‘It Gave Us a Choice When We Didn’t Have One’: Private School Choice Participants Flood Capitol to Tell Their Stories

Private school choice was among the only education pledges made by President Donald Trump on the campaign trail and has been a decades-long focus of advocacy by Education Secretary Betsy DeVos.

Congress reauthorized the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship, the only federally funded program, earlier this year, but like other Trump administration priorities, the odds of any kind of national private school choice program being enacted are looking increasingly slim.

The administration proposed a $250 million voucher program in this year’s budget; House Republicans, the caucus that should be most open to the idea, didn’t include the program in its 2018 Education Department spending bill.

There’s also been discussion of including a federal tax credit scholarship in a larger tax reform package, although the lingering health care debate has hampered legislative momentum on taxes, and a split among Republicans might sidetrack its inclusion anyway.

(The 74: Will the Same Conservative Coalition That Derailed Health Care Bill Now Kill Federal School Choice?)

At that somewhat pessimistic political moment, a group of students, parents, and alumni of school choice programs from around the country came to Washington, D.C., to share their experiences with press, lawmakers, and congressional staff. The American Federation for Children, the private school choice advocacy group founded by DeVos, organized the visits.

Here’s a snapshot of their stories:

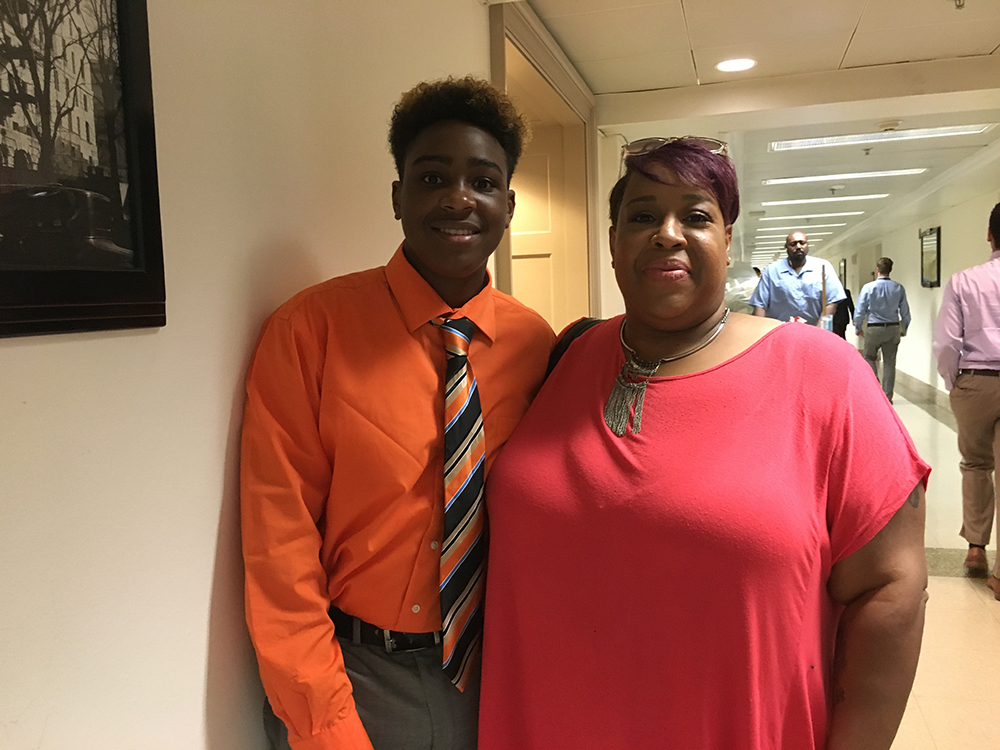

Charlanda and Amoreé Brown, Goldsboro, North Carolina

All of the public schools, from elementary through high school, in the Browns’ district were failing, and many were unsafe, Charlanda Brown said.

A Google search led her to a private school choice program. Her son, Amoreé, just finished eighth grade at a private school, his third year there.

“It gave us a choice when we didn’t have one,” Charlanda Brown said.

The private school removed the distractions Amoreé faced in public school, he said. Though just entering his freshman year, he has his eye on East Carolina University, with a major in architecture or occupational therapy.

He took the SAT last year and got scores high enough to be accepted into college, Charlanda Brown said, adding that she’s confident he’ll be successful in a few years when he enrolls.

Brown “isn’t a public school basher,” she said. Her mother works as a school social worker and her brother as a high school assistant principal. They’re more concerned with making sure students’ basic needs, like food, are met, and that schools are safe, and often can’t work on improving academics, she said.

“I agree that we need to fix [the public schools]. But he’s in the ninth grade. I don’t have time to wait,” she said.

Bertha Castaneda Guzman, Washington, D.C.

Castaneda Guzman attended a D.C. public elementary school, which was fine, but her parents were concerned about later years, she said.

She went to two middle schools — one Catholic and one, which later closed, with an international focus — before winding up at Archbishop Carroll High School.

Teachers there challenged her and made it clear there were options beyond high school, she said, while her peers who stayed in public schools lagged.

“Whenever we did talk about school, I’d be like, ‘Oh, what are you learning?’ And then the things that they were learning, I felt was like three years behind compared to what I was learning,” she said.

Archbishop Carroll also kept her out of the gang and drug violence that plagued her neighborhood, she said.

She went to Penn State University, where she was chosen for homecoming court — no small feat on a campus of 46,000.

Castaneda Guzman graduated from Penn State in December and now works as a technology consultant in Philadelphia. She’s also involved in beauty pageants and hopes to become the next Miss Pennsylvania.

Though she didn’t do any lobbying, she’d make sure legislators know that school choice empowers children as well as parents, she said.

“When you’re in elementary and middle school, you don’t really think about your future, but once you hit high school, there’s a time that you’re just like, ‘Wow, I’m kind of the navigator of my boat … Do I want to be a statistic, like from my neighborhood … or do I kind of want to overcome those obstacles and make my own destiny?’ ”

Kenya Green, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Green was raised for much of her childhood by her grandmother and aunts. She attended the same schools as a same-aged cousin, who had behavior problems, which meant frequent transfers for both of them. Those public schools were mostly poor, she said.

“They weren’t really any help to us. We were just there to be there, because we had to go to school,” she said.

Green didn’t pass the entrance exam for Milwaukee’s elite high schools, but a presentation by Hope Christian High School spurred her interest in eighth grade, and she enrolled there with a voucher for high school.

At Hope Christian, rigorous classes and caring teachers helped her raise her grades. She was on the honor roll for four years and graduated near the top of the class.

Her graduating class exceeded national and state averages for African Americans on the ACT, and 100 percent were accepted to college. The choice program allowed them to break stereotypes, she said.

She’ll be a junior at Wisconsin Lutheran College this fall, studying communications.

Green’s misbehaving cousin also wound up at Hope Christian, she said, eventually earning the “most improved” award, and is now in college as well.

The American education system lets five numbers — a child’s ZIP code — define who they’ll become, Green said.

“Everybody deserves a choice in what type of education they receive,” she said.

Gary Jones, Washington, D.C.

Jones and his wife Stacy have five children who have had experience with two different iterations of Washington, D.C.’s private school choice programs, he told The 74 earlier this year before the OSP program was reauthorized.

His three older children — Joshua, Aaliyah, and Yasmine — got scholarships and attended Catholic middle schools before an older version of the program folded, and they ended up back in D.C. public schools.

His two youngest daughters attended a DCPS elementary school they loved, but their zoned middle schools weren’t acceptable options, he said.

The older of those two daughters, Sabirah, got a scholarship to St. Thomas More, a Catholic middle school. There was no sibling preference, so their youngest, Tiffany, stayed at the local public elementary school, before Jones and his wife did whatever they had to in order to pay the tuition for private middle school.

“We struggled. I took out payday loans. I borrowed from my 401(k). I’ve done that for like three years now,” Gary Jones said.

The program now allows sibling preference, and Tiffany will have a scholarship for next year. Sabirah is now enrolled at Archbishop Carroll High School.

Joshua, his oldest, now works as a massage therapist in Los Angeles, and Yasmine is in nursing school. Aaliyah has a child and is figuring out what she wants to do, he said. Sabirah wants to be an entrepreneur in fashion and cosmetics, and Tiffany wants to be an astronaut.

“It’s not that we’re against public education,” Jones said, adding that his mother was a teacher.

And DCPS schools have improved, but slowly, he said.

“DCPS has made positive gains over the last, I’d say five, six years in reading and math, which is good,” he said. “But look how long it’s taken for them to get to this point.”

Jones has little patience for politicians who send their own children to private school but don’t want to provide the same choice to other families.

“Why are you making decisions for taxpaying parents, when your students don’t attend public schools? Why are you limiting our choices, when you have the freedom of choice to send your kids to the very best schools?”

Samantha Jones, Tucson, Arizona

Jones’s father was in the military, so she moved frequently as a young child, a trend that continued even after her parents divorced. She attended four elementary schools by the time she was in third grade.

“Public schools might work for some people, but they didn’t really stimulate me,” she said. She was gifted, she said, but the enrichment classes offered weren’t enough.

Through a school choice program in Arizona, she ended up at a Christian school starting in middle school. It was tough at first, but she got used to the rigor and said she was eventually accepted into 10 colleges and awarded over $500,000 in scholarships.

She’s now a junior at Northern Arizona University studying art education. Her three younger sisters used school choice programs, too, and a private option was able to help her youngest sister progress out of special education.

“Education is not about political affiliations. It’s a bipartisan issue. School choice is about opportunity for everyone, every child,” she said. “It shouldn’t matter your social class, where you live, what your family circumstances are that affect what education opportunities you have and affect your future.”

Jeneffer Lopez, Washington, D.C.

Lopez is the eldest of three children raised by a single mother from Ecuador who didn’t have the opportunity to complete school herself.

She attended D.C. public schools through sixth grade and was one of the earliest students to receive a scholarship after her mom saw an ad for the program on a bus.

Lopez attended Catholic middle and high schools. The schools were more demanding than those attended by her friends who stayed in public schools, and teachers and administrators took an interest in her outside school, including celebrating her win as Miss District of Columbia Teen USA.

It also kept her away from peer pressure surrounding drugs and alcohol, she said.

After graduation from Archbishop Carroll, Lopez completed degrees in business and economics at Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmitsburg, Maryland. She now works for Serving Our Children, the nonprofit organization that administers the OSP program.

She works mostly in the finance department but also helps applicant families, particularly those who speak Spanish.

Sharing her own story “gives the parents hope to know that the scholarship does work. They can see a bright future for their own students,” she said.

Her siblings also used the program and graduated from Archbishop Carroll. Her sister has since gone on to graduate from Penn State; her brother just completed his freshman year at West Virginia University. Lopez, too, hopes to go back to school to get a master’s degree in business and own her own business eventually.

Dominique Lyn and Braylen Grady, Cary, North Carolina

Lyn’s daughter Gabrielle was “struggling with acceptance and finding her way in learning” in her first three years at the local public school. With the help of a school choice program, Lyn enrolled Gabrielle in a private Christian school, where she’s now making the honor roll.

Son Braylen Grady was also having difficulties as a young child, so Lyn enrolled him in a private school for kindergarten, where he now looks forward to going to school and sometimes even wants to go on weekends, she said.

Braylen, who came to D.C. to lobby with his mom, likes playing with his friends, plus math and cursive writing, he said.

Tera and Sam Myers, Mansfield, Ohio

Tera Myers’s son Samuel, who has Down syndrome, started in public school but was bullied and wasn’t being well served, she said. She pulled Sam and his sister out of public school and enrolled them in a virtual charter school.

It was a good option at first, but eventually the coursework proved too challenging for Sam, and he wanted more social opportunities to be with peers.

In 2008, Myers started exploring options for Sam and his sister. There was a voucher program for students with autism, but that didn’t cover Sam. The family could afford tuition at a private school but not the costs of an aide and other additional supports Sam needed.

Legislators passed a special needs scholarship program twice, but then-Gov. Ted Strickland, a Democrat, vetoed it.

“We kind of just thought this is never going to happen in Sam’s lifetime to have choice in education, so we’ll just figure things out,” Myers said.

Republican John Kasich entered office in 2011, and he did sign a special needs scholarship program law. That was only the first hurdle; there wasn’t a local private school program that would meet Sam’s needs, so Myers, with the help of a special education teacher from the virtual school Sam attended, started one and ran it until last month.

The program runs through the Mansfield Christian School, and Myers ended up bringing together nine school districts in the county to support it.

“What I thought was going to be adversaries … ended up being a collaborative effort of all the schools working together,” she said.

Sam graduated in 2015 and now works at a local pizzeria, greeting customers and helping in the kitchen.

His favorite pizza to make is the “one with the little peppers.”

The Dick & Betsy DeVos Family Foundation provided funding to The 74 from 2014 to 2016. Campbell Brown serves on the boards of both The 74 and the American Federation for Children, which was formerly chaired by Betsy DeVos.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)