Kindergarten’s Overlooked Absenteeism Problem

Missing school isn’t just a high school issue. Parents’ failures make kindergarten another chronic absenteeism peak, sometimes nearing 90%.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

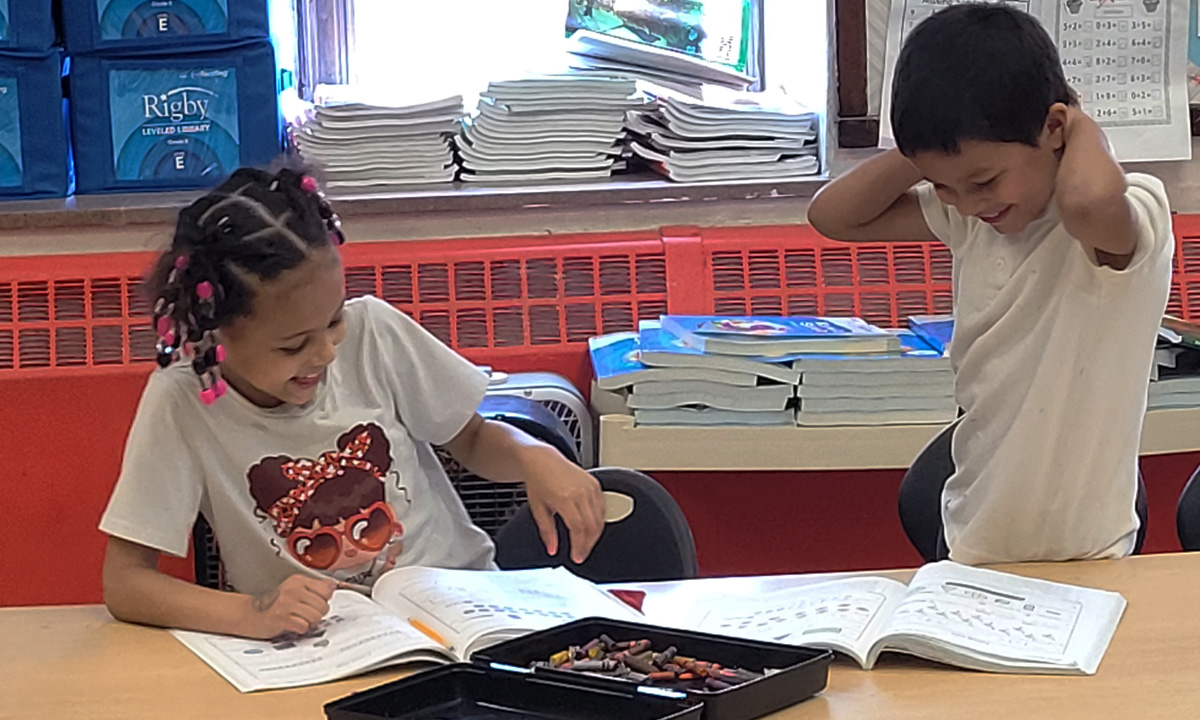

Gabrielle Pobega knows kindergarten is more than just kids coloring, playing and singing songs, so she made sure her daughter made it to kindergarten at Lincoln Park Academy in Cleveland every day.

“They teach you ABCs,” Pobrega said as he picked up her third grader after school. “They teach you how to write. They teach you small little words and it prepares them for first grade.”

But not all parents value kindergarten as much as Pobrega. So many parents treat kindergarten as less important than other grades that it adds up into a major problem — nationally, across Ohio and particularly at Lincoln Park and other high-poverty schools.

Kindergarten has the highest absenteeism problem of any elementary grade in several states, studies have shown. In Ohio, attendance can be so bad that state data show some kindergartens approaching 90% chronic absenteeism.

Though chronic absenteeism — students missing 10 percent or more of school days — is drawing national attention for high school students, there has long been a second, less publicized, peak in absenteeism in kindergarten and sometimes preschool that is also damaging.

Hedy Chang, one of the leading researchers of absenteeism and its effects, said kindergarten absenteeism needs educator’s attention, not just high school absences.

“You really want to worry about both,” said Chang, founder of the nonprofit Attendance Works. “You want to care about your youngest incoming learners, because that’s going to be critical for the long term. What you don’t invest in and address early, you might pay for later.”

Consider: In Ohio, more than a quarter of Ohio kindergarteners missed at least 18 days of school in the 2023-24 school year, state data shows, making kindergarten the highest chronic absenteeism rate of any elementary school grade in the state.

That matches findings by nonprofit FutureEd in March that kindergarteners had the highest chronic absenteeism of any grade in Hawaii and Utah last school year. In all 20 other states FutureEd looked at, Kindergarten had the highest chronic absenteeism rates before 7th grade.

“We see this U-shaped curve,” when charting absenteeism by grade, said Amber Humm Patnode, acting director of Proving Ground, a Harvard based research and absenteeism intervention effort. There is high absenteeism in kindergarten, it improves for several years, and typically rises again in late middle school.

She said there are really two separate absenteeism problems — one for the youngest and one for the oldest students — that need different strategies to fix.

Ohio State University professor Arya Ansari, who specializes in early childhood education, called kindergarten absenteeism “problematic” because missed classes add up over the years.

“Kids who missed school in kindergarten do less well academically in terms of things like counting, letters, word identification, language skills.., they do less well in terms of their executive function skills, and they do less well socially and behaviorally,” Ansari said.

“Days missed in preschool or kindergarten kind of set the stage, or are precursors for future absences,” he added. “So when you’re frequently absent, it kind of begins to have a snowball effect and sets habits that are harder to break later on.”

There’s also another dynamic at play with kindergarten absences: It varies by school, in very dramatic ways.

Though Ohio’s kindergarten chronic absenteeism rate was just above 26% last year, 27 kindergartens had chronic absenteeism triple that rate, coming close to or exceeding 80%. Lincoln Park had the worst rate in the state last year at nearly 90%, with close to 9 out of 10 kindergarteners qualifying as chronically absent.

Adding to the damage, the worst kindergarten absenteeism is happening in places where the students need it most. Ohio’s list of highest absenteeism rates is dominated by schools in, or next to, the state’s biggest or most poor cities — Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, Toledo and Youngstown — where students have performed well below suburban students for years.

In contrast, affluent and higher-performing schools easily have less than 5% kindergarten chronic absenteeism, with several at zero.

Students in the high-poverty schools are not only missing days that could start them on a path to catching up, the absences are holding everyone back even more, Chang said.

“I consider high (absenteeism) at 20%, 30% in a school,” Chang said. “80%? That’s an extremely high level of chronic absence. When schools have really high levels of chronic absence, the churn just makes everything harder. It makes it harder for teachers to teach, set classroom norms and kids to learn.”

Some of why kindergarten absenteeism is so high is easy to understand. For many kids, it’s the first year of school, so kindergartens become superspreader sites for colds, flu and other illnesses kids haven’t been exposed to before. Since chronic absenteeism includes any days missed, even for illness, rates could legitimately spike.

The pandemic added a twist to that, said Robert Balfanz, a Johns Hopkins University professor and another leader in absenteeism research.

“It used to be that parents got guidance (that) If your kid just had sniffles, you could send them to school,” Balfanz said. “Then, coming out of the pandemic, parents got the message… perhaps overload, perhaps not…that should you have any sign of illness, you could have COVID. That’s another factor.”

Just as important: Only 17 states required students to attend kindergarten as of 2023, according to the Education Commission of the States. That easily leads parents to consider it optional and for school to really start in first grade.

Then there’s kindergartners’ need for parents or siblings to take them to school or to their bus stop. If school and work schedules don’t align, or if a sibling’s school is different, kindergarten falls lower on the priority list.

“A kindergartener not coming to school is not necessarily the kindergartner saying, ‘I’m not going to school today,’ ” said Jessica Horowitz-Moore, chief of student and academic supports for the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce. “That has to do a lot with the parents.”

Parents oftentimes don’t appreciate how fast absences add up. Another parent picking up children at Lincoln Park was a perfect example. That father said his child only missed school “a couple times a month” when in kindergarten. But twice a month is 10% of the 20 school days in a month (Four weeks of five days each) which is right on pace for chronic absenteeism.

Some of the kindergartens in Ohio with the worst absenteeism in 2023-24 were failing in many other ways too: Two charter elementary schools with kindergarten chronic absenteeism over 87% closed before school began this academic year. Some, including the Stepstone Academy charter school in Cleveland, did not respond to multiple messages from The 74.

Lincoln Park, with the worst kindergarten absenteeism problem in the state, is part of the ACCEL charter schools, a fast-growing multi-state charter network, that had five of Ohio’s 10-worst kindergartens for chronic absenteeism.

Representatives of the network said the schools are often in high poverty neighborhoods with families that move frequently, which disrupts attendance. Students often don’t have reliable transportation, they said, and Ohio’s charter schools have less money to put toward attendance issues than districts.

Lincoln Park school leaders say they’re trying to improve attendance and academic performance. Both the school’s principal and kindergarten teacher are new this year and interim Principal Erika Vogtsberger said she expects the preschool attendance rate to go up from 74% last year to about 80% this school year.

She said fewer families are moving during this school year than last, and more than 90% of Lincoln Park’s students have signed up to return, bringing stability she thinks will help attendance.

The school has also been trying for a few years to encourage attendance. It has early morning and afterschool sessions so working parents can drop children off at 6:30 am and pick them up as late as 5:30 pm. It holds special events like pancake breakfasts for families to encourage attendance and gives classrooms with 90 percent attendance for five days a chance to spin a wheel for rewards like pizza parties or a chance to wear pajamas to school for a day.

But even at 90% goal to earn prizes still leaves 10% of students absent racking up days toward chronic absenteeism.

“We have to make it attainable,” Vogtsberger said. “If I had it at 95%, the kids who are here without missing a day are going to get discouraged because… we do have a small cluster of people who are out pretty regularly.”

“Nobody would get it,” added Sherree Dillions, a regional superintendent for ACCEL. “At least, with the 90%, peer to peer pressure is a big piece. You say ‘You better come … You better come tomorrow, because we want that pizza party’, or we want whatever … Because the kid wants the prize.”

Voghtsberger said she also does not want to punish students, either, because their parents aren’t doing what they need to do.

“No matter how bad some students want to be at school, if their parents are not getting up in the morning and bringing them, they cannot get to school, and… that’s not their fault.” she said.

School officials also said parents are a problem beyond not bringing children to school. Parents, they said, are often abusive when called or visited to check on students and have sometimes threatened school officials with guns or dogs. Ohio has also moved away from taking action against students or parents for truancy, so parents face no penalty for keeping students home, as they do in other states, including Indiana, West Virginia and Iowa.

“If I had my way, parents would be held accountable across the board,” Dillions said.

The Toledo school district, whose Sherman elementary school has the worst absenteeism of any school district kindergarten in Ohio, also saw parents push back when the school called or visited about students skipping school. The district decided in 2017 to pay for well-known people in neighborhoods, like football coaches or local volunteers, to serve as “attendance champions” to talk to parents instead of school officials.

“(They) go out to the homes,” Baker said. “They complete home visits. They work with the families to remove barriers to attendance. They’re in the buildings every day, building relationships with students, removing barriers on that end as well.”

“They are not truancy officers,” Baker stressed. “They are not to issue any punishment. That’s not their thing. This is about, ‘How can I help get Johnny back into school?”

The champions have reduced some of the tension between schools and parents, she said.

Baker has seen better attendance this year, so she expects kindergarten chronic absenteeism there to fall from about 87% to 77% — still about triple the statewide rate.

There are some reasons for optimism across Ohio and nationally. Absenteeism at all grades, including kindergarten, is improving yearly since the end of the pandemic everywhere.

Baker said, though, that kindergarten may need to be more of a priority.

“We’re going to have to really hit preschool and kindergarten a little bit harder with our interventions that we are setting up,” she said. “We have been very much focused on high school. But I think for us as a district … we really have to continue to hit this hard across the board.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)