Journalist Natasha Alford on Race, Identity & Her New Memoir, ‘American Negra’

'I wanted to unmask the image of the successful, inner-city poster child with this book,' CNN political analyst and TheGrio anchor and VP tells The 74

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated, March 6

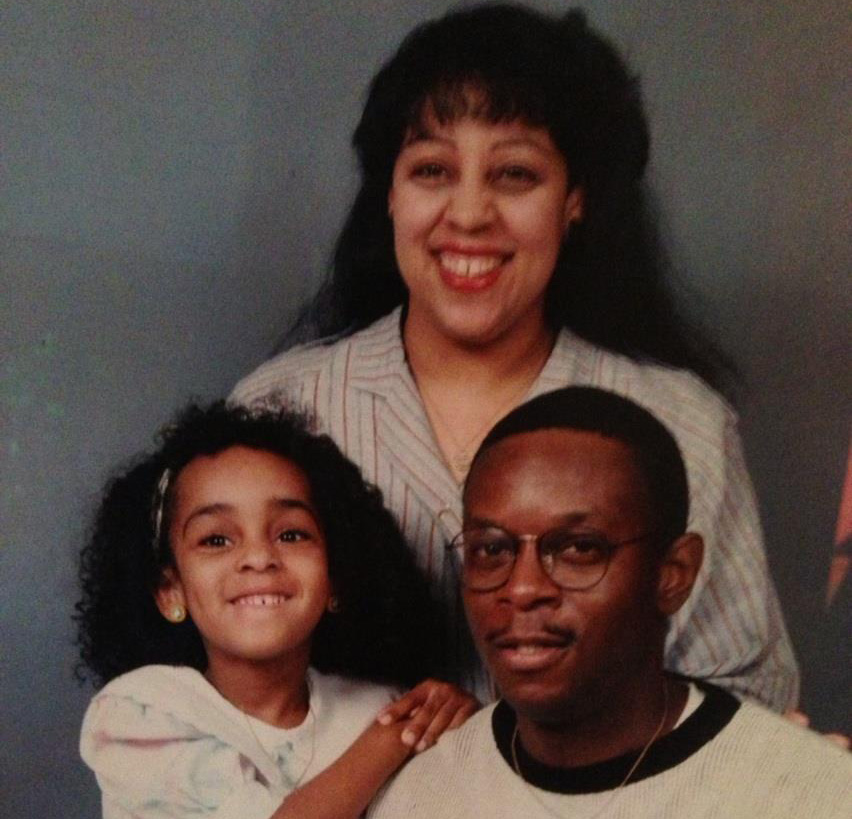

In Natasha Sonia Alford’s newly released memoir, American Negra, she describes an early childhood memory of being the new kid at school: “What are you?” another student asked. “I’m Puerto Rican and Black,” she responded, noting these were “the only words I had at the time to explain my identity in terms that made sense.”

“Language mattered,” she writes, “and yet at this age no one had prepared us to explain who we were accurately.” Her memoir does just that: it is an exploration of her intersecting identities and an explanation of their impact on her experiences as a student, teacher, hedge fund management associate and journalist.

Alford’s story begins with her childhood in Syracuse, New York, where she excelled academically and was ultimately selected as one of three college-bound students to be profiled by the local newspaper during her junior year. After receiving acceptance letters from a number of selective schools, including Howard University, Alford enrolled at Harvard.

Despite her successes and on-paper credentials, as she calls them, Alford struggled at first to find her passion and her place as the pressures of perfectionism wore on her.

While American Negra is a study of Alford’s personal identities, it is also an analysis of American society more broadly, with a particular focus on our education system. She writes about the mantra she was taught that for kids of color in the U.S., education is the path out of marginalization. She encourages readers, though, to expand their understanding of this idea: too often, she argues, students are told that in order to be successful in school they must erase parts of themselves and conform.

“I wanted to unmask the image of the successful, inner-city poster child with this book,” Alford told The 74. “The point is that that pressure to be ‘twice as good,’ if you bring up a child in that culture and with that rhetoric, they may still struggle years from now — even after they’ve left school — to feel like they are worthy and that they are good enough.”

Years after graduating from Harvard, the 37-year-old, former Teach for America alum said she finally felt ready to take a risk and pursue a career in media. Alford, who got her master’s at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism and who freelanced for The 74 early in her career, now serves as the vice president of digital content and an anchor at TheGrio, where she leads a national team reporting on critical issues facing Black communities. She is also a CNN political analyst and the recipient of numerous awards including “Emerging Journalist of the Year” in 2018 by the National Association of Black Journalists.

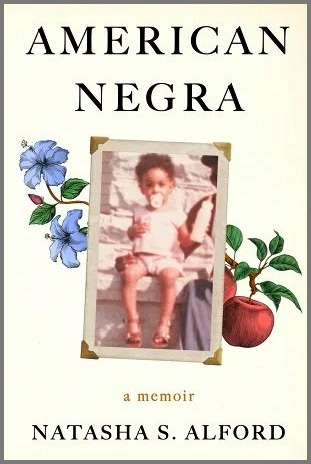

American Negra, published by HarperCollins on Feb. 27, was named a “Best (and Most Anticipated) Nonfiction Book of 2024” by Elle and the audio version hit No. 19 on Amazon’s bestseller list for Black and African-American books. The 74’s Amanda Geduld chatted with Alford about her book, education policy and solutions journalism.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: I want to start with a little bit of context. Can you explain to our readers how you selected the title for your book, American Negra?

“American Negra” is a phrase that describes what it’s like to live at the intersection of two worlds. I wanted to paint a portrait of an American experience that we don’t see often portrayed in the mainstream: being an African American and being a Latina — Puerto Rican specifically. The term “negra” just means a Black woman. If it’s “negro” it means a Black man. When you are in Latino cultures, it is not uncommon for somebody to refer to you as a “negra.” It is often a term of endearment, but it can also be used as an insult. But the point is, ultimately, that they are centering your race and your identity.

What makes it so interesting is that often in Latino cultures, we hear about color blindness and we hear about racial democracy. There’s an assumption that because many Latinos are people of color, there’s not really an issue with race — that race is something that is sort of a U.S. obsession. And so there’s a bit of a contradiction in that obviously: a culture that doesn’t really see itself focused on race to identify people by their race. I wanted to highlight that experience, while also making it clear that my experience was one that is based in America. I’m an upstate girl — grew up in Syracuse, New York — and so my experience of being Black and Latina is very much influenced by the United States and all of our recent politics and all of our histories.

And then finally, I think it’s also a declaration. It’s an embracing of the term because for some people to be called “negra,” or to be identified that way, is a bit of an insult. They don’t want to be called Black. But for me, I’m really centering my Black identity to say that no matter where I go, I’m a Black woman. It shapes my experience. I’m proud of it.

At each step of the way, young people are shedding parts of themselves or feel that they’re forced to. In the end, they may not recognize themselves. They may have succeeded on paper, but they’ve lost themselves in the process.

Natasha Alford

So much of your book comes back to the themes of education and opportunity. What inspired you to tell the story in this way — with such a heavy focus on the education system — and can you talk about the ways in which your Black and Puerto Rican identities shaped this journey?

That is exactly why there’s an apple on the front cover of the book. That was very much intentional, because this is an education story as much as it is a story about identity. The reason why is because for so many communities of color — communities that are marginalized in the United States — education is our path out of that marginalization. At least that’s the message that we are told from the time that we are children. And that was the message that my parents imparted to me: that I came from two peoples who had been discriminated against in this country at various points in time throughout history, but education was something that no one could take from me.

What you see in this book is the pursuit of education, but also the pursuit of authentic self. I think too often when we talk about education and young people, it’s framed through this lens of conformity: you go to school, you have to assume a different identity, you have to speak a certain way, there are certain careers that are so-called successful. At each step of the way, young people are shedding parts of themselves or feel that they’re forced to. In the end, they may not recognize themselves. They may have succeeded on paper, but they’ve lost themselves in the process.

I wanted to disrupt the education narrative that ends with someone getting into the Ivy League or getting into college and that being the end. And say no, actually, that’s when things just get started. The success is not just getting into this institution or conforming to this institution, but it is what you do with [it]. That’s the power of education …

In terms of your own path to becoming an educator, your senior year at Harvard, when you were initially debating your career in education, you write in your book about this fear that people might say, “You went to Harvard to become a teacher? Shouldn’t you be doing better than that?” I’m wondering where you think this devaluation of educators comes from and what we can do to combat it.

There’s this really great piece … about how high achievers learn to not become teachers. It explains essentially that we have created a culture in which young people pick up messages about what careers are valued and which ones are not. In terms of where this comes from, I can only assume that there’s a gendered dynamic to this.

There is an element of sexism that has made its way into education and the fact that the majority of teachers are women, and women are not always paid what they deserve — we are often behind in terms of our male counterparts and many more are behind when you look at the different segments of women by race. So we are a society that gives teachers lip service, but doesn’t actually back it up with a financial investment in teachers and education more broadly.

I actually don’t blame young people for seeing that. I don’t think that young people should have to be martyrs, frankly, especially young people who may be coming from working-class families themselves — may be coming out of broken educational systems. To go back and teach I don’t think they should have to struggle. From my short time in the education policy space and just in education, my takeaway was that we have a pipeline problem in terms of recruiting generally, but that in order to change education, you’re going to have to pay the talent — you’re going to have to pay them, you’re going to have to nurture them, and that it shouldn’t be an industry that you’re going into to make a sacrifice … This is something where we’re going to make the investment and see the results or not make the investment and the overall system will continue to struggle …

How can we get teachers to persist in the classroom when they’re up against challenges like the ones that you write about, like chronic absenteeism or eighth graders reading at a first-grade reading level?

… I think what maybe would’ve kept me in the classroom was just having realistic expectations about what I could do in two years. Sometimes when teachers come in, they’re idealistic and they’re not necessarily ready for how long these problems have been brewing. If a student has not been supported academically from kindergarten, and you get them in fifth grade, there has to be some level-setting about what you can do.

And so one critique I have of the short-term teaching programs is just with the optimism and the accountability and the expectation of making change. Sometimes there’s also unrealistic pressure put on a new teacher about what they can accomplish in one or two years, and that can be really deflating. If that teacher comes in hoping for the best, working really hard, going above and beyond, and they don’t see the “results” that are so valued by the people who are counting the numbers and counting the test scores, that makes them feel like a failure. When in fact, it takes much longer to build — whether it’s building school culture, establishing yourself within the school community, or just becoming the teacher that you truly can be …

You recently tweeted about Nikki Haley’s “revisionist history” and the general idea within the Republican Party of color blindness. You were on CNN talking about why those narratives are so harmful, and I’m wondering if you can comment a little bit more on that in terms of how this plays out in the educational landscape.

She’s used the talking point many times: that if we tell children America was once a racist country, that somehow they will feel disempowered, and that they will feel like victims, and that they will have no incentive to try. That couldn’t be further from the truth. We have examples every day of people who were fully aware of America’s racist history, and who are strong in spite of that, who invested in this country in spite of that, who served this country in the military and in schools and universities, in spite of what they faced …

We have to contend with this history because it’s ours. We have to own it. And that’s how we become a better county with each passing year, with each passing decade. But to ignore it is to handicap our children. It can leave them without context or understanding of what they’re looking at. What it does, then, [is lead to them] blaming themselves, believing that they’re inferior, thinking that something is wrong with them, and not necessarily wrong with the systems that produce many of the inequalities that we see today.

So I completely differ from Nikki Haley in terms of my approach to history, and also just my general acceptance of America’s past. But I think it’s instructive and yet another reason why teachers are on the front lines of these culture wars around what is true and what is not. I give my deepest respect to all the history teachers and all the social studies teachers, because they’re doing some serious work right now that is important for raising a conscious generation who will go forth empowered to make change for the better.

You also recently wrote about race in higher education specifically around the former president of Harvard, Claudine Gay, stepping down. And this line really stuck out to me from your op-ed: “With a new generation of Black students and young people looking to us adults for lessons from this moment, perhaps they are better served to know the truth: that even being ‘twice as good’ won’t always protect you from people who need your failure to justify their blind rage.” I’m wondering if you can expand a little bit more on how you experienced Gay’s stepping down and the vitriol that she received, especially as an alum of Harvard.

It became apparent right away that the attacks on Dr. Claudine Gay were about more than her testimony on the Hill. We’ve essentially forgotten about the third president who testified. It just went to show that this was always about more than the initial conversation of anti-semitism. What was really disheartening was that she became a punching bag for all of these critics’ anger and rage and a sense of frustration with what they feel is a loss. What they feel is that Black people’s advancement is somehow their loss, even though we’re all in this together. We’re all living and creating community and shaping this society together. Somehow they see it as a zero sum game …

I wanted to unmask the image of the successful, inner-city poster child with this book. The point is that that pressure to be “twice as good,” if you bring up a child in that culture, and with that rhetoric, they may still struggle years from now — even after they’ve left school — to feel like they are worthy and that they are good enough.

I read an article, I think it’s called “Contingencies of Self-Worth,” and the biggest lesson of that piece is that our own self worth can’t be contingent upon grades or upon getting into a certain school. We have to shift the way that we’re teaching young people about their value. And so “twice as good” is a survival strategy, but it’s not necessarily a strategy to thrive. I hope that my story — by being honest about many of the struggles that I’ve had despite having acquired certain credentials on paper — [encourages] others to talk about some of their struggles as well, and that we can cultivate a new generation that will be kinder to themselves and also accepting of the fullness of their humanity.

As a high schooler, you were followed by the local newspaper for all of your accomplishments. What kind of impact did that have to be so perceived at all times? It was because you were a role model and accomplishing so much, but I wonder what kind of narrative that instills in a young person about what they need to do to be successful.

Right. It was certainly a privilege, and I am grateful for the coverage that the local paper gave and appreciate that they wanted to show a young person of color from the city doing positive things. However, that also created a sense that failure was not an option. Making mistakes was not OK. And it inhibited me in ways. There were certain things that I wanted to try or do that I was afraid to do because I couldn’t guarantee my success. And that is not a way to go through life. You have to make mistakes, you have to experiment. You have to fully spread your wings in order to discover yourself and so really, I don’t spread my wings fully until I’m long gone from college.

Five years after that I truly am honest with myself about what I’ve always wanted to do, and that was journalism and media. And I’ve made peace with, “OK, this might not work out, but I have to give it a try. I have to know if this is what I’m supposed to be doing.” It took much longer because of that perfectionist mindset that wouldn’t give me the freedom to try right out of school.

My story is my story. I’m happy still. I think my life still worked out. I ended up where I wanted to be. I still feel blessed. But maybe someone else will be able to get to their destination a little bit sooner if they’re able to let go of some of that perfectionist weight that can keep you down.

As a former educator and now a journalist, what are education journalists getting right and wrong today? And how can we strengthen our coverage and make sure that we’re combating some of these problematic narratives that have become so ingrained over the years?

I know that journalists are working hard, and it’s not always easy. We have deadlines and fewer and fewer resources. I know many of us are doing the best that we can. But I would encourage us to move towards solutions journalism. We are dealing with a public that is weary. They’ve been hearing about problems nonstop. And it’s our job to also provide examples of what is working. Who’s getting it right. And not in a superficial way of “this overachiever managed to do X, Y and Z.” But what risks were taken? What experimentation is happening that’s really inspiring?

I think it’s our job to highlight those things and also highlight diverse examples of this. Be open to information. Be open to inspiration coming from unexpected places and give people a reason to hope. That is our job as much as it is to point out what is not working. Because I think people who are living it know that a lot of this is not working. So I think that we can do that work to point them towards potential solutions and then hopefully people are inspired to go out and enact it at a grander scale.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)