Lake: Are We Personalizing Learning for the Students Who Need It Most?

This essay, part six in an ongoing series, previously appeared at The Lens, the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s blog at the University of Washington Bothell.

Ultimately, this approach may be just as likely to leave some students behind.

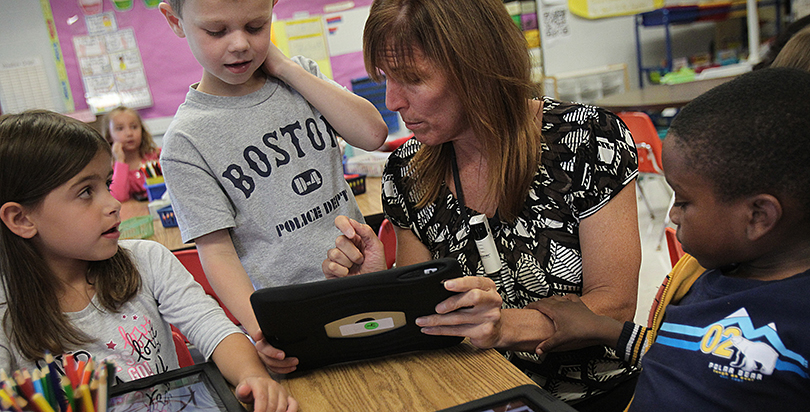

In our visits to PL schools, we’re seeing a move away from traditional lecture-based formats in favor of lively classrooms where students tackle self-designed projects. In some classrooms, students move on a fixed schedule from one learning station to the next. In others, students independently navigate a host of activities on their own timetable.

PL advocates often promote this vision of the “better” classroom. To be sure, these formats give students more input and variety in their learning and, arguably, meaningfully improve on traditional direct instruction. But they don’t work for all students.

We’ve witnessed this problem during our school visits. A student with dyslexia told us he thrives in a classroom that gives students multiple choices over their learning, while another student said she needs more structure. While some students clearly bloom in a loud, active, project-based classroom, a student with autism might be completely overwhelmed by the noise, movement, and lack of clear direction. In schools that ask students to work through online programs and activities, some students report that they love learning online; others say they flourish with textbooks.

Students who need a truly personalized environment may have documented learning needs (like special education, gifted, or English-language-learner status), but often they don’t. These students may simply fall in the normal range of differing learning styles and challenges; they may be “gifted” in some subjects and not in others. At school, they may be marginalized or disaffected, or at risk of becoming so. Children are complex. Some are more complex than others.

There are ways to use personalized learning to reach all students, but as we’ve seen, it takes alert teachers, strong school leadership, and creative thinking.

One middle school we visited stands out as an exception for using myriad PL approaches to try to reach even their most complex learners. The staff created a schoolwide structure that keeps core academic classes small (20 students max). An advisory period gives students connection with an adult who checks on how things are going both academically and socially. As one student said, “Our teachers know us and know what we need.”

Students can move in and out of “gifted” courses as their needs dictate. Students struggling to keep up are taken out of class to review a videotaped lesson with a teacher to ensure they don’t get far behind. Teachers told us about an especially disengaged student who “lit up” on a field trip to a cosmetology school. His teachers worked together to link his learning to his interest, like tying science labs to the chemical reactions that occur when dyeing hair.

Despite efforts like these, the middle school principal worries that they still aren’t effectively reaching a small number of students (he estimates 3 to 5 percent). But the school staff is determined and adaptive, regularly consulting students about ways to improve their experiences, and watching for behaviors that alert them to disengagement.

In one high school we visited, students who struggle to maintain their grades and interest in school can opt into a program that lets them map their pathway to life after high school (be it pursuing post-secondary education or entering the workforce). Each student designs an individual plan — including academics and an apprenticeship or field experience — toward achieving their post-secondary goals. Students get their core instruction from the program’s dedicated staff. The courses are designed with flexibility to let students integrate individualized goals into their curriculum. Students also have the option to supplement their academic program with traditional school courses.

Schools that fully commit to PL must go beyond single-approach solutions to “meeting students where they are.” The most robust array of online programs, the deepest, inquiry-based learning experiences, and the most sophisticated assessments will never erase students’ need for human connection and adaptability. Some students need a wider variety of choices to be served well. Schools might consider offering more structured learning environments for those who need it. They might reach beyond the school building to engage students through learning in the community (apprenticeships and the like), participation in social and recreational activities outside the school, or even partnering with other schools or local colleges to broaden the range of learning experiences.

No school can be expected to be the right fit for everyone. But with flexibility, creativity, and an open door to the community and beyond, schools could get a lot closer to personalized pathways for even the most complex student. Ultimately, personalized learning should be about problem-solving to help every student thrive, not one particular approach to instruction.

In 2015, the Center on Reinventing Public Education kicked off a multi-year, multi-method study of systemic efforts to support schools implementing personalized learning. We’ll produce reports that explore many of these topics in depth as the project progresses, but we want to give educators more immediate feedback. You can follow our “Notes From the Field” series here. Please share your own observations and feedback with us on Twitter: @CRPE_UW, #PersonalizedLearning.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)