Jeffries: It’s Not About ‘Bad’ Teachers or Unions. It’s About Better Preparing ALL Teachers for the Classroom

After months of all but ignoring the urgent issue of education during this year’s presidential campaign, CNN’s Anderson Cooper finally came right out at Sunday night’s Democratic Debate to ask Secretary Clinton: “Do unions protect bad teachers?”

To which Clinton responded, “We need to eliminate that criticism.”

The Democrats for Education Reform agree that ensuring we have quality teachers in the classroom is essential. And what's one of the best ways to do that? By addressing the root causes that are leaving too many of our students without the great teachers they deserve.

Why not try to stop "bad," or rather ineffective, teachers before they start? Do a better job training new teachers, raise the bar for licensure, and focus the accountability bull’s-eye where it most belongs — on grossly failing schools of education, and alternative teacher preparation programs, rather than the individual teachers those schools and programs under serve.

(Related: Campbell Brown — Hidden In Plain Sight: Education and the 2016 Campaign)

Teachers learn how to teach their first year on the job. But that approach isn’t fair to new teachers, and it’s a disaster for black, Latino, and low-income children who disproportionately encounter a stream of rookie teachers year after year, grade after grade.

We know that teacher quality is the single biggest in-school indicator of whether a student will be successful in pursuing their education. Teaching is a tough profession — and like any other, it’s one that requires meaningful training, preparation and ongoing support.

About two-thirds of superintendents, principals, and teachers themselves say teachers graduate from teacher preparation programs “unprepared for classroom realities.”

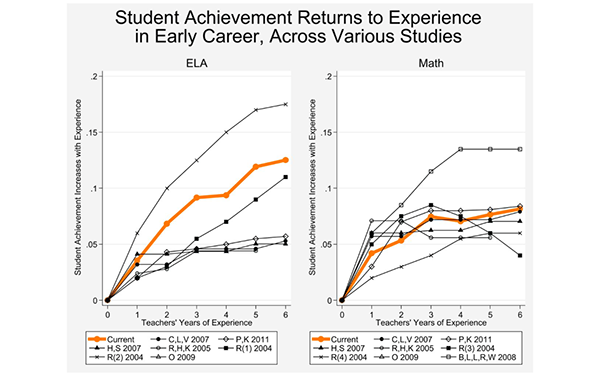

Data on student achievement backs up the perception. There is a sharp increase in teacher effectiveness during their second year in the classroom as opposed to year one, a smaller improvement in year three, and then performance levels out for a number of years.

But year one can be devastating. We could train new teachers much better if preparation programs replicated more closely the year one, on-the-job learning experience while prospective teachers are still enrolled in schools of education — rather than retain the current sink-or-swim scenario.

Teacher preparation programs should be based in high-quality clinical experience supplemented by education theory, not the other way around. This is something that might make school of education faculty who have tenure and are used to teaching theory uncomfortable, but our top priority simply has to be outcomes for children whose future is on the line.

(Related: Shavar Jeffries’ Breakthrough: What Newark politics taught him about taking ed reform national)

To be clear, though, better clinical training isn’t going to do enough to prevent ineffective teachers. Schools of education are notoriously easy graders. Paper-and-pencil teacher licensure exams have low standards, are not reflective of the classroom skills teachers need, and lack predictive validity. Teacher licensure exam pass rates are in the high-90s while subsequent K-12 student proficiency levels stagger in the mid-30s.

No teacher should be fully licensed until they pass a live, stand-up-in-a-classroom performance-based new teacher assessment with predictive validity and prove they can substantially raise student achievement.

But the main accountability target should be the alternative route and school of education programs. Deans of schools of education and others in the field will say the same. Stanford University’s Linda Darling Hammond, for example, has said, “About a quarter of teacher education programs are great. About half are good. And about a quarter should just go away.”

Let’s identify the ones that should go away based on multiple measures — failure to train teachers for high need subject areas and populations, failure to place program graduates in teaching jobs and see them retained in the field for which they’re trained, and most importantly, failure to produce new teachers who have more than a minimal positive impact on K-12 student achievement.

Even though low-performing teachers improve markedly after year one in the classroom, the average low-performing new teacher, measured by year one results, never catches up in effectiveness — in years two, three, or four — to the level of effectiveness of a median first-year teacher.

Student achievement returns to teacher early career experience, preliminary results from current study (bold) and various other studies. Results are not directly comparable due to differences in grade level, population, and model specification, but Figure 1 is intended to provide some context for estimated returns to experience across studies for our preliminary results. Current = results for Grade 4 and 5 teachers who began in 2000+ with at least 9 years of experience. (Source: American Educational Research Association)

In other words, teacher preparation programs that consistently produce low performing teachers year one in the classroom also do a disservice over time to K-12 students — again disproportionately black, Latino, and poor children. These programs, be they traditional or alternative route, must improve or lose eligibility to contribute toward the granting of state teacher certification.

Just as we all rightly expect our next president to walk into the Oval Office prepared to lead on day one, our children have the right to expect the same of their teachers when they walk into their classrooms each fall. Every student deserves to have a great teacher who can help them achieve their full potential. That simply won't be possible if the teachers themselves don't receive training that helps improve their performance before they earn their title.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)