Brooklyn, New York

“Take a deep breath in, take a deep breath out,” says AltSchool teacher Jenny Hartman as she kneels behind a table in her Brooklyn classroom, meeting a group of boisterous and boundary-testing young boys eye to eye. Temporarily subdued, the second and third graders return to drawing moon phases on a printed worksheet; in the background, other students gaze intently at laptops, headphones on.

“Tell me something you want to learn about the moon,” Hartman says, returning to the lesson.

The boys’ responses will shape what they study in the weeks to come.

“I already know what the moon is made out of — rocks and dust," says one boy.

“Could you ride a jet pack on the moon?” asks another.

Hartman translates out loud as she takes notes: “So we need to learn: What is gravity?”

Adaptive learning, personalized learning, individualized instruction: The idea that school experiences should be tailored to each student’s abilities and interests has taken root in Silicon Valley, with the backing of deep-pocketed philanthropists like Mark Zuckerberg, and is now spreading to cities outside the Bay Area bubble.

Some schools are dabbling in personalization via online curricula like Khan Academy; others are placing the approach at the core of their school model.

AltSchool sits at the forefront of this movement. Barely two years old, the school operator and education software company has already raised $133 million in funding. Research on personalization remains preliminary, but a report commissioned by the Gates Foundation points to the approach’s great potential. Over two years,

the study found, students engaged in personalized learning made “significantly greater” gains in math and reading versus their peers in comparable schools.

“There’s the potential for kids, if it’s used well, to learn a lot more than they used to,” Larry Miller, senior research fellow at the Center on Reinventing Public Education,

told Wired magazine.

Photos courtesy AltSchool

To hear AltSchool founder and CEO Max Ventilla tell it, scenes like the one above, recently observed at AltSchool’s newest location in New York City, will soon be replicated in classrooms across the country.

“Our mission is to empower all children to achieve their full potential — and that word ‘all’ is a big word there,” says Ventilla, a serial entrepreneur and firm believer in the power of network effects. From the company’s inception, his aim has been to serve students by the thousand, through a portfolio of owned and operated private schools and a larger network of education customers using AltSchool technology. “‘All’ requires you to think about how you can scale your impact, enabling other schools or school operators to transform the experience that they provide.”

That ambition to scale is what distinguishes AltSchool from the personalized learning of past generations. Wealthy families have always enjoyed personalization, to a degree, through tutoring, enrichment activities, and other opportunities that cater to their children’s abilities and interests. Ventilla, a father of two young children who previously ran personalization at Google, believes that technology can make those same opportunities affordable to all families, if the solutions are implemented in a radically reimagined classroom setting.

Ventilla took a first stab at redesigning classroom learning in 2013, opening AltSchool’s first micro-school in San Francisco’s Dogpath neighborhood. (The term “micro-school” has no formal definition, but it generally refers to a school with fewer than 150 students—a nod to Dunbar’s number—and looser age groupings.) Though the model has evolved, AltSchool Brooklyn looks remarkably similar, at its core, to the Dogpatch prototype. The pedagogical model is a modern, technology-supported spin on Montessori, with students learning together through interdisciplinary projects while mastering core knowledge and skills at their own pace, via a personalized sequence of digital curricula. Mornings are typically skill-based, with students progressing through structured online lessons in core subjects like math and reading. Later in the day students turn to planned activities and longer-term projects, with teachers playing a variety of roles—tutor, coach, community organizer—throughout.

For now, this experience comes at a high price. AltSchool charges tuition on par with that of tony, well-established private schools. In Brooklyn, the fee is $28,900 per year (some scholarships are available). But Ventilla, bent on growth and overwhelmed with parent demand, has been moving quickly to expand capacity. At the moment there are five AltSchool locations in the Bay Area, plus the Brooklyn outpost. By next fall, there will be three new locations in San Francisco, and one in Manhattan. And by fall 2017, there will be an AltSchool in Chicago’s Lincoln Park and a second Manhattan location.

"We’re in a place now where we could open more schools than we are,” Ventilla says, thanks to the millions of dollars AltSchool has raised to date. The timeline for the broader sale and distribution of AltSchool hardware and software, which would in theory further democratize the model, is less clear.

The company’s experience in Brooklyn suggests that parents in new markets will need to see AltSchool in action in order to believe in it. “When you’re in a new geography being high-touch is important,” says Zubin Canteenwalla, head of East Coast expansion and admissions. His team faced the challenge of recruiting Brooklyn families without having a local site up and running. In fact, slow construction forced the Brooklyn students and teachers to operate out of a temporary space in a nearby preschool until mid-October.

“I think people felt nervous about sharing their concerns about joining a first-year school. That’s okay, you can be cautious with your decisions,” says Canteenwalla, a startup veteran and father of two young children. “Now the onus is on that to show them that we’re living out what we said we would live out.”

Last September Canteenwalla’s team secured a second New York location, in Manhattan’s East Village, with a maximum capacity of 60 students. He anticipates that the space, which previously served another school, will be ready for tours far earlier in the admissions process. Plus, he says, prospective families will be able to tour the finished Brooklyn Heights school, further demystifying the AltSchool classroom experience.

That access will be particularly important for younger grades, where parents concerned about screen time might be encouraged to hear that the company is not parking four-year-olds in front of laptops. Quite the opposite: on a recent morning visit I found AltSchool teacher Mara Pauker sitting on a miniature chair at a miniature table, flanked by two of her pre-kindergarten students. The girls look intently at the items spread out in front of them: a colander, plastic knives, plump red tomatoes, and a mysterious green ingredient.

“Um, leaves?” a girl in a “Sparkle Star” t-shirt ventures, eyebrow raised.

“Give it a smell,” Pauker says.

The two girls lean in, and suddenly the table is crowded with a ring of classmates who have migrated from the building blocks zone near the window. We all take a deep whiff together.

“Basil!” another student squeals.

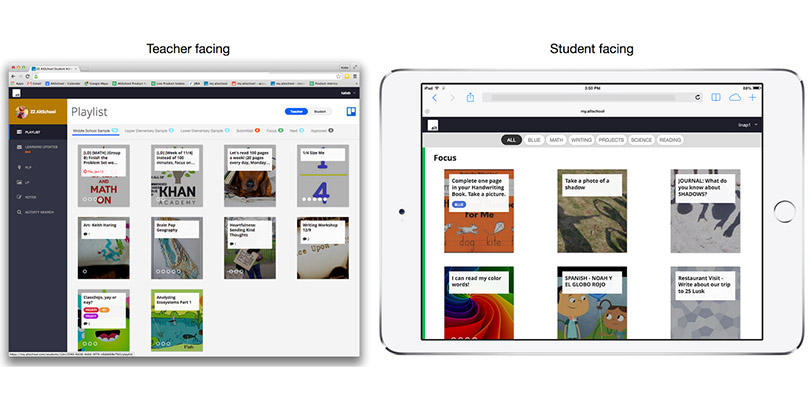

Pauker nods her approval and continues the recipe she’s been writing in large letters, rebus-style, on a piece of paper for all to see. “Wash the [basil],” the neat print reads, with a colored picture standing in for the herb. Then, as the students carefully snip basil with safety scissors and bisect grape tomatoes with plastic knives, Pauker takes out her laptop, logs in to her AltSchool account, opens a "new lesson" page, and connects the laptop to a large flat-screen on wheels that stands alongside the table.

“I need a new name for this one,” she tells the group.

“Pasta Delicious!” “Pasta Woo Woo!” the chorus replies.

An example of AltSchool technology, the teacher view vs. student view

Pauker asks the students to list the ingredients, and then the tools. After she creates the lesson, the platform automatically generates a checklist that other teachers interested in the same learning objectives will be able to follow.

The seamless workflow is a rare thing for teachers accustomed to juggling half a dozen apps and tools. AltSchool currently employs as many engineers as it does teachers, and their ability to collaborate seamlessly and nimbly has been the key to the company’s rapid product development.

“One of the benefits of having our users close to me is that we have a pulse on what’s happening,” Rena Barch, a user experience researcher with dark hair and hipster glasses, tells me as she takes a seat in the back of a Brooklyn classroom. Barch has walked from AltSchool’s nearby administrative offices to observe how teachers document student learning. By understanding their workflow, she and the engineering team, based on San Francisco, will be able to better design, and modify, teacher-facing tools in the AltSchool platform.

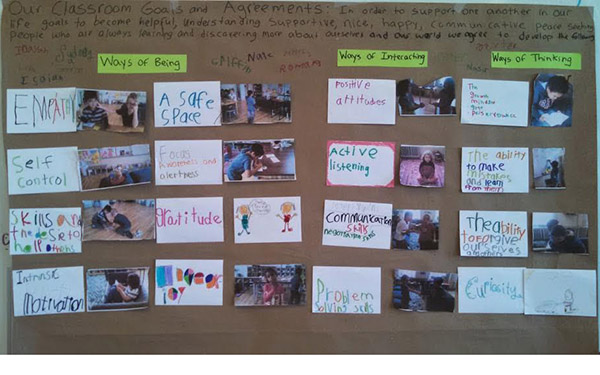

This push for continual experimentation, iteration and improvement extends beyond AltSchool’s engineers to its teachers and students as well. Down the hall, past a wall of colorful student drawings and coats neatly placed on hooks, I find Brooklyn head teacher Jamie Stewart. “We’re doing expert projects right now, drawing the kids into this model of owning a piece of what they do at school,” Stewart says. “We’re focusing on asking questions and developing resources and compiling those things to [help them] become an expert.”

Stewart worked in public schools for seven years before joining AltSchool. In Brooklyn, she has been focusing on tweaking the Bay Area model to suit an East Coast environment. “The neighborhood that each school is in has definitely informed what the students are interested in learning about,” she says. A walk along the East River sparked interest in scuba divers, boats, and helicopters. “That emergent thread wouldn’t happen in SF.”

The question remaining is whether parents in markets outside of the Bay Area will embrace AltSchool’s intentional break with elementary school norms and traditions. Last spring, at a parent information session held in the early evening at a DUMBO nonprofit, AltSchool staff members tried to engage families around the question, “What type of education will best prepare our children for the 21st century?” They dutifully explained AltSchool’s three central principles: personalized education; teacher empowerment; and partnership with parents. And they made the case for modern features like flexible drop-off and pick-up times, designed to better accommodate parents’ work schedules.

But the audience questions remained rooted in existing conceptions of school: “What are your admissions criteria?” “You have limited space — how will you do science labs and music?”And top of mind for one young girl, sitting in the front row: “If it’s raining, do we go outside for P.E.?”

AltSchool’s admissions requirements are perhaps the most inscrutable aspect of the model. “Our mission here is to create a great education for all students. That’s a very inclusive statement,” Canteenwalla says. “It’s not like we have some bar that we need students to clear in order to admit. It’s about creating balance in the classroom.”

To anxious private school parents accustomed to compiling letters of recommendation and hiring test prep tutors, that lack of a benchmark may prove stressful. Moreover, the veil of secrecy surrounding the process makes it difficult to assess how well AltSchool’s technology platform would perform in schools where the startup has no control over classroom composition. What happens when the teachers are less talented (last year 2,200 applicants vied for 20 available jobs) and the families can’t afford tuition north of $20,000? Investors like Learn Capital managing partner Ryan Hutter have noted that if AltSchool were to disrupt the private school market alone, worth $55 billion, the startup would still be wildly successful. But the company’s philanthropic investors, guardians of AltSchool’s far-reaching mission, might beg to differ.

The question of AltSchool’s mainstream appeal came into even sharper focus last week, when Ventilla announced AltSchool Open. For the first time, the startup will be making its software and services available to external schools, positioning the company to capture a second, and potentially larger, revenue stream.

“We want to partner with amazing people who are interested in opening and operating new schools supported by AltSchool’s platform,” Ventilla told the education insiders gathered in Austin at the South By Southwest Education conference. He also acknowledged the importance of diversity: “[our technology] must be informed by the experiences and perspectives of a broader base of educators and families than only within our private schools.”

The announcement is a first step toward fulfilling the promise of equity embedded in AltSchool’s founding aspirations. Ventilla, who incorporated AltSchool as a B-corp, quit his job at Google after losing patience with the elitism embedded in the private preschool admissions process. "There are very few other things where the quality of it is defined by the exclusivity of it, and I had a little bit of a knee-jerk reaction to that,” Ventilla told the curious attendees of a recent tour in Brooklyn, the edge in his tone a rare flicker of emotion from an otherwise subdued and deliberate speaker.

In the end, the students themselves will be gauge whether or not AltSchool achieves Ventilla’s heady goals. In Brooklyn, the early indicators are encouraging, if not conclusive. Stewart’s second and third graders convene twice a day, once in the morning and once in the afternoon. A “speaking stick” helps manage the discussions; to endorse a comment, students use the sign language for “love,” raising their hands.

“We start the year with a conversation: Why are we here? What should we do at a school?” she says. Stewart and Hartman take a back seat during the discussions. “It helps all kids feel involved.”

One day the class discussed how AltSchool compared to their prior school experiences. “At AltSchool they trick you into learning, but it really works,” one student said, Stewart recalls.

In response, a wave of small hands shot into the air, all making “love” signs.

;)