Jones & Lesaux: Amid Pandemic Disruptions — & Despite Political Attacks — it’s Time to Focus on Children’s Social and Emotional Well-Being

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

To succeed in the classroom, children must be able to cooperate with other students and their teachers, focus their attention, control impulsive behaviors and manage their emotions so they can concentrate on the tasks at hand. They need to have a sense of belonging and purpose, be able to plan and set goals, and persevere through challenges. In other words, they need social and emotional skills. Yet the teaching of social and emotional learning in schools has recently come under attack, and at the worst possible time.

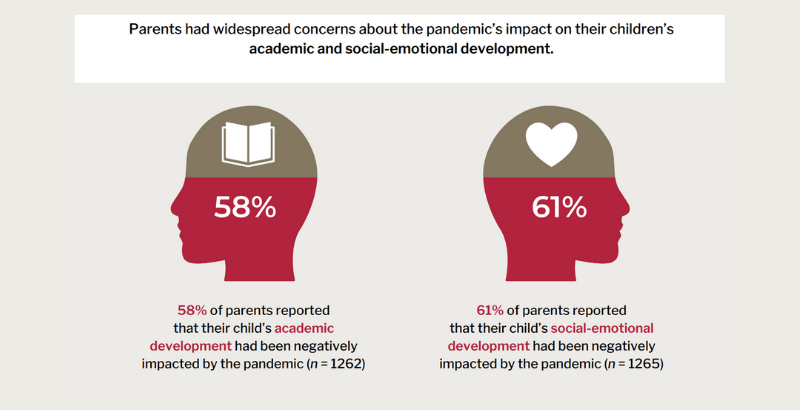

The COVID-19 pandemic has put children’s essential social-emotional skills at risk. The surgeon general and others have warned of an alarming increase in children’s mental health and behavioral problems. We’ve seen the same thing in data from our Early Learning Study at Harvard (ELS@H), a statewide study of about 5,000 young Massachusetts children and their teachers and caregivers whom we’ve been following since before the pandemic began. Teachers told us that they’ve seen sharp increases in behaviors like temper tantrums and trouble switching from one activity to another. Parents said that after a year or more of remote learning, their children struggled to interact positively with other kids. In fact, the parents we surveyed were more worried about the pandemic’s impact on their children’s social-emotional development than they were about its effects on academic skills.

Because group settings are great places for children to learn and practice social and emotional skills, preschools and elementary schools have been places for adults to teach and model them for many years. Today, to bolster children’s academic learning in the wake of the pandemic’s disruptions, educators need support for SEL in the classroom and curriculum.

Until very recently, SEL was uncontroversial, because children who are able to cooperate, focus and manage their emotions and impulses do better in school. This is true for kids from all backgrounds — wealthy and poor, urban and rural, Black and white. Countless academic papers, reports and news stories— even a national commission comprising parents, young people, policymakers, educators and researchers — have lauded SEL’s potential to drive and support learning. Recognizing how SEL programs contribute to children’s academic success and overall well-being, education departments and school systems in red and blue states alike have adopted and championed social and emotional learning and teaching, and in many cases have set standards for children’s development in this area.

But that’s changed almost overnight. Driven by a distorted and misinformed representation of teaching SEL, groups of parents in district after district have angrily protested at school board meetings. School board candidates have run on explicit promises to remove SEL from the curriculum. Conservative groups have disseminated forms that parents can use to ask that their children be exempted from SEL lessons. Legislators have introduced bills that would ban it from their states’ classrooms. And red-state education leaders, though they know SEL’s benefits well, have backed away from plans to bolster it in their schools, fearing a backlash.

It’s hard to know whether these attacks are cynical or sincere, though they may well be some of both. Certainly, demonization of SEL seems to be part of a push to use parents’ pandemic-driven fears about their children’s education as a wedge to divide Americans along political lines.

Despite the recent and somewhat bizarre attacks, parents, along with educators and policymakers, have long understood and embraced SEL, sometimes referring to it as life skills or positive youth development. Unquestionably, when parents are asked what they value for their child’s education, they mention social and emotional skills such as setting goals, learning about and managing emotions, and getting along with others. This is true for an overwhelming majority of parents, and across all political lines.

They’re right — these are the skills children need to get through these times and rebound academically, and schools are a great place to learn them. Now isn’t the time for political, superficial or unfounded arguments. SEL isn’t a distraction from academics, it’s an essential underpinning of learning across the curriculum, as well as mental health and well-being. Eliminating SEL programs would do nothing but further hurt today’s children — especially the youngest children, and especially now.

Stephanie Jones is the Gerald S. Lesser Professor in Early Childhood Development. Nonie Lesaux is the Roy Edward Larsen Professor of Education and Human Development at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Together, they co-direct the Saul Zaentz Early Education Initiative at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)