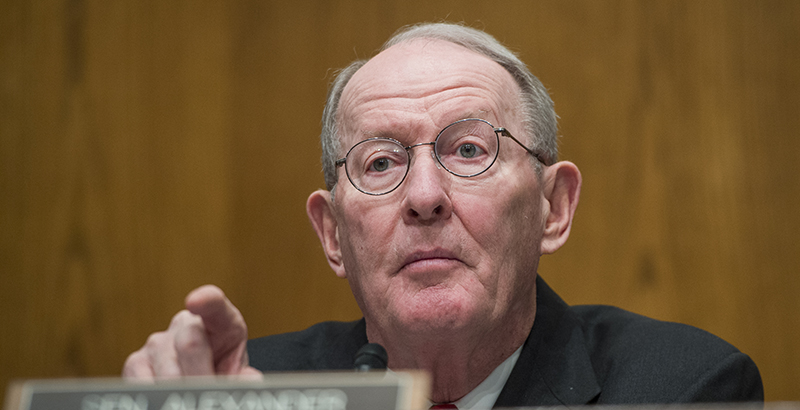

Lamar Alexander’s White Whale: Will 2018 Be the Year the Education Veteran Finally Gets His Chance to Rewrite the Higher Ed Act?

The themes in the New York Times article are familiar ones in debates about higher education: questions about the value of a college education, diversity on campus, the roles of political correctness and free speech.

Its opening paragraph touches on a president who has “barely mentioned” colleges, an “absence of any strategy” for coupling an improvement in higher ed with K-12 reforms, and even a “fundamental rethinking about what colleges do and how they ought to do it.”

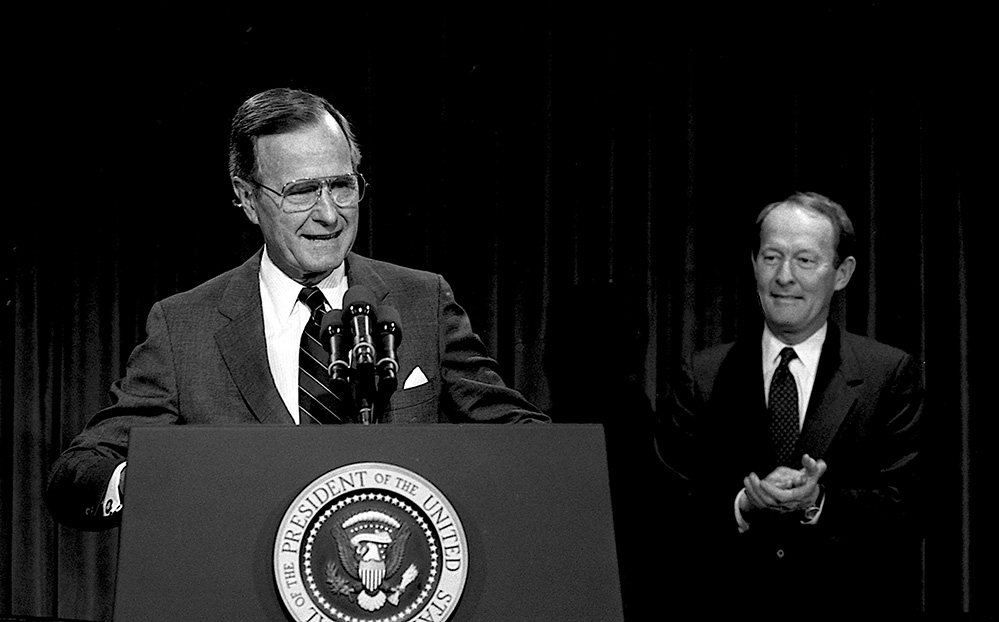

But the article wasn’t written last month, or last year, or even last decade. It’s more than 25 years old, its headline touting the “Clash of ’91: Higher Education Feels the Heat.”

Those same questions are again plaguing policymakers: how Americans value higher education, particularly as Republicans and supporters of President Donald Trump question it; what the role of campuses is as a venue for protest; and how colleges can keep pace with current technological innovation while preparing students for an evolving job market.

Another thing that hasn’t changed: the presence of Lamar Alexander. As education secretary under President George H.W. Bush, he played a key role in the fight 27 years ago, and now, as chair of the Senate education committee, he is in charge of helping to resolve the “Clash of ’18,” as it were, over higher education.

Rewriting the Higher Education Act is something of a white whale for Alexander, an elusive prize that he has sought for years. Whether 2018 is the year he finally catches it — after decades in public service, including 15 years in the Senate — could come down to how well he manages the timing and an array of entrenched interests.

The Tennessee Republican has worked in higher education policy in some capacity for nearly his entire political career, including stints as Tennessee governor and president of the state’s flagship public university. He was active in higher ed policy even while a student himself, using his position as editor of the campus newspaper to call for total integration of Vanderbilt University in 1962, condemning the administration’s policy of admitting black students to only some programs as “cowardly.”

The Higher Education Act, originally written in 1965 and last reauthorized in 2008, governs how more than $100 billion in federal dollars are spent every year, the vast majority on student loans and grants.

“It needs to be a student-focused act, and we want to make it simpler and easier for students to apply for federal aid for college and repay their loans,” Alexander told The 74 in a brief hallway interview at the Capitol last week as he rushed to floor votes after a hearing on the opioid crisis.

He also cited encouraging more innovation in higher ed, like competency-based education, and cutting down on the “jungle of red tape” of federal regulations as among his goals.

“If there is somebody who has demonstrated their ability to sort of push something forward once they have their mind set on it, it is Alexander.”

—Tamara Hiler, senior policy adviser, Third Way

The headwinds against a reauthorization are stiff.

The current election year means both a compressed congressional calendar, as members take time off to campaign, and a general wariness against taking any potentially politically risky votes. The law has been due for reauthorization since 2013, with seemingly no consequences for Congress’s failure to do so on time. The parties remain far apart on key issues, such as regulation of for-profit colleges.

Yet if anyone can break through that storm — and, to be sure, it is a strong one — it’s the 77-year-old Alexander, some observers say.

“If there is somebody who has demonstrated their ability to sort of push something forward once they have their mind set on it, it is Alexander,” said Tamara Hiler, senior policy adviser and higher education campaign manager at Third Way, a moderate-Democratic think tank.

Alexander’s long push to reauthorize the law has focused on limiting the federal footprint: His prop FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) form, a string of papers several feet long containing the 100-plus questions families are required to answer to obtain grants and loans, is familiar to higher ed advocates and the education press corps. So is an oft-referenced 2015 report calling for fewer and simpler rules on colleges.

A key to “getting a result,” as Alexander himself likes to say, will be crafting a bipartisan bill with his Democratic counterpart, Sen. Patty Murray of Washington, as he did with the reauthorization of the country’s K-12 education law in 2015, now the Every Student Succeeds Act.

“The bipartisan sheen” of Alexander and Murray’s partnership “dampened significantly” during the contentious confirmation hearings for Education Secretary Betsy DeVos last year, but their deal this summer on health care reignited hopes they could work together, said Amy Laitinen, director of higher education policy at New America, a progressive think tank.

“I think Sen. Alexander and Sen. Murray are both wired to want to work in a bipartisan way,” Laitinen said.

The HELP Committee has had five bipartisan hearings on the higher ed rewrite since November, four just since the start of the year.

Although there’s agreement on some issues, such as simplifying the financial aid application, Alexander and Murray released very different lists of priorities for a reauthorization.

Alongside regulations on for-profit colleges, the future of income-based student loan repayment programs and loan forgiveness for those who work in public service, for instance, are likely to be flashpoints.

Though a reauthorization bill is still in its early stages in the Senate, it’s further along in the House, where it has so far moved on a decidedly partisan track.

The Education and the Workforce Committee in December passed a GOP bill that eliminated federal teacher training dollars; expanded protections for religious schools that many advocates say could, for example, lead to discrimination against LGBT students; limited the number of loan repayment options; and opened up regulations in a way that authors say promotes innovation in higher ed but others worry could lead to abuse by bad actors.

Democrats attacked the measure as prioritizing “corporate interests” over “student interests” and ending a tradition of bipartisan higher education reauthorizations. A nonpartisan Congressional Research Service report released February 6 found that the bill would eliminate $14.6 billion in student aid over a decade, further fueling Democrats’ ire. Key higher ed groups also oppose the measure.

The House bill, known as the PROSPER Act, “would make higher education less affordable, saddle students with greater debt, and push more students into loan default,” a coalition of liberal higher ed advocacy groups wrote to Congress earlier this month.

Jason Delisle, a resident fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute who advocates aggressively simplifying the current financial aid system, said the House bill was “pretty underwhelming in the kinds of reforms it sought to take on.”

“I would imagine in the interest of bipartisan compromise that the Senate proposal will be even more underwhelming,” he said. “They’ll need to do that in order to get the compromise.”

Alexander’s staff has started sharing some legislative proposals with Murray’s team and hopes to get into “deep conversation soon” on specifics, a staffer said. The goal is to have a bill before the HELP Committee this spring, to maximize the amount of time it could be considered on the Senate floor later this year, an Alexander aide said.

Murray aides previously threw cold water on Alexander’s recent assessment that a bipartisan bill could be written in “the next few weeks,” Politico reported. But at a hearing in mid-February, Murray said she is “confident” the two can work together and “negotiate in good faith” to get to a final bill.

There is no guarantee on floor time, but Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has asked for “substantive policy bills” with bipartisan support — 60 votes being needed to pass legislation in the Senate — and a higher ed reauthorization could fit the bill, the Alexander staffer said.

The Senate education committee began thinking about reauthorization in September 2013, Alexander said at the start of one recent hearing: “It is now time to bring our process to a conclusion and present our recommendations to the full Senate for action.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)