Lake & Gross: Some Charter Schools Use Their Flexibility to Serve Special Ed Kids. Our New Report Shows How More Schools Can Do the Same

For parents of children with disabilities, finding a school where the adults not only care about what your child needs but are capable of providing it can be life-changing.

Over the past 12 months, researchers at the Center on Reinventing Public Education and the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools fanned out across the country. We visited 30 charter schools in 13 states. We interviewed dozens of teachers, administrators and school leaders. We recently published our report on that study.

Along the way, we met students who had worried about bullies but found schools where they felt safe.

We saw students who had been relegated to the margins of other schools but now felt like they could be stars — like a young woman who was accompanied by an aide throughout the day and took on the lead role in a drama class production.

And we learned about students who, for the first time, had found environments that supported their learning. As a parent at one of the more structured schools we visited told us: “I started seeing the benefits right away. [My son] wasn’t coming home stressed and worried about the next day … my son is excited because he’s able to achieve not just better grades, but he feels that he’s actually learning.”

These stories of changed lives did not happen by chance. And they did not emerge from the isolated efforts of a special education department. Our study found that effective education of students with disabilities must be a schoolwide endeavor.

In the most promising schools we studied, leaders committed to meeting every student’s individual needs. Teachers blurred the lines between special and general education, and they worked together to solve problems. Parents were full partners in setting learning goals for their children.

In this way, our latest study builds on ideas we at CRPE have developed for 26 years. Charter schools have the flexibility to create coherent organizations that do not trap special education in an isolated silo.

They can hire staff that share their leaders’ commitment to educating students with disabilities effectively, in the same classrooms as their peers. They can elevate the role of parents, who have chosen to enroll their children, to serve as full partners in the education of students with disabilities.

For nearly 30 years, the charter school movement has used these advantages to raise expectations for low-income children of color and committed to helping them reach college at the same rates as their more affluent peers.

More recently, as they have found their graduates sometimes struggling to complete college, some charter school management organizations have launched high-profile efforts to ensure that their alumni earn degrees.

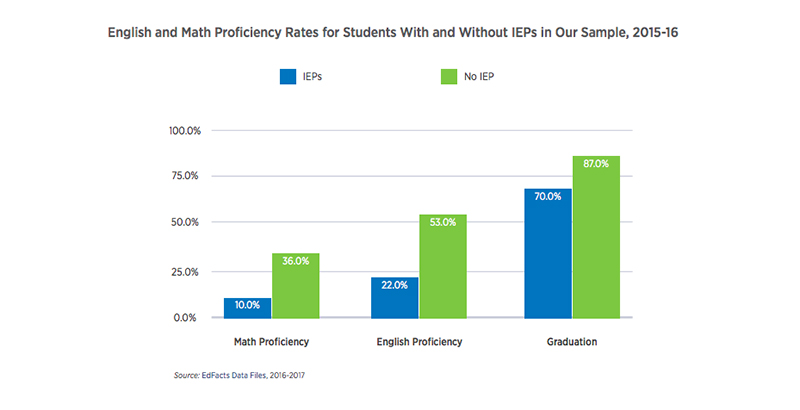

We believe more charter schools must similarly rise to the challenge of closing an achievement gap that does not get the attention it deserves: the gap between students with disabilities and those without disabilities.

Right now, only about 20 percent of students with disabilities score proficient on state assessments. Fewer than 70 percent earn a high school diploma in four years. That’s despite the belief among researchers that 85 to 90 percent of students with disabilities should be capable of mastering grade-level content if they receive the right accommodations.

System-level changes will be necessary to close this gap.

Oversight must focus more on outcomes. The charter school authorizers in our study too often focused on compliance in special education rather than on student results. State, federal and local accountability systems must ensure that schools prioritize strong outcomes for students with disabilities.

Talent will be key to pulling this off. Schools in our study often struggled to recruit teachers and leaders who were highly qualified and committed to educating students with disabilities effectively. And general education teachers often lacked access to training in supporting diverse learners in inclusive classrooms.

Improving outcomes for students with disabilities will require stronger training systems and recruitment pipelines. It will also mean ensuring that adequate funding will follow students with disabilities to the school of their choice.

But schools need not wait for ideal policy conditions to begin improving education for students with disabilities. Our research has identified practices that any school can adopt. School leaders can start by making sure that educating students with disabilities to high standards is a schoolwide priority and considered every teacher’s responsibility. Hiring, staff development and evaluations should reinforce that idea. Interventions and supports should be individualized, and parents should be treated as the best experts on their child.

The key to effective education for students with disabilities is, above all, an institutionwide commitment. We found charter schools that have made that commitment. But more should.

Robin Lake is director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell. You can find her on Twitter @RbnLake. Betheny Gross is a senior research analyst and research director at the Center on Reinventing Public Education and affiliate faculty at the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the University of Washington Bothell. She coordinates CRPE’s quantitative research initiatives, including analysis of portfolio districts, charter schools, and emerging teacher evaluation policies.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)