Jeffries: Fighting for Educational Equity in Martin Luther King’s Name Means Battling White Supremacy — and Facing the Consequences

Updated April 4

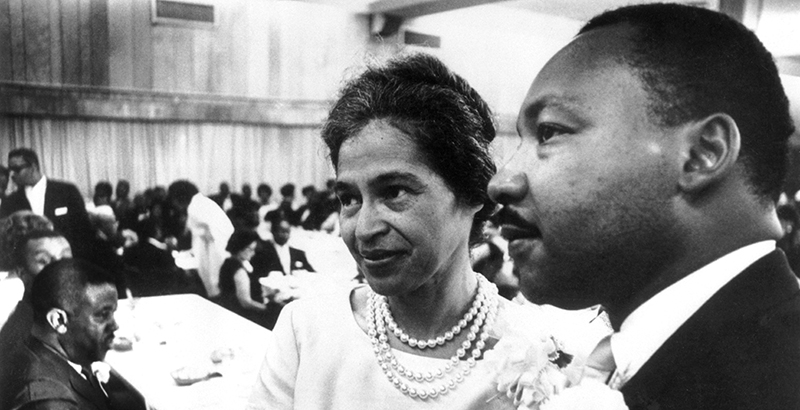

Many who advocate for education reform do so based on the notion that their pursuit is an extension of the work of civil rights advocates like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Many have called educational equity the civil rights issue of our time, and many have invoked the words and legacy of King and his contemporaries in making those declarations.

Today’s 50th anniversary of King’s assassination provides an appropriate moment for those of us who seek to pursue educational equity in his name to reintroduce ourselves to King, his life and legacy, and what that legacy means for our work today.

First, for King, education wasn’t a civil rights issue — civil rights was a civil rights issue, and that meant the fight against white supremacy was paramount.

For King, education — alongside issues of voting rights, economic opportunity, public accommodations, criminal punishment, and myriad other ways in which racism constrained the opportunities available to black people — was merely a symptom of the disease: the underlying white supremacy that generated racial inequities across a range of policy domains.

Those who seek to pursue educational equity in King’s name must be unapologetic fighters against the foundational white supremacy that breeds educational inequity. King’s dream was not one in which every child went to a school that enabled him or her to graduate on time with a college or career-ready credential; his dream was of a country in which the toxic stain of white supremacy had been eradicated so that young and old could live their lives fully and completely, beyond the limitations of the individualized and social dysfunctions wrought by white supremacy.

Education freedom fighters who seek to walk in the legacy of King must be passionate, vocal, and untiring opponents of white supremacy wherever it rears its head in order to embody King’s legacy.

Second, to pursue equity in a Kingian way requires a commitment to sacrifice, and even suffering. This principle is connected inextricably to the first — it is not possible to fight against white supremacy boldly, especially for people of color, if one is unwilling to suffer.

Precisely because he was fighting against the foundational underpinnings of white supremacy, and what that has meant to the ways in which resources and opportunities have been distributed in this country, King’s life was constantly in danger during the almost 13 years of his public work.

Mere weeks after launching the Montgomery Bus Boycott, King’s house, with his wife and daughter inside, was firebombed; he’d be jailed countless times; he’d be stabbed in the chest, inches from his heart; he’d be under federal surveillance for years; he’d be under constant personal attack from virtually all quarters; and he’d live most of his last decade under constant threat of death.

And, what’s more, he knew the moment he accepted E.D. Nixon’s call in November 1955 to lead the Montgomery boycott that he was signing up for a life precisely of this sort. The South left little doubt about what happened to those who dared to challenge white supremacy (Emmett Till, one of many of thousands of black folk lynched for even banal challenges to white supremacist thought, had been murdered only a few months prior to Nixon’s request.)

The legacy of King thus requires those of us who pursue educational equity in his name to do so boldly and to be willing to suffer severe consequences and reprisals. In fact, the absence of suffering, through the lens of King, is likely evidence of a lukewarm commitment to equity and thus a capitulation to white supremacist assumptions about resource and opportunity distribution.

So these, for me, are the foundational principles upon which the legacy of King rests. King’s legacy is broader, deeper, and larger than the more discrete questions that characterize many of our education policy debates today.

King, I suspect, would be quite vocal in condemning public schools that fail students of color generation after generation, and yet he also would likely be in jail right now after protesting the killing of another unarmed young black man by the police.

King, I suspect, would be quite vocal in advocating for children of color to be taught on the basis of globally aligned standards to ensure they can compete with anyone on the planet, and yet he would also be leading a protest against the deportation of Dreamers whose dreams are largely the same as King’s.

And King, I suspect, would be quite vocal in supporting any quality public school option that effectively educated children, and yet he would also challenge the priorities of federal and state authorities who seek to disinvest in the families and communities where these children reside.

King was a king because he had a commitment to justice and equity that few of us, if any, can match.

Very few of us are willing to pursue justice so boldly, and even fewer are willing to sacrifice our lives in that pursuit. We have children, families, mortgages, responsibilities, and most of us are much more practical — we’re content, if not happy, with incremental change, much more willing to take baby steps on the road to justice if it means we can maintain just enough support from the institutional authorities that shape our lives to hold onto whatever position we occupy (in our jobs, in our families, in our communities, or whatever the case may be).

Of course, King had practical concerns, too, but he is an icon, a hero, one of the great human beings of the 20th century, because he embodied the best of the human spirit — despite his flaws, despite his love for his family and children, despite his desire to be (“like anybody, I’d like to have a long life”), he was willing to sacrifice it all, his very life, for the rest of us, and ultimately for the redemption of our country.

Shavar Jeffries is the president of Democrats for Education Reform.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)