A bill being debated in Maryland in a committee that is chaired by an organizer for the state teachers union would give non-academic school measures the most weight they could possibly have in judging schools under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

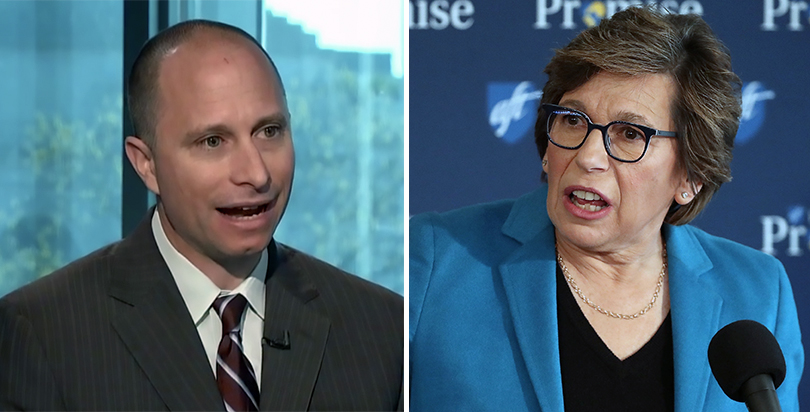

Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute, called out the bill Monday during a back-and-forth with Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, over measuring school performance and student learning.

“I know you’re hearing from the unions, the other educator groups, to minimize the amount that student achievement counts,” Petrilli said Monday to state superintendents assembled for the Council of Chief State School Officers conference. “Many of us, both people that come from the center-right, business groups, but also the civil rights groups on the left, worry about going back to the days when we are not being honest with the public and with parents about school performance.”

The Maryland bill that Petrilli cited would limit the combined total of academic indicators — particularly test scores — to no more than 51 percent of a school’s final rating. It would require at least three school quality indicators, like class size or the opportunities students have to enroll in advanced classes or career and technical education.

“In my mind, that is about sweeping under the rug the truth about whether students are performing,” Petrilli said.

Schools that are doing a “terrible job” and not educating kids could get a C instead of an F if they’re doing other things well, he said.

The Every Student Succeeds Act requires states to give “much greater weight” to academic measures but doesn’t specify how much or what the exact balance should be. Obama administration regulations to better define that meaning are moot after Congress passed a resolution blocking them, and the Trump administration has indicated that it will look to give states as much flexibility as possible.

The Maryland bill is sponsored by state Sen. Craig J. Zuker and is moving through a subcommittee chaired by state Sen. Paul G. Pinsky, who is also an organizer with an affiliate of the Maryland State Education Association.

Both Weingarten and Lily Eskelsen García, president of the National Education Association, the parent organization for the Maryland union, were on the panel with Petrilli. Garcia did not comment on the bill, though the moderator quickly moved to another topic, and the NEA did not immediately return a request for comment afterward.

Weingarten, who emphasized that she wasn’t speaking for the Maryland legislator or that state’s union, said the issue some states are grappling with isn’t how much weight to give academic indicators of school quality but how to judge student learning.

She suggested a capstone assessment, like those given to students in career and technical education programs, rather than English and math tests “which really didn’t work so well.” Capstone projects are long-term projects that challenge students’ higher-order thinking skills and that may result in a scientific study, in-depth research paper, arts performance, or some other culminating final presentation.

Unions have long complained one standardized test doesn’t give a full picture of a year’s worth of learning, and that the assessments aren’t aligned to what students are learning in class, particularly as states transitioned to the Common Core State Standards.

“Why can’t we have a capstone project as a requirement for every high school student and every junior high school student? That would be a far different and better way, I think, of assessing student achievement and student learning than a two-hour, three-hour test,” she said.

Petrilli said other measures are helpful, and he praised unions for finding new ways to measure student learning.

But “there’s a reason we ended up with standardized tests,” he said. Other measures can’t be compared across a state or provide data that can be broken down to show performance of English-language learners, students with disabilities, or other specific student subgroups that often struggle in school.

Weingarten said advocates shouldn’t correlate looking for new ways to measure learning with being opposed to measuring it.

“What I’m saying is that I think it was not right to … say that those of us who are learning and trying to figure out other, different ways, who are more aligned with what kids need to know and be able to do, that’s not the same as being anti–student learning,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)