‘I’ve Been Having Nightmares…About Getting Shot’: Inside NYC March for Our Lives

Students, activists, teachers on why they marched for stricter gun legislation on Saturday

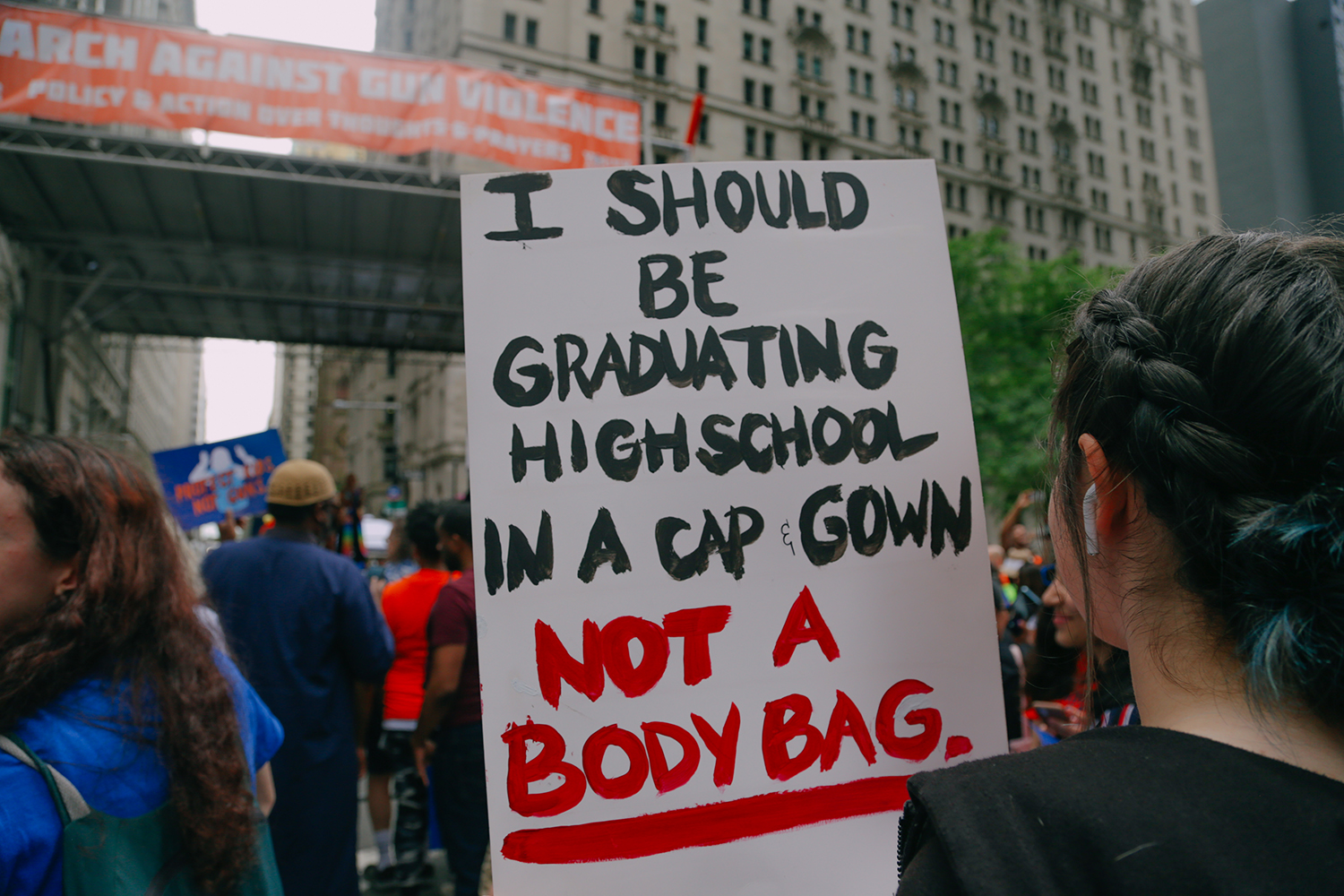

By Marianna McMurdock | June 13, 2022With faces marked by grief, anger and pain, thousands marched across the Brooklyn Bridge in protest of gun violence on Saturday afternoon.

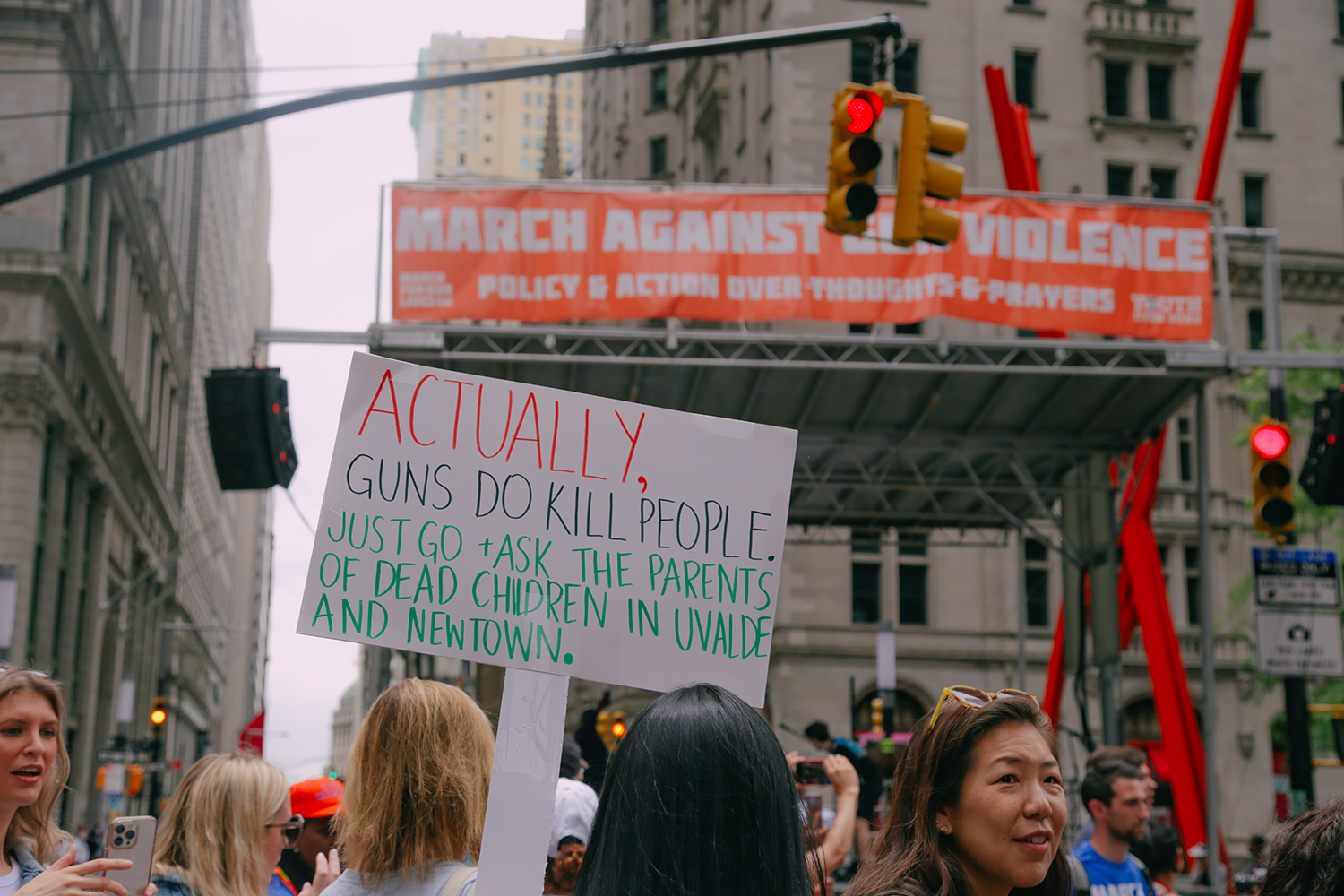

One of more than 450 local marches on June 11 organized by young activists and survivors, the second-ever March for Our Lives brought New Yorkers together to mourn and advocate for stricter gun laws in the wake of fatal mass shootings in Uvalde, Buffalo and Tulsa.

“The fact that we have to beg, scream and fight to not die while learning, shopping for groceries or praying is representative of a system that has failed us all as the American people,” said Felix Tager, head organizer for New York City’s rally, as he addressed a crowd arriving at Broadway and Liberty streets in lower Manhattan, which spanned at least seven blocks.

The organization, founded by student survivors of the 2018 Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, is advocating for universal background checks, red flag laws and for the legal age to purchase assault rifles to be raised to 21.

More than 70 bipartisan meetings were held by March for Our Lives youth activists in the week leading up to the June 11 marches, according to a press release. Many are cautiously optimistic for federal policy change after 10 Republican senators confirmed support for the legislation Sunday.

“Now we know there’s a more deafening sound than children screaming. Even more horrific than automatic rifles going off on a Tuesday morning. It is your inaction in the face of a looming gun violence epidemic,” said Luis Hernandez, founder of the advocacy group Youth Over Guns, who partnered with March for Our Lives and the United Federation of Teachers to organize the march.

“Mr. President, leave the tweeting to us and pick up your pen and sign executive orders until your fingers run numb,” Hernandez added.

Surrounded by financial headquarters in lower Manhattan, lead organizer Tager also advocated for banks like Chase and Citi to refuse transactions for military-style weapons, as Apple Pay has.

“This movement did not start with us and it certainly will not end with us. But one thing is clear. This time is different. It has to be different,” Tager said.

The 74 spent the day with the children, parents, activists, survivors and teachers marching for their lives. Here are some of their stories:

Hugo Cherry

Hugo Cherry is 9 years old, the same age as many of the children murdered at Robb Elementary in Uvalde.

“I wanted to go [to the march] because since before 2022 started I’ve been having nightmares, most of them are about me getting shot,” said Hugo, who lives in Washington Heights.

Being at the march in person did not make him less scared, Hugo said, though his older brother Odin, 11, was more optimistic and could imagine a day when “stuff like this won’t be a problem.”

“We shouldn’t even be doing those [lockdowns] in the first place… Because like weapons are being mass produced and they should probably only be used for war and even then, war shouldn’t be happening. Giving them to the general public doesn’t make sense,” Odin reflected.

Ayesha Khan

At 19, holding a sign that reads ‘the only thing easier to buy than guns are our politicians’, Ayesha Khan is tired. She remembers hearing news about Parkland and attending the 2018 March as a 15 year old.

Last November, after four students were murdered at Oxford High School in Michigan, she questioned her brother at the dinner table: “Do you have lock downs at your school? What do you do? Are you being smart about this?”

“It’s an unfortunate thing, but it’s something that you have to talk about [with] people that you care about… because it’s become a part of our life living in America.”

“When something like this happens and you just feel all this rage and just exhaustion and tiredness — there’s a lot of emotion,” said Khan, who lives with her family in Queens. “You’re just like a mess of a person at night when you finally close the news and you’re going to bed.”

She came to the march clad with face paint on a cloudy morning in June to feel less alone — surrounded by people fighting for change, just as “appalled” as she is.

Vaishali Subash

“This event is so important because it seems no matter how much people are shedding tears, blood is shed, people are dying… There’s so much power in numbers and that’s what we’re here to show today,” Subash, an organizer with March for Our Lives, told The 74.

“It’s almost unbelievable because most of the time we see a lot of activism through social media and those numbers are just not able to be visualized as easily, however, when we’re here in person seeing this, you can see every single face of someone who was personally affected by this issue.”

Sadie Tribe

Sadie Tribe, 14, vaguely remembers the Sandy Hook shooting but couldn’t process the situation because she was a toddler at the time. When a friend revealed she knew someone who recently died in a mass shooting, Tribe said the violent reality “hit close to home.” She decided to march and talk about gun reform freely at school.

“I wanted to come out here because students like me are the face of the movement and they have to be, and this is the only way to get the people in Congress to pass legislation that will save my life and the lives of people my age,” said Tribe, who lives in Manhattan.

Tribe’s older sister is now a senior at a Bronx high school. Her two-hour commute on the subway frightens Tribe.

“I’m really scared for her because shootings are taking place on trains as well as in school,” she said, “so her whole day is really threatened by this.”

Mariam Quraishi

Mariam Quraishi, 19, is a self-described cynic.

“I just think it’s exhausting. Because why are other countries looking at our country and making policies on gun laws, but we can’t do the same? … I think it says a lot that the rest of the world is willing to learn from our mistakes, but we can’t learn from our own mistakes,” she said.

“It feels like we’ve done this so many times… Like what kind of momentum does it take to bring actual change? Because we’re all here.”

Bayley Tuch

“I’m definitely one of those teachers who has always thought about, ‘Can these classroom walls protect me and my students from gunshots?’” said Bayley Tuch, a 7th grade math teacher at a Harlem charter school.

Tuch organized peers for the first March for Our Lives as a then-college student in 2018. The reality of school shootings did not affect her decision of whether or not to begin a career in the classroom.

“Most of my students are Black, so the conversation related to Buffalo got them really angry about the violence,” said Tuch. “They’re seeing this world and the racism that is coming out through gun violence, and then as students they also were scared and confused.”

Mia Tuttavilla

“I think about being a child and how afraid I would be — I didn’t go through this as a kid. I had fears of being kidnapped as a child because I remembered the Charles Manson story. This would have terrified me,” Tuttavilla told The 74.

She decided a week ago to organize her chosen family – friends and their children – to march in person.

“It makes us feel some sort of comfort, and I needed that comfort.”

Ekaterina Bomba

“I’ve been to many marches as a kid. I don’t remember most of them, but it does feel very different from them,” said Ekaterina Bomba, 12, who was surprised by the breadth of scheduled speakers and attended at the urging of their mother.

Bomba left the march thinking about the fear survivors shared.

“Like it is going to be my last moment — that was what really stuck to me, that feeling.”

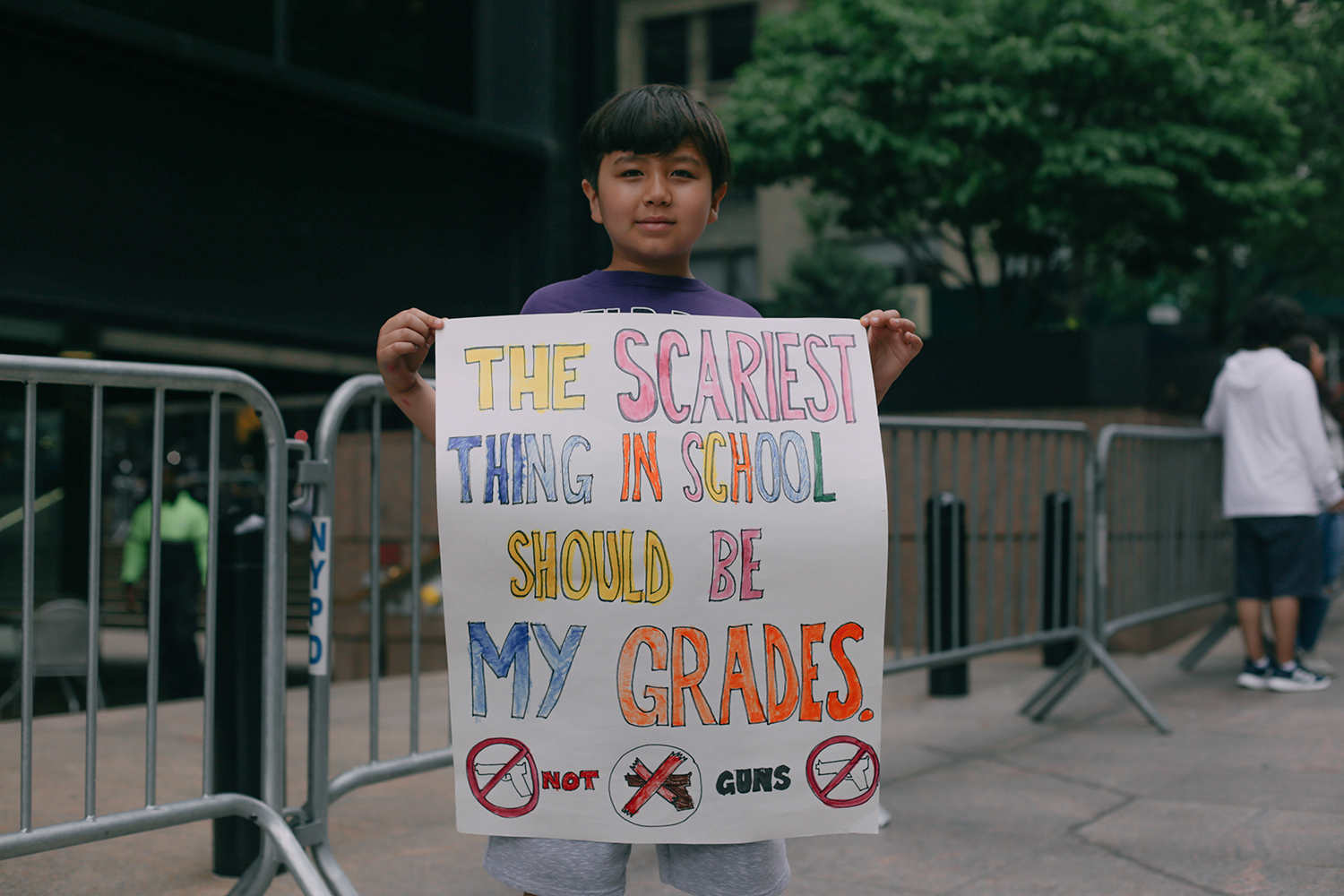

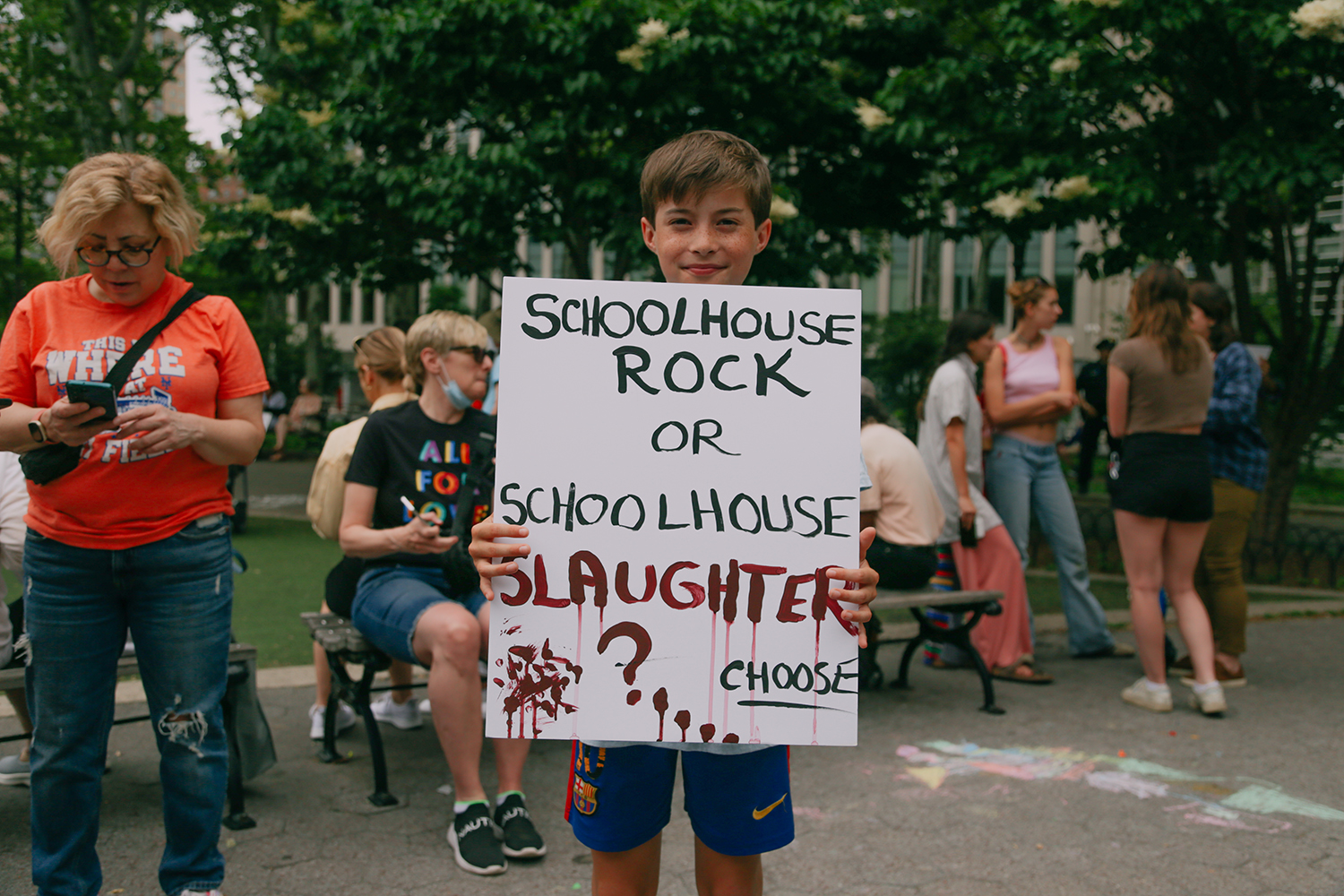

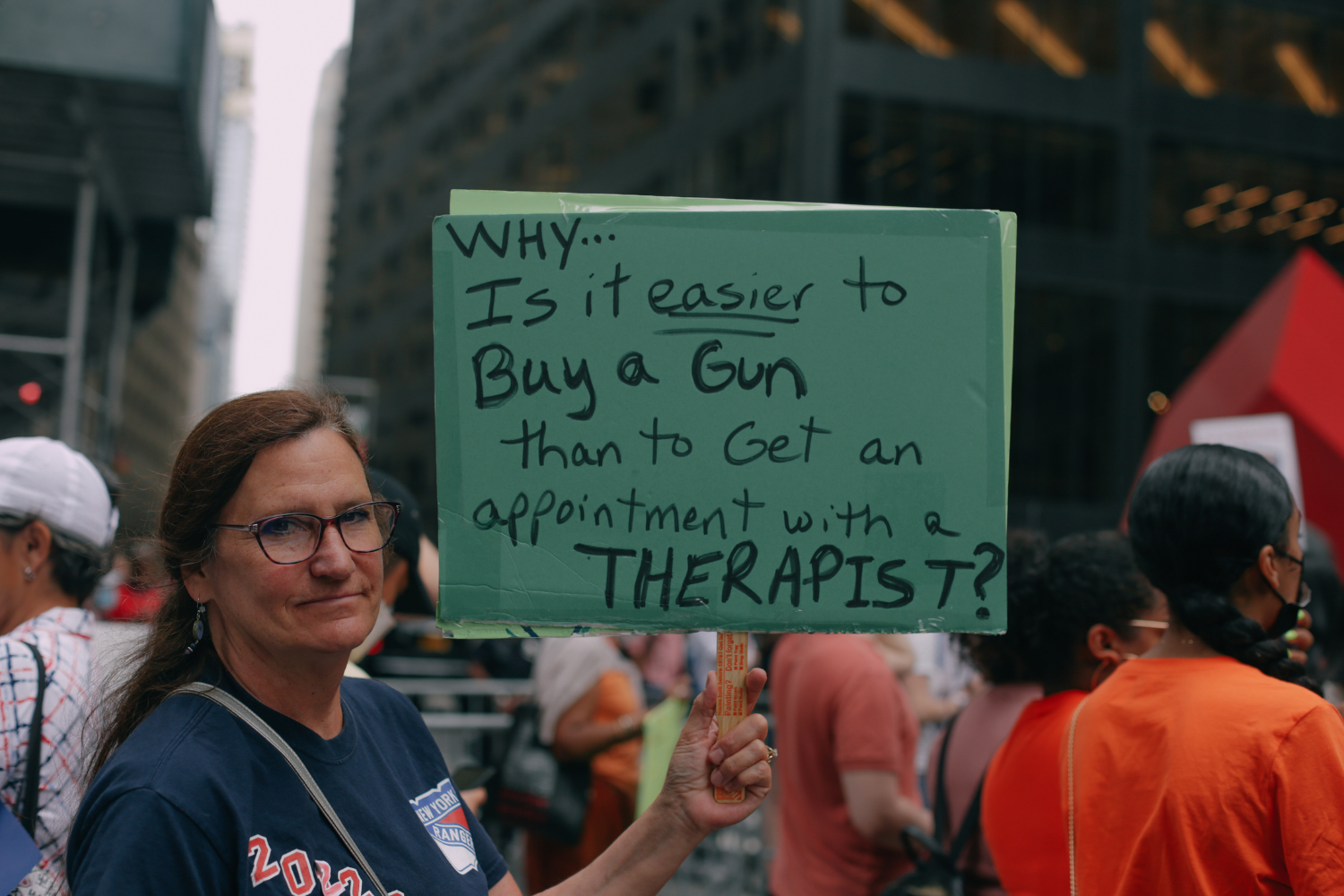

Below, see more scenes from Saturday’s March.

All images by Marianna McMurdock for The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter