‘Jim Crow Debt’: Black Student Loan Borrowers Say Staggering Repayment Prevents them from Affording Food, Rent, Health Care, Homes, Retirement

By Marianna McMurdock | November 22, 2021

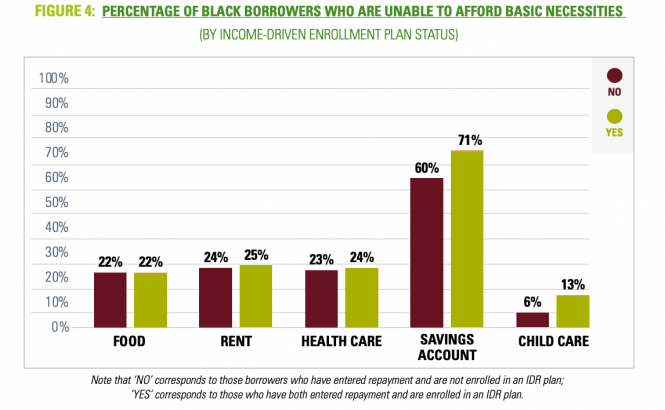

Black student loan borrowers face staggering repayment plans that stretch on for decades, making it impossible to afford basic necessities like rent, food and health care, according to a new report.

Loans were repeatedly described as a “lifetime sentence” in interviews with 100 degree holders. For those enrolled in income-driven enrollment plans that stretch on for upwards of 20 years, growing balances are “shackles on their ankle,” and “like Jim Crow,” with virtually no chance of total repayment.

Health scares, job insecurity and refinancing homes or vehicles with high debt-to-income ratios have derailed borrowers’ futures and compounded stress, according to the Education Trust report, “Jim Crow Debt: How Black Borrowers Experience Student Loans”. Many feared the only way out from under would be, “taking it to my grave” or “when I die.”

Many of the 1,300 Black student loan borrowers surveyed by the Education Trust are unable to access economic freedom because of their debt. An overwhelming majority cannot sustain savings, according to the advocacy nonprofit.

The majority, 66 percent, regret taking loans in the first place. Only 32 borrowers in income-driven plans — of 2 million who’ve made payments for over 20 years — have ever had loans cancelled.

It’s been well-documented that Black students — who because of systemic racism, are unable to tap into generational wealth — borrow more and repay at slower rates than peers of other races.

This report is the first national look at the day-day toll that debt has on Black families.

It’s also the first to explore borrower-identified policy solutions, like doubling federal Pell Grants, lower interest rates and realistic debt cancellation.

“This is not about individuals making the wrong choices, because they didn’t have good choices to make,” said Victoria Jackson, Education Trust’s federal and state policy lead on college affordability.

Attempting to get loans forgiven through existing programs is also nearly impossible, graduates say.

One borrower, named Georgia for anonymity, took out $24,000 in 1990 and owes $125,000 today.

“I have worked at a nonprofit for 27 years and have tried to work with my multiple loan servicers to get public service forgiveness. I only get the runaround,” said Georgia, who like 72 percent of those surveyed by the Education Trust, is enrolled in an income-driven plan.

“I tried the Department of Education, my Congress members,” she said. “I am 62 years old and do not know how I will retire.”

Researcher and co-author Jailil Mustaffa Bishop said student loan policy debates are always “based on Black people’s data, but not really involving actual Black people. We weren’t hearing how Black borrowers were framing their problems and expressing the solution.”

Whether by coincidence or fate, the timing of their project “collided” with national discussions around debt cancellation and the urgent need to reform college affordability.

No ‘good choices’: How policy enables a lifetime of debt

Like many other borrowers, Georgia, struggling to retire, said she received confusing information as to which loans qualified for public service forgiveness or income-driven-repayment.

With lower monthly payments and cancellation promised after about 25 years, she chose an IDR plan. Thirty-one years later, she has not had any student loans forgiven and her balance has compounded.

Her experience mirrors that of 2 million borrowers who’ve paid for decades without relief. A mountain of red tape and convoluted paperwork stands to keep borrowers in “lifetime sentences.”

Intended as a temporary strategy to help borrowers pay down balances post-college, IDR plans rolled out in 1995. Borrowers pay smaller balances, based on income, and debt spreads out over 20-25 years as opposed to the original 10.

Once borrowers are back on track, perhaps with higher paying career moves years after graduating, they can go back to standard payment plans.

But getting “back on track” to paying off the original loan has proven impossible, particularly for Black borrowers, with mounting costs of living, racial wealth gaps and stagnant wages.

“[An IDR plan] provides immediate relief, but it doesn’t offer a solution to borrowers who are looking at a potential lifetime death sentence, as many Black borrowers in our study described … It just offers a way for them to kind of manage that debt, but not really a solution to pay it off,” co-author Bishop said.

Today, IDR is touted as the primary solution to the student debt crisis, over cancellation or forgiveness.

Yet those in IDR plans rarely see balances go down, only mount with interest. The high debts harm borrowers’ chances of buying homes, renting apartments or accessing credit lines — even more so than those with typical student loan plans.

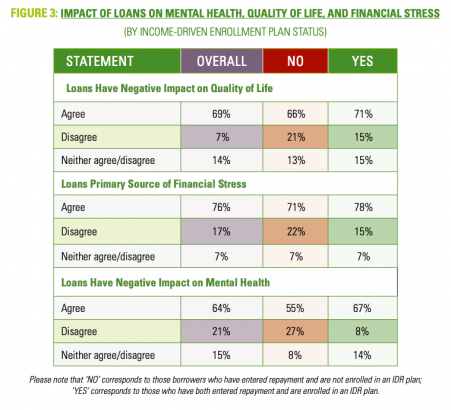

“Those in the study that were actually enrolled in an IDR plan … more frequently reported that loans were a source of financial stress. They had a negative impact on their overall mental health, as well as a negative impact on their quality of life,” Education Trust researcher and report co-author Jonathan Davis said.

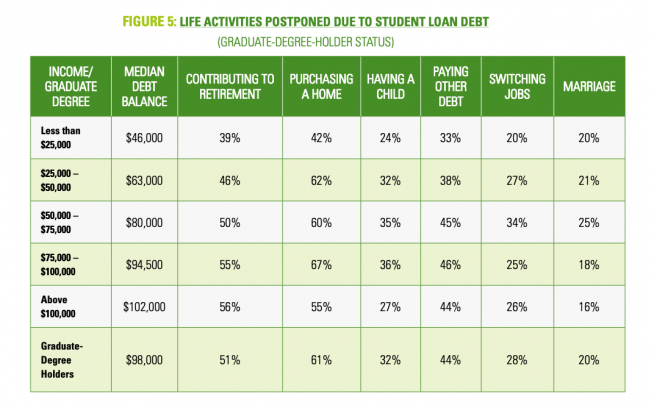

About a third of graduates surveyed even postponed having a child because of their student loan debt; about half have put off retirement savings.

Even more striking, 67 percent of those earning $75-100,000 delayed buying a home because of their student loan debt. The number is nearly just as high, 61 percent, for those with graduate degrees, in theory, better positioned in their careers.

Chronicling the human toll behind current federal loan policies, the report makes the case for race-conscious reform.

The future of loan policy, as told by borrowers

“I mean, realistically, I think the [student loan] system is working exactly as we expect it to … no one’s surprised that we somehow built a financial aid process and policy and set that up to only consider your annual salary, as if [Black people] all have the same net assets,” one borrower said.

First and foremost among the solutions, with 80 percent surveyed in support, is wide scale debt cancellation.

Researchers told The 74 that when it came time for cancellation through IDR plans or public service loan forgiveness — which only 2 percent of borrowers have ever successfully accessed — Black borrowers were often disqualified because of technicalities.

Jalil Mustaffa Bishop said the administrative process is intentionally difficult, similar to bankruptcy filing.

“There’s a lot of clauses, really it means that a borrower has one misstep that may derail their whole repayment strategy. And that’s also a part of the design … that was built into student loans to make it really hard to get from under this debt. We should see that as a decision that was made, not just kind of an accident that came into being.”

Common proposals cap forgiveness at $10,000 or suggest “means-testing”, or limiting who is eligible, for example, to those making under $100,000. Yet Black graduates experience greater wealth gaps and higher debt than any of their peers.

Limits or caps on forgiveness would “disproportionately exclude Black borrowers.” They’re more likely to have high balances and take on graduate school debt to “hedge against discrimination” in the workforce, the report cautions. They’re also least likely to amass wealth long term because of systemic racism.

Four years after graduation, Black graduates typically owe twice as much as white graduates — a result of racial discrimination in hiring and wages, and needing more in loans because of generational wealth gaps.

Borrowers and researchers also advocate for doubling the federal Pell Grant, currently capped at $6,495 annually. The increase would entirely eliminate the need for federal student loans for about 75 percent of families living in poverty, and 85 percent of low-income Black families.

For years, funding declines drove up university tuition as wages stayed stagnant. Accordingly, fewer and fewer families can afford higher education.

And “the purchasing power of the Pell Grant, the nation’s most important college grant, has declined significantly,” Education Trust policy expert Jackson said.

The National Study on Black Student Loans research team will roll out more reports on specific populations and issues within the student debt crisis, like Black women and parent borrowers. They’re also in the process of building a data hub for students, policymakers and advocates to explore research, solutions and students’ lived experiences.

Black borrowers’ experiences also point to a need for transparent loan counseling, particularly when facing income-driven plans that compound for decades with lower monthly payments.

“We still found that those in plans — that by design are supposed to help you better manage your loan repayments — are unable to afford basic necessities like food, rent, healthcare, contributing to saving, childcare… We want to humanize that. While these plans by intent were designed to do one thing for black borrowers in our study, they have not yet proved to meet that intention,” report co-author Jonathan Davis said.

Disclosure: Marianna McMurdock was an intern at the Education Trust-West in the summer of 2020.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter