him, upset or angry, because their student has never had an F before. “Well, they have an F now,” he tells them. “Let’s help them get out of it.”

“Our ultimate goal is not to have kids take remedial classes in college,” says Stewart. “Because that’s debt on top of debt.”

One national study that looked at 911 two- and four-year colleges found that 96 percent of students there were placed in remedial classes in 2014-15. Remedial classes carry no credits, but enrolled students who cannot pass freshman-level course entrance exams must complete and pay for them before they can enter into credit-bearing courses. Research has shown that a large percentage of students placed into remedial courses drop out before graduating college, and often before even finishing the course.

Both Halliburton and Mills agree that “Thurgood is hard,” but, by the second year, students adjust to the rigor. Moreover, they regard the high standards as the manifestation of the faculty’s belief in their abilities.

“Everyone here wants me to succeed,” Halliburton says. “Teachers have office hours before and after school, and they’ll come to you to make sure you’re straight with their class if they think you need help.”

It’s this combination of rigor and support that draws many parents and students to TMA. The school’s success with students, as well as the demands placed on them, are well known in the community.

“We don’t lure families here under the false pretenses that everyone passes,” Pohlman says. “The part of school choice that really matters is that you have a system with a lot of different choices and that you provide families with as much transparency as you can so that they can make a choice. We’re an important part of that system in D.C.”

Digital Pioneers Academy: Creating the Next Generation of Digital Innovators at Washington, D.C.’s First Computer Science-Focused Middle School

“When I finish writing the statement, that cat will move,” promises Deshaunte’ Goldsmith, a sixth-grader at Digital Pioneers Academy Public Charter School. She presses enter on the keyboard and, sure enough, the animated cat on her screen begins to pace back and forth.

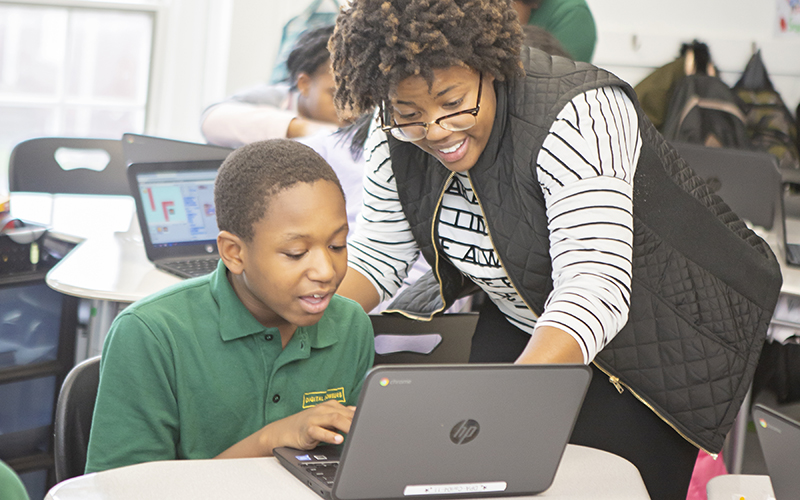

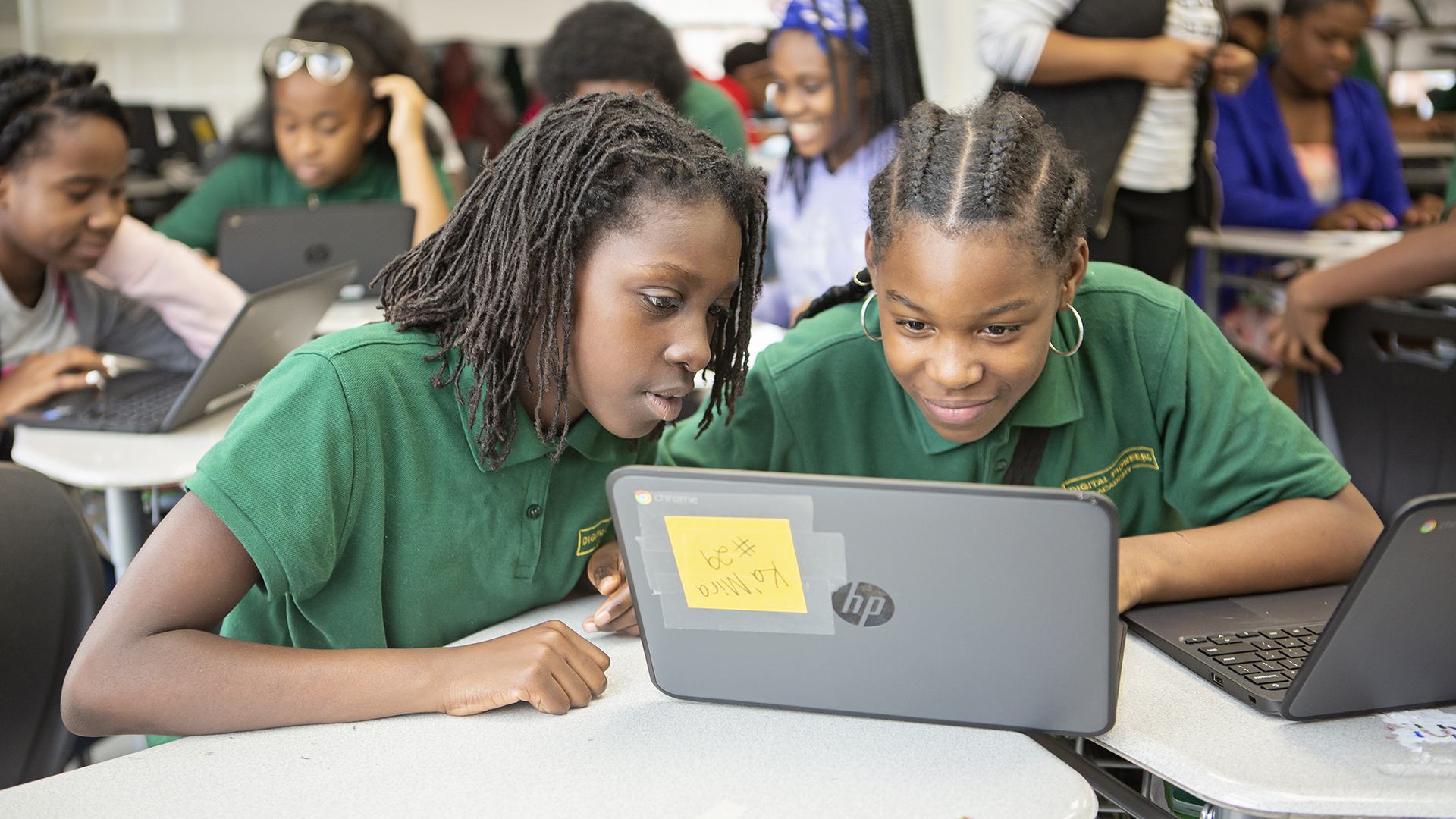

Goldsmith is a member of the founding class at the school known as DPA, Washington, D.C.’s first computer science-focused middle school. Opened in August, the school is small, serving about 120 sixth-grade students across four classes, but has plans to build out to 12th grade. Every day, students take computer science as a part of their core curriculum.

Today, in computer science, Goldsmith is learning how to write conditional statements — such as if the space bar is pressed, the cat will jump — using MIT’s animation-based platform Scratch. First, the students have to identify conditional statements, and then they have to write their own. At the end of class, they have to find and correct the error intentionally planted in the teacher’s code.

“The error’s in the third line of code,” Goldsmith says. “It’s missing part of the conditional statement.”

DPA occupies the second floor of Washington Heights Baptist Church in the Hillcrest neighborhood of the city’s seventh ward. Ninety-eight percent of the students come from wards seven and eight, D.C.’s poorest neighborhoods, and, because DPA’s leadership recruited heavily in the local area, two-thirds of the students went to the neighborhood elementary schools.

“My decision to go to this school was sort of last minute,” says Goldsmith. “I was waitlisted at Friendship Charter School. Then I heard about this school, and I decided I wanted to come here and learn about code. All of the teachers here have really supported me, and this is one of my favorite classes. I’m happy I ended up here.”

Lamontae Allen, Goldsmith’s classmate, or teammate as they are known at DPA, also loves the computer science curriculum.

“Computer science is my favorite class,” he said. “I like to play video games. When I grow up, I want to be a famous YouTuber, but if that doesn’t work out, I might make my own computer game, and learning all of this will help with that.”

Today, only 40 percent of America’s K-12 schools teach computer programming, and computer science-focused schools like DPA that do not require admissions tests or screen their applicants are rare. Low-income families often lack access to technology, and the racial achievement gap in the tech industry is well documented. Less than 3 percent of Google’s workforce is African American.

“Our mission is very simple,” says Mashea Ashton, DPA’s founder and the head of school. “We want to develop the next generation of innovators. We want our students not just to consume the digital economy, but to be a part of creating it.”

A veteran educator embraces comp sci

With almost 20 years of experience teaching in and running public charter schools, Ashton knew she wanted to leverage her experience as an educational leader to positively impact Southeast Washington, D.C. — a historically underserved neighborhood she cares deeply about. Ashton began her career as a special education teacher just down the street from DPA’s current location, and her husband, a sixth-generation Washingtonian, grew up in the neighborhood.

Ashton herself has no computer science background. “I took one computer science course at the College of William and Mary back before they even had email,” she jokes. “However, three years ago, when I began thinking about opening a school, I thought about a college prep model, but the more I thought about students and families and options, the more I thought about the importance of being career ready. Then, I saw the data about how many high-paid, high-demand jobs in computing go unfilled every year.”

DPA’s curriculum is a modified version of the academic program developed by RePublic Schools, a network of charter schools throughout the South that teaches computer coding daily as part of its college prep curriculum. With this curriculum, DPA students begin by working on elementary programs like Scratch before learning two of the core internet technologies, the markup languages HTML and CSS, or Cascading Style Sheets, which determines the look and layout of a webpage’s content. They eventually move on to JavaScript, a more advanced language and the third of the core internet technologies. After mastering JavaScript, students will have the opportunity to explore other advanced programming languages such as Python and R.

Although DPA currently holds a charter only for a middle school, Ashton plans to apply to expand the school through high school, building up one grade at a time. During high school, students will be expected to pass the Advanced Placement computer science exam in 10th grade, she said, and become fluent in two coding languages by the time they graduate. Juniors and seniors will also participate in internships and work-study programs that allow them to gain real-world experience in the tech sector.

DPA is already building a pipeline of partnerships with tech firms, like Microsoft and Deloitte, and three times a year, middle schoolers will have “expeditions,” three-day experiences where they demonstrate some of the coding skills they’ve learned to tech experts before visiting the experts’ workplaces.

“When you think about the job quality and the job opportunities that our students will have because they had one hour of computer science each day from sixth to 12th grade … it’s incredible,” says Crystal Bryant, a STEM teacher at DPA. “It’s refreshing to see someone like Mashea come in with a vision to change the trajectory of the lives of kids in this area.”

Founding a school that celebrates science

When designing DPA, Ashton and her team researched broadly to learn about the best models for a computer science-focused school. In the spring of 2017, Ashton taught an elective, “Design the Academy of the Future,” to ninth-graders at Washington Leadership Academy Public Charter School, a technology-focused high school in D.C. She heard from students about the factors of their education that have had the greatest impact on their motivation and learning. Understanding the real-world application of the skills they were learning ranked at the top of the list.

“Students didn’t need to be told about the number of high-paying computing jobs available; they needed to have real-world experiences, to see the real-world connections for what they were learning,” says Ashton. “They wanted to know the ‘why’ for everything. ‘Why am I taking notes? Why am I reading Shakespeare? Why am I doing Scratch?’”

Ashton also spoke with the leaders of the Academy for Software Engineering, a computer science-focused school in New York City. The school’s leaders said they had initially recruited tech experts to serve as the teachers, but they ultimately discovered that they needed people who were experts in instructional delivery, classroom management and working with teenagers. The RePublic curriculum, however, is not expert-dependent, so Ashton could recruit widely for her teaching staff.

“None of our teachers had ever taught computer science as a core part of the curriculum before,” she says. “We recruited educators who believed in our mission, had the best achievement record for working with kids like ours, and who were excited to be on a founding team, which is very different from a regular teaching job.”

What being a founding teacher means, Ashton says, is long, hard hours and owning the successes and failures of the school. “There’s the opportunity for growth, but there’s also going to be some failing forward, which is an important part of growth and a value we attempt to impart to our students,” she says. “I do think our teachers are feeling the success of what it’s like to work together on a team with a shared mission and vision where everyone is accountable.”

Bryant, the STEM teacher, came to DPA because she felt that in urban education, science often isn’t considered as important by school administrations as math and English, the major testing subjects. She wanted to move to a place that celebrated science and computer science, rather than treating it as an elective. At DPA, she was given the opportunity to build a STEM program.

“A lot of people warned me about joining a founding team. ‘It’s a lot of work,’ they kept saying, but I think it’s going to be rewarding to look back and see all of the computer scientists that our school has produced and know I helped create that,” she says.

“No one is just a teacher here,” adds STEM teacher Ashley Pettway. “A lot of times in urban education, you feel like you’re a part of a system where you have no control, but here, anything that we dream up for our kids, so long as it’s mission- and vision-aligned, is supported. We can do it. I’ve never worked in a place like that.”

High empathy, high expectations

DPA’s classrooms have arched attic ceilings and an airy, homey feel. The school renovated the second floor of the building before moving in, creating four large classrooms and some smaller meeting rooms. Backpacks are hung along the classroom walls, and there are comfortable sitting areas for students in addition to more traditional desks.

“Our scholars learn better when the environment is conducive to learning,” says Ashton. “I hope they feel like these are their rooms.”

To minimize transition times, students don’t switch classrooms; instead, the teachers do. Each class always has two adults, the classroom teacher and an assistant, who is often a dean or another member of the administrative team.

The school day runs from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., except on Wednesdays, which are half-days. Students have study hall, math, computer science, social studies or science, an intervention period for struggling students, two classes of English Language Arts and recess, daily. There’s a break in the morning and a second one in the afternoon. There’s also an a.m. and p.m. community meeting and a mandatory enrichment activity — like kickball, dance, creating holiday cards and more — from 4 to 5 p.m. It’s a long day, but many of the students come in significantly behind grade level, so there’s a lot of work to be done. When the school year began, only 20 percent of the founding class was on grade level in both reading and math.

“We tell our scholars that if they want to achieve, then they have to outwork everyone, and they’re learning and beginning to own that,” says Ashton.

Classmates give each other “snaps,” impromptu snapping, to celebrate when a teammate does something well. There’s also a school-wide hand sign for “giving magic,” which is wiggling fingers at a teammate to send good them vibes.

“We are team, so we want to support one another, but we don’t have a lot of spare time. Our silent celebrations give students a lot of joy, but they aren’t disruptive to learning,” says Ashton.

Students can also earn a “professional” point each class period if they demonstrate behavior, like optimism, empathy, and growth, that reflects the school’s values. Professional behavior earns a point; unprofessional behavior, like talking back to a teacher or putting your head down in class, loses a point; and neutral behavior results in no change. Students can redeem themselves throughout the period; it’s what they’ve done by the end of class that matters. The system promotes the idea that students have control over, and can change, their behavior. Every morning students fill out their daily behavior goals for each period, and every afternoon they reflect on whether they met those goals.

“Professional and unprofessional is language that kids really understand,” says Bryant. “They know adults have to be professional, so they see the real-world connection. It’s very clear cut, which makes it easy for them to articulate reflections on their behavior and even write things like, ‘I was slouching in my seat and not participating yesterday so I wasn’t being professional.’”

If a student has a “community violation” — swearing at a teacher, starting a fight, etc. — then they receive an automatic “unprofessional” and are removed to the “reset room” for the remainder of the period. There, they fill out a reflection on their behavior and brainstorm how to make amends to the teacher and the community before returning to their next class.

Students can spend professional points at the school store. They can purchase dress-down days, Subway cards, a chance to visit friends in another class during break and more. However, the four students who have the most professional points at the end of the week get a pass to “The Lab,” where video games, a movie projector, a basketball hoop and more await. Staff asked the students what they wanted prior to stocking The Lab.

“There are Xboxes and TVs and everything,” says Pettway. “The first time I went into The Lab, I thought, ‘It looks like a Dave & Busters.’ I took photos of it to show the kids. It’s such a positive, consistent motivator for them. Ms. Ashton plays Fortnite [a phenomenally popular online game] with them in there. It’s great.”

“School and learning should be fun,” says Ashton. “We do want them to develop intrinsic motivation, but we also want them to understand that hard work and positive actions ultimately have positive consequences.”

“I appreciate that this is a very different experience for our kids than many are used to,” says Bryant. “I have been an urban educator for eight years, and I feel like our kids are constantly being punished for being children or for the things they don’t have. I appreciate that I’ve found a school where the goal is to remove all obstacles that keep kids from learning and then hold them accountable for their learning.”

“It’s called ‘high empathy, high expectations,” says Pettway. “And it’s a model that’s working for our kids.”

Ingenuity Prep: At D.C.’s Ingenuity Prep, Personalized Learning Hasn’t Replaced Teacher Time; It’s Put the Focus Back on Small Groups

When Aaron Cuny and Will Stoetzer were thinking about how they wanted to structure their own D.C. charter school back in 2012, they kept returning to the same question: “When were we doing the best work for kids?”

“For both of us, it came down to teaching in a small group setting, where you could think about how to reach kids individually rather than spending the majority of time and mental energy thinking about classroom management,” says Stoetzer.

Stoetzer was a special education teacher and Cuny a resident principal-in-training at D.C. Bilingual Public Charter School, a top-ranked elementary school in one of Washington’s middle-income neighborhoods. Both felt the city lacked quality educational options for kids in the neighborhoods that needed them most.

“In pockets across D.C., some schools had shown that when adults got it right, there was success at educating low-income kids,” says Stoetzer. “Schools like KIPP and D.C. Prep have been very purposeful about producing academic results for low-income kids. Their success inspired us, but we had differences in perspective about how that success might be accomplished.”

When they opened Ingenuity Prep a year later with Cuny as CEO and Stoetzer as COO, they located it in Ward 8, Washington’s poorest neighborhood, and built two essential components into the school’s design so that small group learning could be its main focus: co-teaching and computer-based learning.

Computer-based learning and personalized learning are often faulted for taking the teacher out of the equation too much, but in the case of Ingenuity Prep, they have been employed to the opposite effect.

“Digital content became a good way for us to deliver high-level, engaging content to kids, but the end goal was never to deliver content digitally,” says Stoetzer, whose special education background strongly informed his thinking about the school’s design when it came to small group instruction, personalized learning and differentiation. “All of the pieces of our model were driven by finding the best ways to maximize the time spent in small groups.”

Rarely in groups larger than 15

Ingenuity Prep serves 496 students in grades pre-K-3 to 5, with plans to expand to eighth grade. There are two to three classes per grade, each with between 25 and 30 students (24 in preschool). Each preschool classroom has three teachers, and in kindergarten and above, each classroom has two lead content area teachers, one specialized in math, the other in literacy.

There’s also a literacy apprentice who teaches across two classrooms. When students are in literacy class, the literacy-lead teacher and the apprentice co-teach the content. When students are in math class, the lead math teacher from one classroom comes to the other classroom for co-teaching support.

The school hosts resident teachers from the Urban Teachers program, and school leadership says the partnership has been integral to making Ingenuity Prep’s group model function. Resident teachers already have a bachelor’s degree, but the program allows them to work toward a master’s in education, including certifications in special education and their specific content areas. After the first year, Urban Teachers places its residents as full-time paid staff members in schools — usually the ones where they had already been teaching — where they can finish out the program’s remaining three years. Ingenuity Prep currently has 11 resident teachers.

Ingenuity Prep incorporates computer-based learning into the curriculum, a practice known as blended learning. In kindergarten and above, each student has access to a Chromebook and a student web portal, which contains different online educational programs like Lexia Reading and STMath. Teachers blend the digital content into the curriculum to target individual student needs and provide students with independent practice in subject-area knowledge.

Aside from the benefits of exposing students to blended learning, the goal of Ingenuity Prep’s learning model has always been more one-on-one time between teacher and student. Students spend less than 10 percent of their time learning in groups larger than 15 students. Maud Cooke-Nesme, a kindergarten literacy teacher, believes the computer-based learning has been important in achieving this.

“The use of technology really helps us as teachers because it gives us the ability to have the differentiated time in smaller groups,” she says.

‘They often feel like they aren’t in class, even though they are’

The implementation of the Ingenuity Prep model looks slightly different depending on the grade level.

In pre-K classrooms, play-based learning takes the place of computer-based learning. Students spend much of the day in “centers,” where they choose from a variety of activity stations like art, music and movement, and dramatic play — in which the preschoolers take on the role of adults in everyday situations and careers. As the students rotate through the centers, the lead teacher pulls out small groups to give them formal, personalized instruction in literacy and math. There are also some large group activities, like “Mindfulness,” a short time after recess during which students practice guided deep breathing and feeling their heartbeats.

From kindergarten to fifth grade, the Ingenuity Prep model for literacy hits its stride. Students spend a significant amount of time in small groups assembled by relatively similar ability level, rotating through different learning activities, from direct instruction to guided practice and independent, computer-based practice. While there’s teacher flexibility in the model’s implementation, all classrooms must have certain components essential to its success: a classroom library, a carpeted open space, a large group instruction area and small group instruction spaces.

In a kindergarten classroom, three groups are rotating through different literacy practice activities. Six students sit in two rows of desk, facing the front of the room, as they practice reading skills using Lexia on their Chromebooks. These students are on different levels from one another, progressing through the program at their own pace.

“Students like having that independent time on the computers,” says Avi Worrell, a second-grade literacy teacher. “They often feel like they aren’t in class, even though they are. They’re learning, but it’s fun and competitive learning.”

A second group of eight students sits at a semi-circle table, facing lead teacher Amber Morales. Morales is conducting guided reading, and she’s targeted both the text and the learning objective to this group’s specific skill level. The students are practicing sight words, with a focus on the word “where.” They follow along, tracking the text with their fingers, as Morales reads aloud and asks them questions about the story.

The last group of 10 students is on the other side of the room in a much more traditional classroom setup. They’re in rows of desks, facing the teacher and the board. Here, Urban Teachers resident Michaura Rivera is using direct instruction to teach phonetics and writing. Students practice drawing their letters on individual whiteboards, and Rivera monitors their progress.

“I really like changing through the groups because we have guided reading and instruction with our teachers, but we also go onto computers to practice on our own,” says Jahari’ Rose, a fifth-grader who has been at the school since kindergarten. “Lexia really helped us learn new sight words, how to read faster and how to find the meaning of a story.”

In a second-grade classroom, there are still designated spaces for small and large group instruction; however, because these students are more capable of self-monitoring their behavior than those in kindergarten, the library area and open space are larger, creating a cozy, independent reading environment.

In this class, one group of students is working on computer-based programs. Another group is around a table, working on a guided writing project with the lead teacher. And the third group of students are lying on the carpeted space in the library area. They’re practicing independent reading; they’ve chosen books from the shelf marked at their current reading level, as well as two books from the level above.

In a fifth-grade classroom, the setup looks more traditional, with the majority of the desks facing the front of the room and the teachers. There’s a Chromebook on each desk because students are working on writing in a large group activity. There’s still an area for small group instruction and a library area with open space. However, both are much smaller than in the lower grade levels.

Overall, math lessons schoolwide involve more large group instruction than literacy; teachers want a more heterogeneous group in terms of student ability level so that struggling students can learn by watching stronger students solve problems. Classes still incorporate the rotational model and blended learning, but often the lead teacher will perform direct instruction with a larger group while the assisting teacher pulls out small groups of students who need extra help.

“The school isn’t super descriptive on how to implement the model,” says Stoetzer, who recently stepped into the interim CEO role at Ingenuity Prep. “We make sure we have excellent teachers who are familiar with the model, but there’s adaptability in how to make the best use of it. After all, they know their students’ needs best.”

Intensive coaching, listening to teachers

“I’ve never been in a school that puts so much attention to detail in terms of content, organization and planning,” says Ashleigh Coleman, a pre-K-4 teacher. “The leadership really values [teacher] feedback here, and they encourage work-life balance. At other places where I’ve worked, teachers are workhorses. They’re expected to do whatever it takes to get the job done, but they aren’t listened to.”

School leadership admits that balance wasn’t always there; they’ve been very intentional about creating it. They use surveys to measure the adult culture in the building. They’ve allotted extra time for planning during the school day. And they have a robust teacher-coaching program in which school leaders observe teachers once a week.

“I worked at another school where I received pretty much no coaching whatsoever,” says kindergarten teacher Cook-Nesme. “One of the main things that attracted me here was the frequency of coaching. The coaching is specialized for literacy or math, so the feedback I receive makes sense to where I am in my development as a teacher.”

The coaching also helps create a uniform culture of high expectations.

“I previously taught at a Head Start program,” says Molly Karsh, a pre-K-3 teacher. “I have really come to appreciate the high expectations for both students and staff here. There, my kids left for kindergarten without being able to write their names. Here, my students talk about paleontology. There, my kids could not sit quietly on the carpet and learn with minimal distractions because we didn’t have that culture set in our classrooms, and I didn’t know it was possible to set it because I didn’t have the coaching or tools for handling distractions.”

This embedded culture of coaching develops a special relationship between leadership and teachers. All of the instructional leaders were once teachers, and many were once teachers at Ingenuity Prep. JaQuan Bryant, the co-principal of kindergarten through second grade, came to Ingenuity Prep as a first-grade teacher. He believes he benefited greatly from the coaching.

“But it’s interesting because some of my cousins are also in education,” he says. “When I first started here, I told them that leadership videoed me, and they freaked out. They said, ‘I would never let them do that. I’d have the union rep come in.’ But I think you need to have that sort of relationship between instructional leadership and staff to move the needle for kids. They’ve got to be able to hop into a classroom at any time. There’s got to be that trust.”

Teaching kids in trauma

“They let us have fun here, like on pajama day I got to wear my Batman onesie, but they ask us to think about our actions too,” says fifth-grader Jaiden Robinson. “The only downside about this place is the food.”

“Especially the pancakes — you can make Play-Doh out of them,” adds his classmate Dajon Walker, who has been at the school since third grade. “At my old school, the food was good. I can’t lie about that. But there was a lot of chaos. There were fights every day; it was a rampage. We didn’t listen to teachers. We just ran around and did what we wanted.”

His peer Marcellus Dyson also came to Ingenuity Prep in third grade. “In second grade, I got into a lot of fights because people kept messing with me,” he says. “There’s less fights here because they take care of it here right away and send kids to behavioral support.”

Ingenuity Prep has six full-time behavioral support specialists. If a student causes a disruption in class, the teacher texts one of the specialists, who then removes the student. The aim is to return the student to class as quickly as possible. However, there is a “reset room,” which students call behavioral support, for those who aren’t ready to go back to class immediately. There, students reflect on their behavior.

“I’ve been to behavioral support, and it’s effective,” says fifth-grader Zainah Williams. “They ask you why you’re in there, and you have to complete this worksheet about what you’d do better next time. Then, they ask you if you’re calm enough to go back to class. It helps me calm down so I can go back.”

Ninety-seven percent of Ingenuity Prep students are African-American, and the Office of the State Superintendent of Education has designated 60 percent of its students as economically disadvantaged. The state office also labeled 66 percent of students “at risk,” meaning they are more likely to drop out based on their receipt of public assistance, receipt of food stamps, involvement with the D.C. Child and Family Services Agency, homeless status, or being older than expected for their grade.

Many of the school’s students experience trauma at home, and their behavior is not always a reflection of what’s going on in class. Every teacher at the school has been trained in crisis intervention management. Student and family support specialists, special education teachers, the speech therapist and counselors also complete a deeper-level training. There’s also a full-time social worker and psychologist, and there are no security officers. The school screens staff during hiring to ensure that their values align with the school’s mission to educate low-income students with empathy and understanding.

“I grew up low-income in this neighborhood,” says third-grade teacher Davian Morgan. “But then my mom went back to school and then I went to school, so I understand the power education had in lifting us above the poverty line and into the middle class. I want for these kids to see how many doors open if you take your education seriously.”

Bryant, the K-2 co-principal, grew up in a similar neighborhood in East Oakland, California. “What keeps me at this school is that we believe every kid deserves access to an education equivalent to that of their affluent peers, an education that will allow them to be the architects of their own futures.”

The problem with replication