Indiana Officials Say Chronic Absenteeism Rates Improving, but More Work Ahead

Chronic absenteeism surged during the pandemic in Indiana, nearly doubling to peak at 21.1% in 2022.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Indiana’s top education officials applauded the state’s improved chronic absenteeism rates on Wednesday but conceded that too many Hoosier students are still missing a “significant” number of school days.

The latest attendance numbers released by the Indiana Department of Education reported that 17.8% of K-12 students — roughly 219,00 kids — were “chronically absent” during the most recent 2023-24 school year, meaning they missed at least 18 days.

It’s the second year in a row that the number of chronically absent students went down, dropping from 19.2% in 2023, and 21.1% in 2022.

“It’s an improvement — and we always want to celebrate improvements and data moving in the right direction— but we still have some work to do,” said John Keller, IDOE’s chief information officer, during Wednesday’s State Board of Education meeting.

Keller maintained that the reasons for absences vary, but “the interpretation of the ‘why’ is really going to have to be a locally determined thing.”

“Our general focus has been making sure that there are no insights in the data that remain unturned. But what we’re doing is holding up the mirror on this attendance data and allowing schools to slice it any way they can possibly think of,” Keller said. “I’m guessing there are probably different approaches that we use to address the most chronic of the chronic absenteeism, versus things that are maybe a little bit more episodic and not as much of a long-term pattern. But that’s what we’re trying to look at with broader analysis.”

Educators around the state have pointed to family challenges some students face at home, along with hard-to-break tendencies to keep kids home when even mildly unwell — a habit borne out of the pandemic — as key factors.

Schools are getting creative to try to combat the growing problem, like increasing communication with parents and incentivizing absence-prone students to come to class.

IDOE officials are also working on responses to improve school attendance, including development of a new “Attendance Insights” dashboard that breaks down weekly habitually truant and chronic absenteeism rates at the local and school levels. The state has already made the tool available to Hoosier school officials and plans to launch a public version later this month.

“It is statistically significant — students who are coming to school 94% of the time are doing better, significantly,” said Indiana Secretary of Education Katie Jenner. “As a parent or a grandparent or whatever, that 94% or more really, really matters. Teachers could have told us this before we ran the data, right? But running the data, it is very clear students need to be in the classroom in order to make the greatest performance.”

A deeper look at the data

Student absences have been on the rise since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indiana and across the nation. Chronic absenteeism surged during the pandemic, nearly doubling to peak at 21.1% in 2022, according to IDOE.

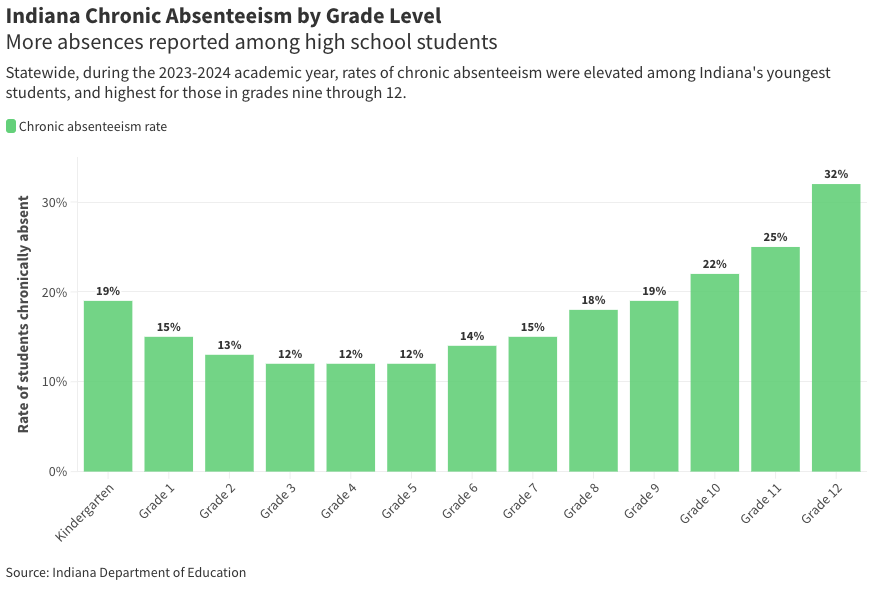

Keller said the latest data suggests Indiana has “turned the corner” and appears to be reversing from its high-absence period during the pandemic. He emphasized that all grades levels improved their chronic absenteeism rates in 2023-24 by one to two percent when compared to the year prior.

“These are not insignificant improvements,” Keller said. “But obviously, we have not returned to the pre-pandemic attendance.”

According to the 2023-24 data, 23.7% of students who receive free or reduced lunch were chronically absent — nearly 11% higher than their peers. English language learners were also slightly more likely to miss class; 18.5% of English learners were chronically absent during the last school year, compared to 17.7% of non-English language learners.

The Indiana Code specifically defines chronic absenteeism as being absent 18 or more days within a school year for any reason — a higher standard than “habitual truancy,” which is ten or more days without an excuse.

Under the “compulsory education” laws in Indiana, children must regularly attend school from the time they’re seven years old until they turn 18, with some exceptions.

But unless they’re excused, students who cut class too often could end up under a juvenile court’s supervision. Built-up absences could also prompt prosecutors to file misdemeanor charges against Hoosier parents, given that they are legally responsible for making sure their children go to school.

Keller took notice of “consistent, dramatic differences” in academic performance for students who are chronically absent versus those with better attendance.

“The data pretty much speaks for themselves. There are stark differences between the populations on all these measures,” he said, referring to “noticeably” lower scores on IREAD, ILEARN and the SAT among chronically absent students.

“No matter the quality of the interventions, it doesn’t matter so much if (students) are not in the room,” Keller continued.

IDOE officials further noted that students who are chronically absent are significantly less likely to read by third grade, master key ELA and math skills, or be college-ready.

“The magnitude of that is startling,” Jenner said. “We look at the high schools, which is certainly the most significant, but if you look at kindergarten and first grade — that is a lot higher than it should be. That’s when our teachers are working on the foundations with kids. So, we’ve got to make sure that habit is early, that kids are getting to school.”

New tools going live

At IDOE, Keller said state officials have “shifted” their focus from “just a school-focused look at attendance” to honing in on individual students.

“The old way of looking at attendance was adding up all the days kids could have attended school, looking at all the days they did attend, and then creating a rate out of that number,” Keller explained. “Now we’re looking at the student level and saying, ‘For this kid, did they attend 94% of the time they could have attended?’”

Other ongoing analyses at the state level are digging into patterns of chronic absenteeism.

“Are the students who are chronically absent in any grade this year, were they the prior and the prior and the prior and the prior years?” Keller questioned.

Data shows that in 2023-24, about half of the chronically absent students had been chronically absent in one of the last prior three years. “And half of them were new to the roster, if you will,” Keller said.

The new “Attendance Insights” dashboard — meant to help state and local officials investigate data trends — went live for school officials Aug. 23. A public version will be available later this month or early in October.

The dashboard shows several years worth of week-by-week attendance data — including excused and unexcused absences, as well as rates of chronic absenteeism and habitual truancy — for individual schools. Because schools already report their attendance numbers to IDOE, Keller said the dashboard will show the most up-to-date data.

Filters additionally allow users to break data down by students’ race, ethnicity and socioeconomic and English learner statuses.

“We want to set the table for schools to do that analysis, identify trends and patterns, areas where data collection can be improved,” Keller said. “We want to work with a variety of stakeholders to identify root causes.”

Board member Pat Mapes said the dashboard can help school and district administrators show parents “that difference between academic achievement and whether or not you’re at school.”

“Because it doesn’t matter how much the school sends letters, makes phone calls — parents have to understand that your kids in our buildings is how they can progress academically and build the skills they need to be successful,” Mapes said. “We’ve really never had anything like this to be able to pull data out to really make that story.”

Also in the works is an “early warning system” that studies more than a decade of data patterns among students who graduated high school — and those who did not graduate — to identify possible behaviors of concern and risk factors for becoming chronically absent.

Currently, the 11 Hoosier school corporations are participating in a two-month pilot.

“We want to get it out as soon as possible. We want to stop the trial, take away the placebo, and give everybody access,” Keller said. “But we’re not going to do it until we’re confident.”

Indiana Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Indiana Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Niki Kelly for questions: info@indianacapitalchronicle.com. Follow Indiana Capital Chronicle on Facebook and X.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)